The face of the revolution wears masks. Plastic masks with glittery swirls, Plague Doctor masks with the long Venetian beak-noses, spray painted all black. Bandanas tied over mouths like cowboys on a raid, tips of folded squares pointing down from chins like the beards of V for Vendetta crusaders. Undershirts painted with bold, passionate lines spelling words that demand to be noticed like streaks of lightning. Combat boots and nose rings and spiked mohawks, dyed hair in all of the colors of the rainbow, the Pride flag draped over shoulders like a cape.

The face of the revolution is being photographed by art students, is comprised of art students. I ran into a writer who I lived with in Prague, and she introduced me to her sister. “Oh you’re the acrobat!” I grinned, as my toes stuck through the wrought-iron rusted bars of the fence separating the protestors and the Chicago police force. In response, she took her left leg and lifted it straight off the ground and over her head effortlessly. When she smiled, the glitter that she had pasted to her cheekbones sparkled under the flickering streetlights.

The face of the revolution hangs on the street lights. A girl with a bandana tied over her face throws her black hood over her pulled back hair, muscular legs in tight black skinny jeans poised on the bottom of a streetlamp. She holds on with one arm, but uses her other hand to imitate the motion of fingering her vagina—pinky and forefinger extended straight out, like the inverted rock and roll hand gesture, middle and ring fingers folded back to reach for an imaginary clit. Her tongue snakes out of her mouth aggressively. ‘Pussies in Formation’ signs dot the sidewalk like seagulls in crowded parking lots.

They march peacefully, they stream between cars like water splitting over rocks in their path. The cars honk. Some people stand in their sunroofs, whooping and hollering. Back windows are rolled down, hands are extended, high fives are exchanged. Phones stick out of drivers’ side windows, peace signs out the passenger sides. People lean forward out of their seats, feeling empowered by the emotion of the stormy rallied forces. Whose streets? Our streets! they shout. They weave through traffic on Lakeshore Drive, over the river itself, stranded on the overpass with the blue eye of the Navy Pier ferris wheel winking in unison with the flashing blue and red lights of cop cars, silhouetting forms like shadow puppets.

The face of the revolution climbs on the top of CTA buses as the drivers still sit in the front seat, hands in their pockets, grins on their faces. The kids on top raise their skateboards high, painted with “Fuck Trump” between their wheels to match the messily scrawled “Fuck Trump” in red paint that slices across the side of the bus.

•

On November ninth I woke up in a world where the air felt heavier. Reality felt seized in a bizarre chokehold, time seemed weighted by the gravitational pull of a thousand anvils. I lay on my twin-sized mattress, no bed frame, in my South Loop apartment, listening to the ‘L’ train rattle past my window. I imagined the thoughts of each person on the train, commuting tirelessly to work, going on about their day. Normality felt stalled and yet the ‘L’ was running seamlessly. Did its passengers feel disquieted, unsettled by recent events? Did they feel the subtle push of this new reality beginning to slowly fray the delicate threads of progress, the spider-silk safety net that we had so carefully crafted? Could they feel it unraveling into chaotic coils right before their very eyes? No safety net. Teetering on high-line click-clacking train tracks, tight-roping like the ‘L’. Free-falling.

•

Glass shatters like a bowling ball strike against the concrete, covered in angry red scrawls of still wet spray paint that glisten in the glow of phone flashlights. The heads of the people standing on the perimeter of the crowd swivel to the source of the noise. A single figure stands on the concrete ledge above the steps to the riverwalk. “Oh shit. Guys, that was an accident I swear. This is a peaceful protest!” The man in his early twenties steps gingerly down from the concrete ledge, his short legs plopping awkwardly onto the ground only a few feet below, avoiding the shards of glass that glisten like dew. The water of his San Pellegrino sprays outward like the tape-outline shadow at a closed crime scene. “I don’t know what to do…” He kneels down and pinches the shards between his fingers. “I’m gonna clean this up…”

•

I moved to Chicago from my parents’ house in Detroit. There I had lived in a neighborhood where we cultivated small gardens disguised as boulevards and street beautification but really those dividers were built to keep out those who lived outside our borders, those who congregated at the bus stop next to the abandoned Michigan State Fair grounds.

