By Lorraine Boissoneault

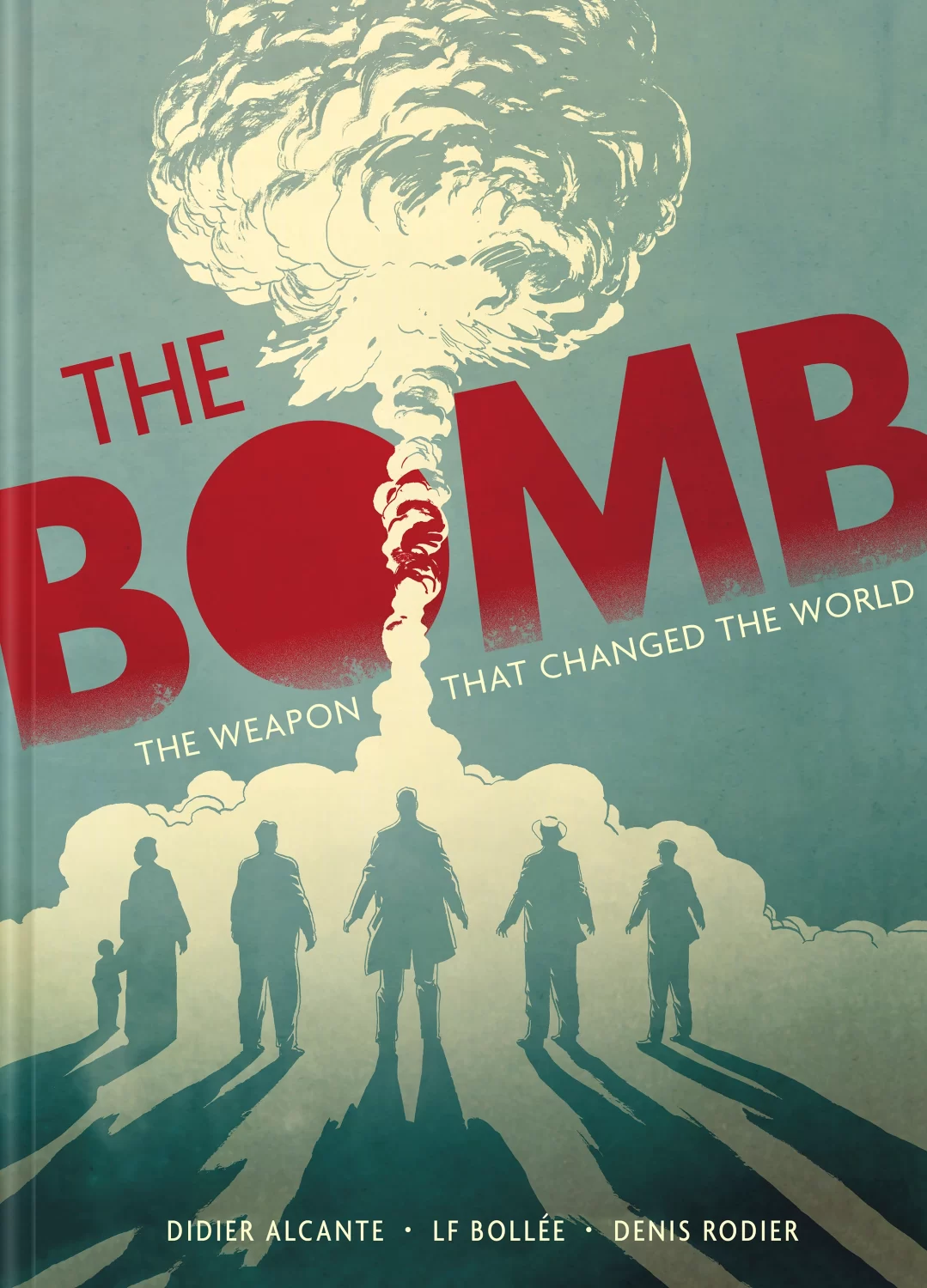

For anyone swept up in the summer movie bonanza dubbed “Barbenheimer,” it might be tempting to think that director Christopher Nolan is the artist best-suited to telling a story as sweeping as the development of the atomic bomb. But that’s only if you haven’t read The Bomb, by Belgian writers and illustrators Laurent-Frédéric Bollée, Alcante, and Denis Rodier. Their 450-page illustrated story is both deep and broad in its retelling of the people and events that surrounded humanity’s invention of nuclear weapons. Sometimes funny, often tragic, and always eye-opening, the book offers a thorough account of the motivations of scientists and governments alike. To learn more about the years-long creative process and collaboration required for the book, I spoke to all three writers and illustrators.

