By Rachel Swearingen

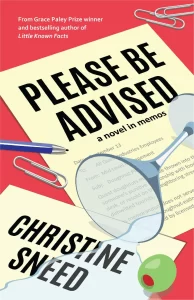

Several years ago when I was still new to Chicago, Christine Sneed invited me for coffee at Kopi Cafe, an eclectic restaurant in Andersonville on the northside of Chicago. Sneed, lithe and ageless, showed up on her bicycle, pulled off her bike helmet and apologized for being sweaty. I didn’t know her well. She was disarmingly friendly, in the way many Midwesterners are, especially Chicago authors who tend to pride themselves on being unpretentious and welcoming. Inside the café we sat at a table under a wall of clocks—set for Chicago, and for other far-off locales. (Sneed, a longtime resident of Chicago, would soon relocate to the West Coast.) Within minutes we were trading stories, laughing about our Midwestern proclivities, discussing our work. A versatile writer, she had several projects going at once. She would draft new stories in the kitchen of her small apartment while her partner cooked. One of the projects she had underway was her forthcoming novel, Please Be Advised, a ribald romp through inappropriate office culture cloaked in Midwestern politeness.

Told through a collection of increasingly farcical memos, Please Be Advised follows the inner-workings of Quest Industries, a manufacturer of collapsible office products. Each memo is written by a different faction or employee—from the oversharing, retiring office manager Dottie Wright to the overprivileged bore of a president, Bryan Stokerly, Esq.

The memo, well on its way to becoming an artifact of simpler technological times, is a perfect vehicle for satirizing American culture. The troubles that arise from the exchange of these memos are not that different from that of a tweetstorm today. There are confessions and scandals, unveilings of absurd policies, stories of divorce, dating, and loneliness, rumors of embezzlement and tax audits, as well as heartfelt motivational messages. Technology may change at a rapid pace, Sneed seems to imply, but human desires for influence, power, and wealth—as well as for recognition and connection—remain unchanged.

Please Be Advised belongs to the long tradition of work-culture satire, and there are echoes of Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” as well as Julie Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members and Greg Daniels’s television series The Office. Christine Sneed is a generous storyteller. The pages fly as you laugh out loud and realize too late that you have already placed yourself within the hierarchy and declared your own loyalties. This deceptively delightful novel will leave you in uncomfortable stitches.

Please Be Advised is such a funny and entertaining book. What inspired you to write it?

Thank you—I’m so glad you think so. Humor is inherently subjective, whereas what’s considered serious or dramatic is more likely to create a consensus among readers (you can’t really argue with the sadness of someone’s child or mother dying in a plane crash, whereas whether or not you think a person carrying a full bag of groceries slipping on a banana peel is funny is anyone’s guess.) I was working on a different comedic novel before I started Please Be Advised, and when I finished that other book, I didn’t want to stop writing in a comic vein, but I was very tired from working so intensively on that more traditionally structured novel.

So, I started writing memos, thinking there would likely only be a few of them, but I kept going and eventually realized I might have the basis of another novel. I wrote much of this book in late 2017/early 2018, and would look at it from time to time and did send it out to a couple of book contests, but it lived almost exclusively on my hard drive until I sent it to Kurt Baumeister, a novelist himself (Pax Americana) and an editor at 7.13 Books. He was enthusiastic and eventually he talked with me about adding new plot threads along with punching up some of the jokes, and I still can’t quite believe it’s now a book. It’s very close to my heart—humor is by far my favorite mode, and has been ever since I started writing with serious purpose in college.

What’s the secret to writing successful humor?

I’m not sure if there’s a secret, but I think successful humor is almost always highly specific. The pleasure for me in a good book or film is almost always in its specificity. Great comedians are so observant, and I found as I was writing Please Be Advised that the memos I liked the most all had real-seeming, precise (albeit sometimes-odd) details.

Tangentially, one of the best comedic films I’ve seen in the last ten years is Lake Bell’s In a World…she wrote the script and starred in it and it’s criminal it’s not better known. Bell and her cast are uniformly terrific. How she used unique details to draw each character and the hilarious absurdity of some of the scenes—it’s so brilliant and at times unbelievably delightful.

