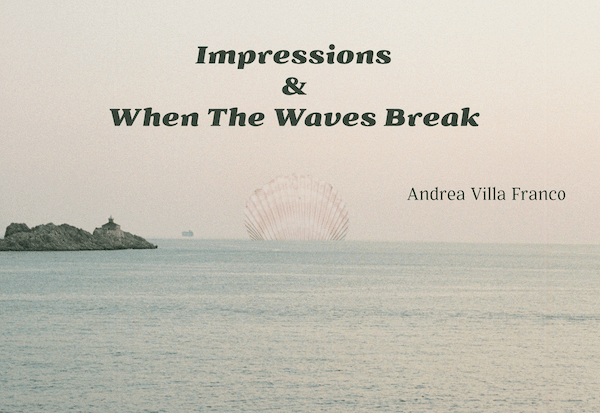

Impressions

The shell of a hermit crab lies among the dried leaves of the path that I followed into the woods. Hollow and brown, it blends into the loose soil, the leaves, the tree roots. Almost like a stone—but too polished, still bright, even in the gloom of the forest canopy.

Bending down, I trace, with my gaze, the thick spiraling curves of the shell that dissolve into shadow. Faded amber and white etch webbing onto the hard surface, like the bright and uneven speckling of a leaf hit by sunlight.

After an hour of uphill trek, the slope of the trail had just begun to level. At any moment, it should begin to dip. This steep hike leads to no notable viewpoints, no lakes, no waterfalls, just the shaded woods with cool temperatures, even at noon.

I wonder, rising up, at how the shell of a hermit crab came to cross my path, which has always been an inland path, high above sea level.

You once told me: Maybe that’s why the ocean sounds so calming, it sounds like someone breathing close to you.

I step past the shell of the hermit crab and follow the level trail deeper into the midday gloom. The path begins to stray east. Here, the shadows set in around me, and only the echo of my own breath reaches my ears.

I do not know the sea.

But by heart do I know every curve, every ridge that it has carved into mineral.

You used to spread them out on the bed, in the late afternoon, and group them into clusters on my white bedsheets, by shape, by geography.

Veneridae, textured color like impressionist paint, from Queensland.

Volutidae, glossy folds of cream-stained pink, from Patagonia.

Naticidae, thick spirals of amber and coffee, from the Caribbean. You brought the sea into my bedroom, and I had no say in it.

And now, I breathe, I see the bend ahead, the sharp twist of the trail down into steep descent.

This steep hike leads to no notable viewpoints, no lakes, no waterfalls—and yet, I came upon the shell of a hermit crab lying in my path, a path which is supposed to be an inland path, a path high above sea level.

And if I were to descend and emerge from the woods, would I see the blue horizon, the rocky outcroppings, the boats cradled by the waves that you so often described to me?

On those late afternoons, you brought them out, one by one, from brown paper bags and spread them out onto the bed. Shells from every shore on every continent, from islands so small that on maps, the blue pigment swallowed up the black specks adrift.

Shells that left behind soft dents on my white bedsheets.

When the Waves Break

Born inland, like me, my mother was cradled by mountain peaks and swaddled in thin high-altitude air. But, in the early light of cold weekend mornings, she liked to extract and examine the little fragments of the sea that, over the years, had become imbedded deep within her, like bits and pieces, buried in the sand, of a boat thought to be lost at sea.

Over a cup of black coffee, she evoked: the sway of the palm trees, campfires on a beach at dusk, the grains of sand that peppered the toasted coconut rice and the white flesh of the fresh fish that she tore to pieces with her teeth.

Anecdotes that I too learned by heart.

Red rocks, cacti, anchored boats, white sand, tin-roofed shacks seen from above, and the sea, unpeopled in the yellow haze of the sun and lost time.

I flip through the picture album that she kept in her nightstand. Past the photos of me, as a toddler dressed like a dolphin, as a baby in the arms of a stranger, and past her red cursive that sweeps by:

Monday, 1st of March 19—

Yesterday we went to—

This is the stray cat that—

The handwriting gives way to blank margins that frame pictures with edges softened by time. And yellowed by time or yellowed by the invisible sun that lights scenes of dusty boats huddled in a turquoise bay, seeking the crimson embrace of the bare rocky hills.

I flip through pictures and pictures of a horizon—split in two.

She used to tell me that she didn’t know why or how she had managed to take so many empty pictures, photos that made it feel like no one ever lived nor could ever live by the sea.

But at sea, my mother did learn to suck on the fatty fish brains that trickled down her chin and dripped onto the sand, pale and hot. She learned to jump off red rocky outcroppings, to dive into dark teal depths. She learned to allow the slimy sea grass to caress her feet, her calves, her thighs.

I flip through them, pictures and pictures of a powdery sky, the flat turquoise sea—as seen by a child who has just discovered the sea.

But at sea, my mother also learned of the blue indifference that sets in, quiet, after a current sweeps two bodies against a red rocky outcropping. After they fade into specks that float further and further—beyond the horizon, beyond reach.

On the last page of the picture album, a young couple smiles for the camera. He wraps his tanned arms around her small, bony frame. They lie, embraced by red rock, in a nook carved out by the waves that splash at their bare feet.

Andrea Villa Franco is an uprooted writer and freelance journalist from Bogotá, Colombia. Her nonfiction work has appeared in Americas Quarterly and Pie de Página. She currently works as a research fellow for the Human Rights Foundation.