What did you think a graphic novel could offer that other books on the atomic bomb couldn’t?

Denis Rodier: I believe it’s the right medium as it communicates information quickly and effectively utilizing visuals while still allowing them to be thorough and historically precise. Told in prose, this type of story can get confusing with all its protagonists when the only thing the reader can hold on to is their names to identify them. Cinema tends to deal with history with oversimplification which adds to another set of problems when the story has to be told within a time frame of two to three hours. There, choices have to be made which is often detrimental to any sense of nuance.

Alcante: I am convinced that the graphic novel is truly the best medium to tell the story of the atomic bomb! The graphic novel uniquely combines text and images, harnessing the power of both the “graphic” and “novelistic” elements.

For such a story, the illustrations provide an undeniable advantage over historical books or novels. Apart from their intrinsic aesthetic and expressive qualities, they help bring the characters and their emotions to life. They also enable readers to visualize important visual elements more easily, such as daily life in Los Alamos, the gigantic factories in Oak Ridge or Hanford, the sabotage of the Norwegian plant, and so on. And of course, Denis’ illustrations have an extraordinary power when depicting the atomic explosion and its effects on the city of Hiroshima and the victims! In fact, we chose to leave those pages with minimal text, as the illustrations spoke for themselves at that moment.

Laurent-Frédéric Bollée: In our book, we show two explosions of two atomic bombs: the one from the Trinity test and the other which, as everyone knows, wiped Hiroshima off the map. In cinema, this would require considerable resources. The strength of comics, then, is that they can more easily accommodate such representations. And since our aim was really to get a “panoramic” view of this build-up to the A-bomb, on several fronts and continents, our medium was able to combine words and images in a striking way.

Why did you decide to use uranium as one of the characters for the book? More than any of the humans, he seems to unambiguously revel in the power of such a horrific explosion.

Alcante: We wanted to have a narrator to avoid overly descriptive narratives that could have been boring. Ideally, the narrator should literally traverse the entire story, but none of the characters fit that role. None…except uranium! It is inevitably present during the realization of the first chain reaction in history, as well as in the laboratories of Los Alamos and, of course, in Hiroshima during the explosion. Therefore, we decided to make uranium the narrator. From there, we needed to find its tone, its voice. We chose to give it an unsettling aspect, making it speak like a sort of indifferent god to the fate of humans, sensing that it has a “destiny” to fulfill.

Bollée: The easy thing to do would have been to have the bomb itself speak, biding its time during all those years of war, just waiting to explode… But we opted for a slightly more subtle and unexpected approach, namely uranium, a mineral and the real “fuel” of the bomb, the essential and almost “diabolical” substance of this story. So, certain of its power and importance, we personified it to make it an almost “superior” voice, sure of its role and impact on the world. In the end, uranium had only one role to play, and it was to play it like a demiurge.

Rodier: I would add that no one character in the story would be able to be a believable narrator of the events as no one was ever a witness to everything that happened.

I imagine there have been tens of thousands of pages written about the Manhattan Project and the aftermath of the bomb. How did you choose which scenes to illustrate and what information to leave out?

Alcante: There is indeed a lot to tell about the history of the atomic bomb, and we had to make choices. In the afterword, I explain that I could still write 2,000 pages on the subject, and it’s truly the case!

We couldn’t tell the story of the atomic bomb without mentioning the U.S. entry into the war, and therefore Pearl Harbor; we had to address the major milestones in the development of the bomb, such as the first controlled chain reaction in history (in Chicago), the Trinity test, and of course, the bombing of Hiroshima.

Then, the choice naturally occurred once we had our main characters: primarily Leo Szilard, but also General Groves, Oppenheimer, Fermi, and Naoki Morimoto, the resident of Hiroshima.

My main regret is not being able to include Niels Bohr, a colorful Danish physicist who served as a mentor to most atomic physicists of the time. He also worked himself on the Manhattan Project. But there simply wasn’t enough room to speak about him.

