The boy’s hands crashed around the bird, easy as anything else. His body was rigid for a second, tense with disbelief. He wasn’t sure he’d even had anything in his hands until he felt the flutter, the soft and frantic brush of small feathers against the dirt caked skin of his palms. This was a first for the neighborhood, no one had caught a bird before. His hands, clumsy with inexperience, tightened ever so slightly against the bird’s small dusty brown body. He couldn’t wait to show his little brother and sister just what he had accomplished on this day. The oldest son, he set the standard, and now he had done the impossible.

The prize, won with more luck than skill, had really begun to writhe between his clasped hands, bringing into focus his next problem: how to transport the bird. No one would believe what he’d done if he had nothing to show for it. But the bird was not one to want to be conquered. The bird was pushing against the boy’s fingers, beak and claws scrambling, looking for the right pocket of light inside of the cavern of ten-year-old hands that it could worm its way out of. The boy tightened his grip, ignorant to gentle practice, and in one sharp movement he had exposed the bird’s head, emerging from his clutches into sunlight while its body remained in his hands.

But this emergence wasn’t the victory that either of them had hoped for. He had wanted to create a porthole window of tiny interlocked fingers, thumb over thumb and palms together, that the bird could stick its head out of. He had wanted to give the bird a little room to breathe, to look around, to be able to see all the other kids’ eyes go wide—wide enough to fully drink in what they were witnessing. Tiny faces filled with awe in the presence of glory. But orchestrating the movement of that which does not want to be moved is rarely accomplished without resistance. When the boy tried to push the bird towards an open space, the bird tried to dive away, the tension proving too much for its spine. There was a twist, and then a stillness. The boy felt something slip, pop, in the bird’s body. With the bird’s head finally breaking through sweaty fingers and into open air, the boy could now see all that he had done. That the bones in the bird’s neck must have snapped, that the tendons and ligaments must have torn, that the bird’s head was pinned to its back, white chest puffed out by this overextension. Its stark yellow beak opened wide and its head jerked forward with every gasping breath. But like it was tethered by an invisible piece of elastic, the bird’s head unfailingly slingshotted back to rest on its spine. The bird’s neck was broken, it was gasping for air. The bird was dying.

The boy’s body, every vessel and every cell, turned to lead in an instant— instinct knowing that this was wrong before coherent thought could catch up to it. Felt first in the stomach, then in the chest, a deep-rooted understanding that something had happened, and it can’t be undone. The numbness of a moment that can’t be taken back, a distinction now of a before and an after. The point of no return. He’d already brushed against this mistake a handful of times; all those grasshoppers whose legs would get caught up in the scuffle of capture were easy enough to brush off. A grasshopper would probably be dead in a few days anyway. The blue bellies he’d catch who’d detach their tails in defense, the brown blood that’d coat the inside of his hands each time, he’d never pay them much mind. After the blood dried and the tail fell to the dirt, the lizard would just run off as though nothing had happened. His dad had warned him now and then that he oughta be more careful with how he plays out here, that he oughta show more respect to life that withstands the desert. These were idle words once.

“What are you doing?” a little voice asked, setting the boy in motion again. His brother, the tow-headed baby, clad in only a dirt-dusted diaper and his taped together glasses, emerged from the side of their neighbor’s trailer. He had seen the boy struggling with something in the dirt, and knew that this had to be good—a big blue belly or, maybe if they were lucky, a garter snake. The boy flushed with panic. The success of his capture had soured in his stomach now that he realized that it had come with a price tag. Back turned to his brother, he looked down at the air-starved bird, trying and failing to get a full breath.

“I . . . I found this bird. I found this bird like this.” Without much thought he turned around, revealing the broken, heaving creature to the baby. The younger boy’s eyes went wide, not with the excitement or wonder that the boy had once envisioned, but with something entirely different—fear. The bird’s head lurched forward and snapped back again, eyes narrowed so much that they were almost closed.

“Why is it doing that?” the baby asked.

“I think something broke its neck,” the boy said. The lie almost caught in his throat, but he pushed through. If he could hold onto this lie, maintain the deflection of an ambiguous “something,” just keep it together, then maybe he could hide what happened—even from himself. He couldn’t be the one to have done this; to have destroyed this one good thing, and worse, confronted the baby with this reality. That it’s easy to destroy, that his own hands could do it. The boy retreated from the sagebrush and sand behind his parent’s trailer and started walking to the main road that sliced through the trailer park, the baby tottering quickly behind him.