My ex-boyfriend at the time called the neighborhood he lived in “The Asshole of West Bloomfield” but he lived across from a golf course. I lived next to a cemetery, across from the abandoned State Fair grounds and a newly established medical marijuana shop with blinking neon green lights. My neighborhood was primarily black, yet segregated nonetheless on the basis of class privilege.

•

I watch as we pour out onto the metal stairs leading up to the ‘L’, banners and excited limbs flailing over fences to wave at the stream of people trailing below. One hanging banner reads in big, black, unignorable paint: “The face of my abuser is now the face of our country”.

Long-boarders and skateboarders run circles around us and a boy with a short bike hoists its frame above his head in front of two cop cars blocking the road like a V. His friend’s long lens points at him and clicks excitedly. I recognize friends from Columbia and my friend recognizes groups from SAIC atop the multiple buses that litter the stopped traffic.

I look at one of the few cops standing near the far side fence before the Trump Tower. He stands with his hands shoved underneath his thick bulletproof vest. Each pocket houses a different weapon: a gun, a taser, tear gas. A wooden baton hangs from his belt and occasionally when the noise gets too loud on the front lines, he turns his head nervously, hand instinctually reaching towards the baton.

I think of my dad wielding his wooden nunchucks in our house back in Detroit, showing me what he would do in the case of a home invasion. The nunchucks usually rest over the golden knob of a door to the kitchen that always stays open, so they’re out of sight against a white wall. My dad swings the nunchucks wildly in the air, and one of the wooden clubbed ends whacks him against the back. “Fuck. Ow.”

The cop looks like the lazy guy from that stupid TV show with Zooey Deschannel. My palms are rusted brown from gripping the wrought iron fence but I pull myself up and bend over the fence’s sharp edges to stare down the men in blue.

“Who are you protecting?” I shout. He’s only a few feet away from me.

He meets my eyes for a moment. He pouts his lower lip and shrugs.

•

I walked down Wabash on my way to class the morning of November ninth. Every person I passed, I imagined in silhouettes of red or blue or gray, their mouths sewn shut, voices rusty and metallic with disuse, devoid of depth, devoid of empathy. Who had the privilege of supporting a businessman whose bigotry was not their issue? Who supported a candidate who promised to build a fence to keep the outsiders out?

I watched a black man in a neat grey business suit unlock the door to his apartment and wondered what the future held for him. A chubby and ruddy-cheeked toddler with glistening blue eyes stuck his tongue out at me on the crosswalk. He began to waddle in my direction. I wondered about the implications of his upbringing, what it would be like to grow up in a country that was okay with electing a racist, a xenophobe, an accused rapist?