Bollée: We knew that our book would be around 450 pages long, which is already quite a lot, and would involve five years’ work! So, after a lot of reading and viewing for documentation purposes, when we had all our material in front of us – well, we had to make choices! Certain stories in history seemed unavoidable, not to mention the desire to have an international vision (Europe, and Norway in particular, but also, of course, a strong desire to recreate life in Hiroshima before August 6, 1945). In short, an editorial choice was made, based on what seemed important or little-known, strong or interesting to us.

Rodier: We needed to avoid a Manichean worldview with good guys versus bad guys. Some choices were also hard to make as it is tempting to insert some interesting anecdotes just for the sake of it.

I had no idea that there was a concerted effort to build an atomic bomb in Germany during the war, and really enjoyed learning about all the Allied efforts to thwart it. But it also seems like the Germans never got very far. Do you think they had even a chance of success?

Alcante: Germany did indeed have many advantages when the famous race for the atomic bomb began: great scientists, industrial power, access to uranium, and military and political figures who were informed earlier than their counterparts in the United States. The German War Ministry was informed as early as April 1939 about the possibility of using nuclear energy to develop a bomb much more powerful than anything that existed at the time! They had a six-month head start on the Americans at that time.

And yet, ultimately, the Germans were (very) far from achieving an effective atomic bomb.

Several reasons explain this.

Firstly, there was a brain drain. Many Jewish scientists and researchers who could have contributed to the development of the atomic bomb fled Nazi Germany (or fascist Italy) due to political persecution and the growing threat of war. Some of them emigrated to the United States, where they played a key role in the Manhattan Project.

Secondly, during the war, Germany faced limited resources due to economic constraints and the need to allocate them to other military priorities. The atomic bomb project required significant resources in terms of materials, manpower, and infrastructure, and Germany was not able to mobilize them adequately.

Moreover, the Nazi regime made strategic choices that diverted resources from atomic research. For example, priority was given to the development of V2 ballistic missiles rather than the atomic bomb. In this regard, there are still questions about the role played by Werner Heisenberg. This Nobel Prize-winning physicist (1932) headed the German atomic bomb project, and in June 1942, he discouraged the German Minister of Armaments from pursuing that path. It is still unknown whether he did so due to moral thoughts to prevent Nazi Germany from developing the bomb or if he genuinely did not believe in its feasibility himself.

Furthermore, the Allies became aware of Germany’s efforts in the nuclear field and carried out sabotage operations to disrupt the program. As depicted in our graphic novel, the Allies notably destroyed a significant heavy water production site in Norway, which was essential for German nuclear research experiments.

Finally, it should be noted that Germany was heavily bombed day and night towards the end of the war, making it simply impossible to develop the enormous infrastructure necessary for the production of enriched uranium or plutonium.

It is worth mentioning that besides the United States and Germany, Japan, England, and the Soviet Union also had their own atomic weapon development programs during World War II. We also address these aspects in our graphic novel.

Bollée: No, they couldn’t have succeeded. But we didn’t really know that until after the war. And between 1939-42, we could really only quake at the way the Third Reich was advancing its projects.

Dr. Szilard was a particularly interesting character because he goes from championing this research to very actively denouncing its use. What do you make of his about-face?

Alcante: Leo Szilard, the main character of our graphic novel, is a scientist of Hungarian origin who fled Germany in 1933 and eventually ended up in the United States. He played a major role in the history of the atomic bomb. He is someone I admire and find fascinating. Unfortunately, he is not well-known to the general public, and I hope that our book will help bring him to the forefront.

For me, he is simply one of the greatest scientists of all time, but also fundamentally a great humanist and a man of action.

I understand that you mentioned an “about-face” regarding Szilard because he initially did everything in his power for the U.S. to develop an atomic bomb (he wrote the famous letter to Roosevelt, signed by Einstein, which initiated the Manhattan Project), and later on he actively campaigned against the actual use of the bomb on Japan (and rallied scientists from the Manhattan Project to sign petitions against it).

Nevertheless, I believe that the term “about-face” is not appropriate. In my opinion, Szilard never changed his guiding principles, which were resolutely pacifist and realistic at the same time.

Initially, in July 1939, Szilard was convinced (rightly so) that Nazi Germany would attempt to develop the atomic bomb, and that the only solution to prevent Germany from using it was for the U.S. to develop their own bomb. The idea was, therefore, one of deterrence, a credible threat of nuclear retaliation to make an attack too risky to undertake.