The rectangles of multicolored trailers stretched down the blacktop road out front. The trailers faced each other on either side of the road, lined up on almost the exact same amount of property so that each front window could be seen from another’s front window. They were almost like rows of pews; the asphalt road between them the nave, and the foothills at the helm of the trailer park the altar. No pulpit, no preacher, just a congregation alone and unguided residing in tin- clad pews. The boy surfaced from behind a trailer that was about halfway down the road, one as blue as a robin’s egg. The other kids, who had been playing on the blacktop road out front, saw that the boy was cradling something and they quickly crowded around him, the bird, and the baby. Their excitement for what the boy had brought back for them to marvel at quickly dissipated when they saw the bird, its head at an angle a head should never be at, yet somehow still alive. Shame was crawling up from the boy’s belly as the kids started to shrink away from the bird. He wondered if they could see through to the horrible truth, that he hadn’t found the bird like this, that he had done this all himself.

“We should tell Dad,” his sister said, rubbing her sniffling nose with the back of her hand, “He’ll know what to do.” She wiped her snot on the side of her already-stained pink cotton shorts. The boy let his grip tighten around the bird at the thought of this, his legs stiffened and refused to move.

“We can help the bird! We have to!” The baby chimed in, pulling at the frayed hemline of the boy’s tan shorts. The boy’s sister and brother were younger than him by four and seven years, respectively—an understanding of “catastrophic” had not yet formed in their heads, hadn’t even dipped a toe. But the boy, he was old enough now to know what his father’s solution would be, only deepening the pit in his stomach.

“I’m going to get him.” The sister spun around and clamored up the steps on the side of the trailer and disappeared inside for a moment. When she returned, she trailed behind a hulking man. He had the same sandy brown hair as the boy, deep frown lines, and a baseball cap on the crown of his head that would’ve been black had it not spent so many sunny afternoons forgotten on the dashboard of his work truck. The amber beer in his hand sloshed around inside of the bottle as he made his way down the steps to assess the situation.

“The fuck you do now?” he asked the boy. His father took his free hand and put it on the boy’s shoulder, eyes settling on the dying bird in his hands. The boy felt his face get hot and he stared at the ground, praying to God that the swell didn’t breach the edge of his eyes. The hand on his shoulder squeezed him ever so gently, “Alright, come on now. Come with me.” His father shooed the other kids away, and guided the boy by the shoulder to the open mouth of the trailer park.

The trailer park was headed off by an old two-lane highway, one that didn’t get much action, and was more of a reminder of a time long ago. Town was to the east, California to the west, and south, directly ahead of them now, were the foothills—the altar, abandoned and unadorned. The mountain stretched up and up, spearing the sky, threatening to crack it wide open. When they reached the edge of the highway, the boy faltered. It was hot that day. The sun had beat down on that blacktop highway for hours now, heat springing up from the road’s surface bending the light around it to make it appear as if, in the distance, either end of the highway had been flooded with water. But there was no water here, there was no promise of salvation. There was only one direction the boy could go.

“Walk,” his father said. He proceeded without the boy. The boy swallowed around the lump in his throat and trudged forward slowly behind. The bird, still cupped in his hands, protested weakly. They trailed through the sagebrush, walking silently through the foothills, until they reached a tear in the earth. There was a pile of tires, some old, beat up and rusted-out cars, and discarded pieces of fiberglass and insulation littering this cut in the desert. “This is as good a spot as any,” The father said, stopping. He angled his feet sideways and started the careful walk down the sloped embankment. The boy beheld the ravine full of things that had outlived their purpose, the father figured it was just about as good as any graveyard.

In the desert gully, the father found an old wooden pallet and dragged it out into the open, laying it flat on its side.

“Alright now, set the bird down right here.” The father pointed to the pallet, sniffed, and spit.

“What are you gonna do?” The boy’s voice betrayed him, broke when he asked this question. He already knew the answer, but he needed to hear his father say it, he needed him to say it to make real what was already evident the second the boy had first cradled the bird between his fingers.

“It’s not what I’m gonna do,” his father sighed, “It’s what you’re gonna do. You gotta finish what you started.” The boy’s shoulders shot all the way up to his ears, his whole back knotted deeply into itself.