The peculiar details in Please Be Advised are one of the novel’s splendors. You mentioned working on a more traditionally structured novel before this one. Did you approach Please Be Advised differently than your previous books?

I don’t know if I approached the writing of this novel differently than I did with previous books. I initially intended only to write a couple of thematically linked memos and send them out as flash fiction (ZYZZYVA and Catamaran Literary Reader did publish some of them, which helped me believe there was an audience for this type of book), but I enjoyed this form so much and kept going. I saw an opportunity here to write from many points of view too and explore the absurdity that often permeates corporate America, which fortunately happened pretty quickly. (I’ve worked in corporate, non-profit, and university offices, and although there were differences, there were also quite a few similarities among them.)

The writing of Little Known Facts, my first novel, began similarly. I wrote the first chapter as a stand-alone short story in the fall of 2010 but found myself still thinking about those characters. The spring of 2011, I wrote another story about them, and two or three more in the span of a couple of months, and I thought (as I later did with Please Be Advised), “Maybe I have a novel here.”

Each memo is somewhat like a short story, but the overall book has an expansive feel. Why the memo? What drew you to the form?

I used to teach business writing courses at Loyola University and DePaul University, and I really enjoyed it because for one, the techniques for writing effective business correspondence are more or less straightforward from a pedagogical perspective, whereas creative writing pedagogy is more subjective and relies heavily on the preferences, prejudices, and personal practices of each individual instructor.

I do think you can teach most students how to write an easy-to-read, specific, well organized CV or cover letter, but it’s not so easy to teach them how to write a short story, poem, or essay with real literary merit—the quality of which is much more subjective too—especially in a ten- or fifteen-week course.

The memo is like a poem though: it is generally stand-alone; it makes use of compression; and often it is short—an elegant little word parcel. And the possibility for humor in business writing is always there—intended or not. Even the alternate name of a “bad news” memo, a “sensitive” memo, strikes me as funny. And the contortions corporations go to not to say specifically what is being done poorly or when something is going off the rails, well, that is essentially exactly what I set out to do in Please Be Advised, i.e. say all the things you’re not supposed to say in office correspondence.

How important was it to you to work a sense of character and plot into this non-traditional book?

It was crucial. I really tried to build a quasi-realistic corporate environment in Please Be Advised by writing in the voices of a few dozen recurring characters. I also intended to use plot to propel the book forward by including threads that ran the length of the book in some cases—I wanted this novel to have different dramas playing out over the course of its more than 250 pages.

As mentioned, Kurt, my editor, suggested including a couple of new plot points after he accepted the book for publication, and he also nudged me in the right direction when I mentioned what I was thinking of adding—the IRS audit thread came about through an early discussion with him. I also added to the office matchmaker thread in subsequent drafts, and there’s a thread about Ken Crickshaw’s missing son.

As far as characters go, I’m partial to Ken Crickshaw. Who was your favorite character to write and why?

Ken is my favorite character too! I see him as the novel’s moral compass. Even though he certainly has flaws, Ken is always trying to improve the quality of life of his Quest Industries colleagues, but sometimes pays the price for it, in part because President Bryan Stokerly, Esq. paints Ken as a bad guy in more than one memo after Ken launches new initiatives to make Quest a more healthy workplace (treadmill desks, free medical advice on Thursday afternoons, removal of the office’s numerous candy dispensers, to name a few of his projects).

As I wrote his memos, I also imagined Ken as someone frustrated by other people’s laziness and ignorance—he works very hard and is well meaning and intelligent and doesn’t suffer fools, a curmudgeonly ethos that slips out in more than a few of his memos. Stokerly, at heart, is jealous of Ken, and both men know it. Nonetheless, I saw them both as opportunities to heighten the tragicomedy of all the absurdities that abound in a corporate setting, especially the doublespeak that often rules the day. In college, I took a course titled “Management Organizational Behavior,” and learned how the Saturn car company, I think it was, used the word “opportunity” instead of “problem.” At the time I was impressed, but now I think, “Who the hell were they kidding?”

Above all, I value candor, not subterfuge. There are ways to be tactful and honest (which was a skill I tried to teach students when they were writing a “bad news” memo).