Thus, it was essential to create this bomb – one can only shudder at the thought of a world where Hitler possessed nuclear weapons before anyone else – but it was conceived in Szilard’s mind as a deterrent against Germany. It was in this context that he drafted the letter to Roosevelt, signed by Einstein.

However, when Germany surrendered (along with Mussolini’s Italy), and Japan became the last enemy to defeat, the situation was completely different. Japan did not possess nuclear weapons; that was certain, and they were on the verge of surrender. They were no longer capable of launching an attack, with almost no naval or air force remaining, and no allies.

Consequently, at that point, the American atomic bomb had nothing to do with the initial context. It transitioned from being a deterrent against Germany to an offensive weapon against Japan!

It was against this use that Szilard vehemently fought, proposing instead a peaceful demonstration of the bomb on a deserted island in front of a panel of representatives from around the world, including Japan, to give Japan the opportunity to surrender with full knowledge.

He feared that the actual use of the bomb would result in a massive loss of human lives, especially civilian lives, and that it would also trigger a dangerous nuclear arms race, making the world less safe. Instead, he advocated for international control of nuclear weapons.

As we all know, that was not the path taken, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed. The nuclear arms race began, reaching its peak with 70,000 nuclear weapons worldwide during the Cold War!

In my analysis, it was not Szilard’s guiding principles that changed, but rather the evolving historical circumstances that forced him to adjust his stance while maintaining the same objectives.

Bollée: He can truly be considered one of the fathers of the atomic bomb, but his activism proves that some scientists realized before others where we were heading…and in this, his behavior is admirable. Even if his petition of July 1945 got lost in the labyrinths of the American administration, it has the merit of having existed, and of being proof that this scientific (or military) breakthrough could not remain without questioning and interrogation. Which must still be the case today, of course.

Rodier: Scientists will always be champions of scientific discovery and as with everything in science, you can’t “undiscover” things. Szilard’s story arc in the book shows a humanist trying to stop evil with science and then trying to put the genie back in the bottle to prevent misuse of those discoveries.

The pages dedicated to the explosions in Japan are really powerful. What was the message you wanted to convey about the civilian victims of these bombs?

Rodier: Those scenes were very difficult to draw as we didn’t want to make it into a cheap horror movie. Respect towards the victims was imperative while, on the other hand, we felt the need to fully confront the effect of the bomb on the civilian population.

Alcante: I visited the Hiroshima Museum when I was eleven years old, and it left a lasting impact on me. I was particularly struck by the drawings made by the survivors of the explosion. The scene was truly horrific. The victims were nearly naked as their clothes had burned off. With the extreme temperatures from the blast, their flesh had literally melted away. Many survivors threw themselves into the river to alleviate their suffering from the burns. It was truly apocalyptic imagery.

I didn’t necessarily want to convey a specific message, but rather to show the horrifying reality. I believe that anyone would be shocked by it. We’re talking about the near-instantaneous death of tens of thousands of people. I think the best way to truly make people understand was to show it explicitly, without voyeurism or exaggeration, but as it was.

To me, it seems that any reflection on the use of the atomic bomb must include this perspective of what it truly represents.

Bollée: Here again, we let history speak: it was on a Japanese city that the first “intentional” atomic bomb fell, wiping it off the map, killing 70,000 people instantly and more than 200,000 in the decades that followed. We feel obliged, beyond the political and military oppositions of the 2nd World War, to be moved by this tragedy of humanity, and to stand by the dead of Hiroshima. Hence our desire to recreate the fate of a fictitious man [in the story], father of two, who symbolizes all the victims, so that they are not forgotten.

Having an atomic bomb as a form of deterrence is a major political argument in favor of its creation. But do you think at this point we should be more active in trying to get rid of all of them?

Bollée: According to the latest rough consensus figures, in 2021 there were over 13,000 nuclear weapons on Earth, most of them with a destructive capacity greater than the explosive that leveled Hiroshima. A war involving less than 1% of today’s nuclear arsenals would jeopardize the planet’s food supply, as demonstrated by an article in Nature magazine in 2020. It would seem that everything that has happened since 1945—the Cold War, the nuclear war between the USA and the USSR—has been a successful deterrent and has contributed to world peace. But at what price? The price of living permanently under the threat of a mad dictator, or of a blunder, a computer bug or a misinterpretation? In that case, such a quantity of weapons is chilling, and personally, I’m in favor of non-proliferation or even a ban on such weapons.