•

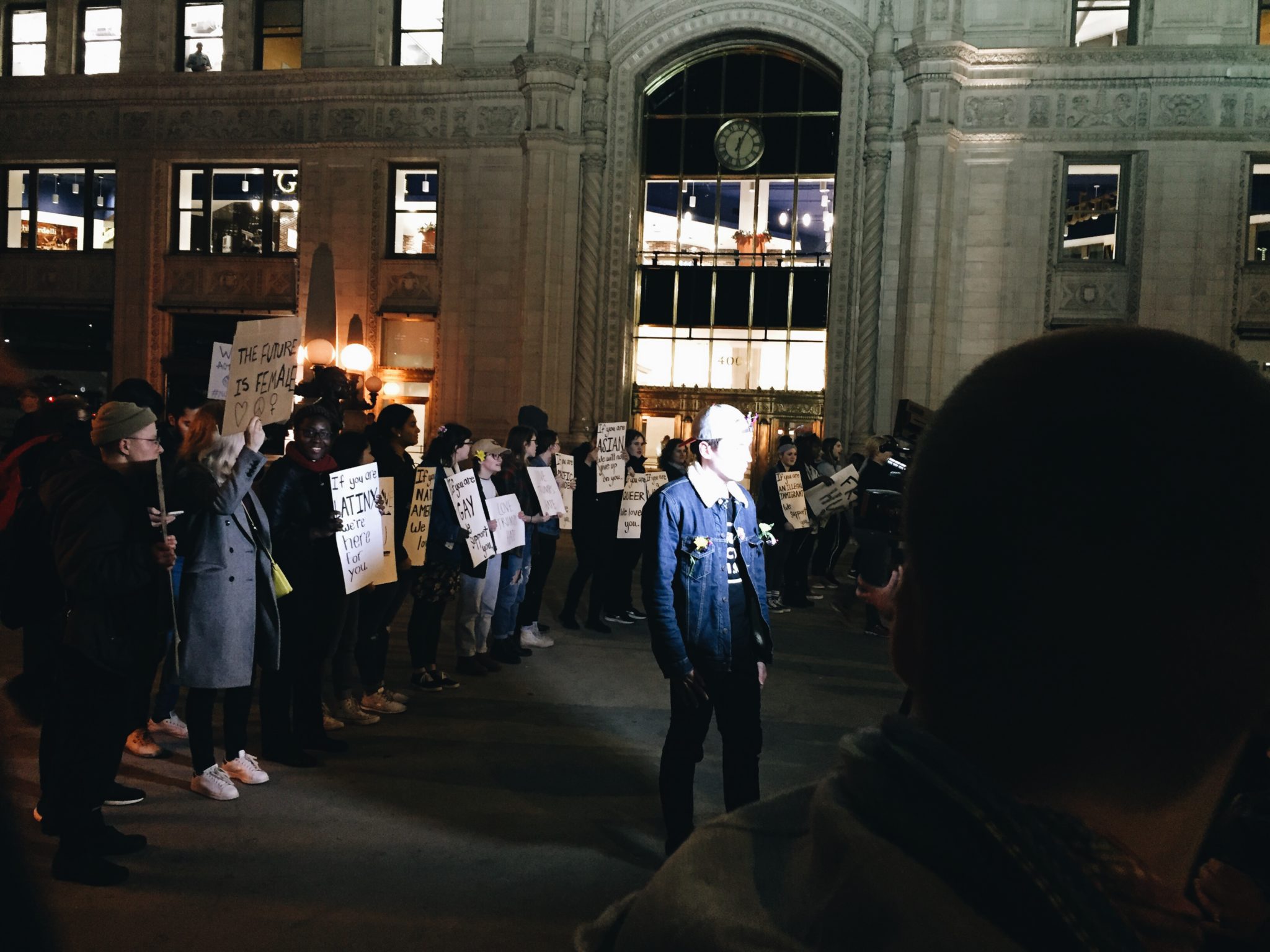

In the protests that overpower the streets of Chicago, I watch photographers utilize their craft to create powerful images that respond to the anger, the sadness, the frustration of all the protesters. I hear poets improvise slam through loudspeakers that help to harmonize the swirling thoughts of us all, using words like conductor’s wands to create a symphony of emotion. The photographers, the poets, the rappers, the skaters, the bikers, the painters, the writers, all of the creative minds that congregate to rally against Trump create a visual performance that demand response and empathy.

•

I remember going to a neighborhood association meeting in a church basement on 7 Mile. The leaves were in the throes of change and yet the neighbors seemed to be at an absolute standstill over a neighborhood curfew. Apparently some residents didn’t want the children from the surrounding neighborhoods to trick-or-treat on our streets.

A man at the podium suggested, “Let’s make sure to stop trick-or-treating in our neighborhood before nine to keep the outsiders out.”

God forbid the children from neighboring areas come to the “rich houses” just because they wanted king sized candy bars.

After that, and as a sign of rebellion, I would drive my white Prius over the small gardens, the green spaces, the beautification that made streets into dead ends.

I squashed nothing other than a couple begonias.

•

We are disquieted. We are discomforted. We feel the heft of the implications of the new regime of our country.

•

My boyfriend Ricky is a comedian studying at Second City. He told me about his cohort’s group chat going into a rage the day after the election. The group chat name was changed from Big Titty to #TakeBackTheStage as the comedy studies students discussed changing their final showcase to comment on the new president-elect, what it says about our nation, and their anger and discomfort. Ricky showed me the conversation and admitted that he worried about the success of their satire. It could easily turn into thinly-veiled and heavy-handed moralism, rather than utilizing the craft of comedy in a tactful and successful way. His comments about the way that we respond to issues by utilizing elements of our art’s craft bounced around in my head for a long time after.