“No, no.” He whispered to the bird alone. He brought it close to his face, its beak almost fused open, trying desperately to get a bigger breath that was never going to come. The tears were streaming steadily now, he hoped his father would be kind enough not to notice this. “I-I didn’t do this,” the boy started to say, “I found the bird like this, I didn’t do anything, please Daddy, I’m sorry, please don’t make me—”

“Stop with the fuckin’ excuses,” his father cut him off. “I’m not making you do shit. You did this to yourself. I could tell by the look on your face when your sister brought me outside. The bird is suffering, the bird is dying. How many times did I tell you to stop fuckin’ around with the animals? You’re always sorry, never careful. You did this, now what are you gonna do about it? Are you gonna leave it to suffer, to die in your hands or, worse, alone on the ground just waiting for some cat or coyote to do what you ain’t man enough to do?” The father turned his back, walked a couple paces to the edge of the gully, as the boy, weeping, set the bird down on the wooden pallet. The bird flinched, outstretched its wings once more for the last time. It flapped and writhed, desperate to try and get out of danger, to fly away and find a way to heal or a quiet place to die. Its head, pointing awkwardly skyward till death, prevented any meaningful attempts at escape. This is where the bird would die.

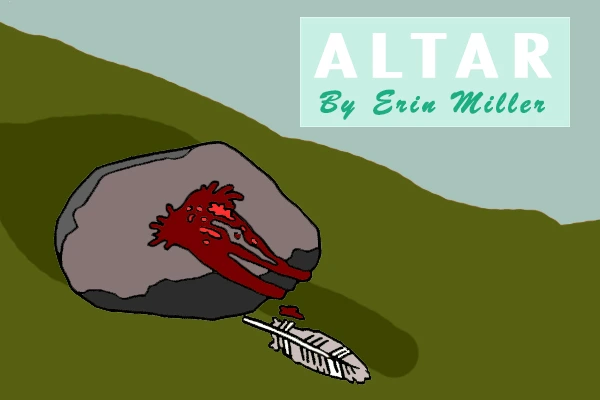

The father returned to the boy with a rock. Heavy, jagged, and warmed by the afternoon sun. Its surface was gray, and had sparkling flecks laced within it. The boy used to think these were pieces of gold, but really, they were all slivers of pyrite—fool’s gold. The father held the rock out to the boy, who reluctantly took it. His hands that had unintentionally maimed the bird now would purposefully finish the job.

“You’re gonna wanna be quick, but you need to have enough follow through to come down hard enough to kill it in one blow. Look square at it, you’ll always hit wherever it is you’re lookin’, so look at it dead on.” His father said, matter of fact. The boy knelt down beside where the bird was, trying to steady his breath. He looked at the bird, for the first time noticing the thin stripe of yellow that formed a ring around its neck. Except for the ragged breaths it kept trying to find, the bird was still. “Come on now, get to it.” His father’s voice softened a little, “Look, this is just what you have to do—it’s a kindness.” The boy closed his eyes, trying to still the heaving rise and fall of his chest.

“I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.” He whispered again to the bird, his voice stuck somewhere inside of himself. The rock was growing heavier in his hand, his wrist was beginning to ache. He had to do this now.

The boy raised the rock to the height of his shoulder and brought it down against the bird as hard and fast as he could. The rock connected with the bird with a wet crunch, blood splattered against the light grain of the unfinished wooden pallet, absorbing into the frame within a matter of seconds. He leaned the weight of his body into the rock—he wanted to do it right, not twice. The bird’s small bones succumbed to the exerted pressure, fractured, and splintered into nothing but red, sticky mush and copper-stained feathers.

The boy stood now on uncertain legs, watched as blood seeped out from beneath the rock pooling out into the dirt below the pallet. He turned to his father, and buried his face into the stomach of his black T-shirt. His father wrapped his arms around the boy, tight, like he meant it.

“I’m so sorry,” the boy wept, leaving teardrops down the front of his father’s shirt, “I’m so sorry.”

Erin Miller is a 25-year-old writer, born and raised in Reno, NV, most recently residing in Chicago, now living here and there. When not writing, you can find them playing guitar in a hardcore band, enjoying a cold one on the stoop with their best friends, or lighting off fireworks in the White Sox parking lot.