Alcante: Having visited Hiroshima three times, I naturally dream of a world without nuclear weapons. However, we must base our actions on the world as it exists, not as we wish it to be. In this context, the question of nuclear disarmament is an immensely complex debate. Just think of what could have happened if Russia, under Putin, were the only country to possess nuclear weapons—having our own nuclear capabilities would be seen as preferable. Once again, it comes down to the question of nuclear deterrence, which lies at the heart of the issue.

Nevertheless, there are inherent risks associated with the possession of nuclear weapons, such as proliferation, nuclear terrorism, human errors, and accidents. Nuclear weapons pose a threat to humanity and the environment due to their potential for massive destruction. Pursuing their total elimination reduces these risks.

Again, Szilard was indeed a pioneer in this regard. He advocated for international control of nuclear weapons and cooperation in this area. This is partly what has been happening since the end of the Cold War, particularly with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1970). It is important to continue along this path. Efforts to strengthen the NPT and other arms control agreements, promote transparency, and build trust among nations are crucial in moving towards a world with reduced nuclear risks.

What do you hope readers take away from this story?

Alcante: I know that in the USA, the prevailing opinion is that the use of the bomb was justified and seen as a necessary evil, in the sense that it brought an end to the war and prevented a land invasion of Japan, thus “saving” a great number of American soldiers’ lives.

This argument is not without merit, but it really needs to be put into perspective, and the situation appears much more complex to me. I hope that our book will allow readers to have a clearer, more comprehensive, and objective understanding of the various events that led to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And I hope that after reading it, they will truly feel that every effort must be made to prevent such tragedies from happening again.

Bollée: First, the pleasure of learning things, to know that hidden behind certain historic facts there are stunning and sometimes incredible human stories. Next, there is the incontestable requirement of memory: to know in order to better understand, to not forget, maybe to forgive. As our book shows, there’s always a context to every story or event: here, because of the war, and out of fear of a terrible threat (that Hitler would get the atomic bomb), renowned scientists and superior intelligences got together to produce the most horrific weapon of mass destruction in human history, without too many qualms (hence the importance of the exceptions I mentioned earlier). More than 70 years on, it’s a compelling story.

Rodier: That history is made of a lot of moving parts and oversimplification of events can be detrimental to how we understand them. Our duty to remember is also a duty to understand what led to those events.

Interview Note: Laurent-Frédéric Bollée’s responses have been translated from the original French.

Alcante has been fascinated by comic strips since he was young. Originally a graduate in economics, he began his writing career in 2002. He has now authored more than sixty graphic novels and is currently working on an adaptation of Ken Follett’s international bestseller The Pillars of the Earth. Deeply moved by his visit to the Hiroshima memorial when he was eleven years old, Alcante has since spent an enormous amount of time researching the subject. Much of that research informed his approach to writing THE BOMB. He lives in Brussels, Belgium.

Laurent-Frédéric Bollée has been a successful journalist and writer for more than 20 years. Alongside his media work for various television and radio networks, he has also published nearly 40 graphic novels, including a volume in the XIII Mystery collection (part of the internationally acclaimed XIII saga). Bollée lives and works in Versailles, France.

Denis Rodier began his illustration career in 1986, which led him, two years later, to the world of comics. Among his first work was a Batman story in Detective Comics (1988), and his portfolio includes other world-famous characters such as Wonder Woman and Captain America. In addition to his work for DC Comics and Marvel Comics, Rodier has also worked for Milestone Media, Dark Horse, Malibu Comics, and Image Comics. However, it is his work on Superman that has garnered Rodier his greatest acclaim. From 1991 and 1997, he was an inker on Action Comics and The Adventures of Superman, most notably on the award-winning, seminal “Death of Superman” storyline. Rodier lives and works in Canada.

Lorraine Boissoneault is a Chicago-based writer who covers science, history, and human rights in her journalism, and explores more fantastical worlds in her fiction. Previously the staff history writer for Smithsonian Magazine, she now writes for a wide number of publications. Her essays and reporting have been published by The New Yorker, The Atlantic, National Geographic, PassBlue, Great Lakes Now, and many others. Her fiction has appeared in The Massachusetts Review and Catapult Magazine. Her first book, The Last Voyageurs, was a finalist for the Chicago Book of the Year Award. She has received grants and fellowships from the Society for Environmental Journalists, the National Tropical Botanical Garden, and the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources. She has also appeared on documentaries and radio stations like the BBC to discuss American history.