•

Many things could easily be solved by humanizing one another, by listening and empathizing. As we crowd before the police line in front of the Trump Tower that night, all of our voices chorus together: “No hate, no fear, immigrants are welcome here.” But the collective grows silent as another chant begins, as the voices of the Latinx/Latin@ protestors ring out, protesting in Spanish.

The collective group chants “Black Lives Matter”. We raise our hands in solidarity and continue to shout, “Hands up, don’t shoot.”

The female protesters chant, “Our bodies, our choice,” as the male protesters echoed back, “Their bodies, their choice.”

•

I’ve been giving a lot of thought lately to the significance of the craft of our art, and lately my writing and surrounding writing community have only furthered my interest in the concept.

In Columbia’s writing department, ‘recalling’ is a practice writing students use to retell a particular moment in a story that was coming through strongly. I sat in class one day as we discussed Hubert Selby Jr.’s story Tra La La and listened to the students recall the story. They described the final gang rape scene, where the character Tra La La was dragged intoxicated into a car in an empty lot. Men lined up around the block to take their turn raping her. The men all complained that the car smelled like “cunt,” so Tra La La was thrown from the car and onto the lot pavement. There, she was penetrated again and again until she was covered in cum, blood, and piss.

We read Selby’s story to discuss craft and the style of his writing. Another student, after that recall, said that he had no sympathy for Tra La La’s character.

I myself was unable to separate style from content. While some writers regard craft as capital Platonic C Craft, I find the idea of isolating craft from content to be full of hubris. Craft is not some sacred thing, and writing is not a holy immaculate conception of an artist’s mind. Writing, and any other form of art, is a channel through which we discuss life. It’s not right to separate craft from real world issues. We are not all-powerful Gods of creation. We are simply humans, using art as a means to process the world around us.

In that class, I wrote a stylistic parody of Selby’s Tra La La. I imitated the style but mocked the content, two elements that my mind found inevitably intertwined. Using short, choppy sentences, and then long, meandering single-breath pages in the style of Selby, I chronicled my own experiences with sexual violence. I was told that my parody was disturbing. I was glad. I wanted my artistic response to be so emotionally intense, so saturated with personal experiences, that my audience would have no choice but to be discomforted in the face of my suffering—suffering they could not ignore as fiction or part of craft. I used my art to force an emotional response, to force empathy.

These protests above, and my own protest in my writing class, demonstrate the importance of encouraging, even forcing discussion through our art. Beyond forcing conversation, we also need to be listeners.

I remember months ago talking to Ricky about people he had known who grew up struggling with depression. I remember him saying, “Isn’t it like a self-fulfilling prophecy in a way—like horoscopes?” I remember the heavy silence that saturated the air afterwards.

“Well,” I remember telling him, “as someone with bipolar disorder, I can promise you that it is nothing like horoscopes.”

He apologized immediately and explained that he wanted to be educated. He wanted to learn more about bipolar disorder, and was warmly open to listening.

In the time since then, I’ve responded to the conceptual misunderstandings about my mental illness through exposure in my art. I’ve written prose, poems, drawn self-portraits—created things that explain my struggle, that force empathy and emotional response, and also help others to understand.

I’ve learned in my experience with my writing class and with Ricky, that I have the power to respond and communicate when faced with these issues. The photographers, the poets, the rappers, the skaters, the bikers, the painters, the writers that I marched alongside the night of November ninth hold an incredible power in their craft. We have the power to respond on our own terms to what the world seems to be unfairly demanding of us. We can utilize our art to create our own explanations, to represent our emotional responses, to portray our experiences.

We have this incredible power to engage people on our terms, on our turf, to create dialogues, to challenge people to question their own steadfast beliefs, or to correct misconceptions and misunderstandings. As artists we can communicate with our audience, we can engage our audience, and above all, we can be listeners. Listen to one another. Allow everyone’s voice to be heard. Share stories, share experiences, force discomfort, force empathy. Get off your mattress on your apartment floor. Create something.

Zoe Raines grew up in Detroit and moved to Chicago to study writing at Columbia College Chicago after transferring from The University of Michigan.