What is it about American corporate culture that interests you, or that you would most like to see change?

As alluded to above, the spark for this novel was my mildly iconoclastic desire to write about a corporation staffed by people who blurt out whatever is on their minds, essentially, characters who say all the things you’re not supposed to say at work if you don’t want to be fired and/or you want other people to like you. I do value tact, and it’s not that I want people to be rude or insensitive, but I also wish we could speak our minds more often and not be punished for it. This seems especially important in an age when people are silenced on social media or in other forums for voicing an opinion that isn’t popular or challenges the status quo. There’s a lot of virtue-signaling, and I wonder how much of it is sincere. And on a related note, why have we allowed our society to be fully overtaken by the profit motive?

One cri de coeur here: the valuing of profit over all else has helped to create the extreme wealth disparity that is one of the main causes of the enormous political polarization in the U.S. (and elsewhere). It’s such a sleight of hand that conservative politicians have been able to convince the working class their respectably paying jobs have disappeared because of maneuvers by the left when the truth is the blame belongs more to CEOs and their boards of directors, with help from the Supreme Court and other legislators. Even though this novel is above all comic, these situations underpin it, and CEO Bryan Stokerly, Esq. is their avatar.

You moved from Chicago to L.A. several years ago. What’s your writing space and process like these days?

I write in our apartment’s second bedroom; I don’t have an established routine, although when I’m working on a new novel, I try to set word-count goals for each day. My long-time domestic partner Adam is very tolerant of the balancing act I have to maintain in order to teach, do administrative work for one of the schools I teach for, and keep writing. He reminds me to rest and get outside when I’ve been at my desk too long answering emails, critiquing student work, and trying to get a few hundred words of fiction on the page.

It would doubtless be helpful if I had a more stringent, consistent writing schedule, at least during the weekdays, but so far I haven’t been very good about coming up with one I’ll stick to. Early morning is the most productive/energetic time of the day for me, but it’s also when I like to do errands and exercise. The errands and exercise often win out, because there are fewer other people doing their shopping at that time, and the day isn’t yet blazing hot here in Pasadena.

I hear you’ve been writing screenplays and TV series. What are you working on now?

I’m working on a feature script based on an unpublished novel of mine, and I’m also slowly writing a couple of novels that I started in 2020, neither of them comedic, though I think there are flashes of humor in both. I peck away at a number of my scripts from time to time too—sometimes preparing them for one of the myriad contests out there (which you can blow a whole lot of money on, but I focus on a handful that are topnotch: the Nicholl, Austin Film Festival, Screencraft, and CineStory).

The short fiction anthology you edited, Love in the Time of Time’s Up, launched this month as well, and your third collection of short stories, Direct Sunlight, will be available in June. Can you leave us with one piece of advice for writers struggling to get their work out into the world?

I’m so glad to have a terrific story by you in the anthology—which I’m really looking forward to seeing in the world on October 4, one day before the five-year anniversary of Megan Twohey (who is from Chicago) and Jodi Kantor’s story in the New York Times about Harvey Weinstein’s decades-long stint as an unchecked serial sexual predator.

As for a piece of advice…well, I suppose I’ve said this at other times but I think it bears repeating. You have to feel that the writing itself is its own reward because fame, fortune, big awards, best-selling books—those things are never guaranteed and very hard to achieve, even if you’re putting all of your time into promoting your books (which I don’t recommend – aside from alienating friends and family, the writing itself should always take precedence over its promotion).

As the poet Roland Flint (and former professor of mine, dead now 21 years) once said, “The work is all,” i.e. you have to love the process of writing, because if you don’t, you should do something else with your life.

Christine Sneed’s writing has appeared in publications including The Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Prize Stories, New York Times, and Ploughshares. She teaches creative writing for Northwestern University and Regis University, and has received the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction, the Chicago Writers’ Association Book of the Year Award, the Chicago Public Library Foundation’s 21st Century Award, and has been a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She lives in Pasadena, CA.

Rachel Swearingen is the author of How to Walk on Water and Other Stories. Her stories and essays have appeared in Electric Lit, VICE, The Missouri Review, American Short Fiction, Kenyon Review, Off Assignment, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago.