By Eileen Favorite

I met Suzanne Scanlon during a Ragdale residency many years ago. It was springtime, the prairie muddy, the trees just starting to bud. Our stay landed during Holy Week, and we discovered that as children, we’d both been ordered to be silent from noon to three every Good Friday, to honor the crucifixion of Christ. I’d never met anyone else in my adult life who’d followed this Irish Catholic tradition, and we bonded over the morose exercise of no TV, no radio, just thinking about Christ’s death for a few hours. We agreed that it was always cloudy during those three hours.

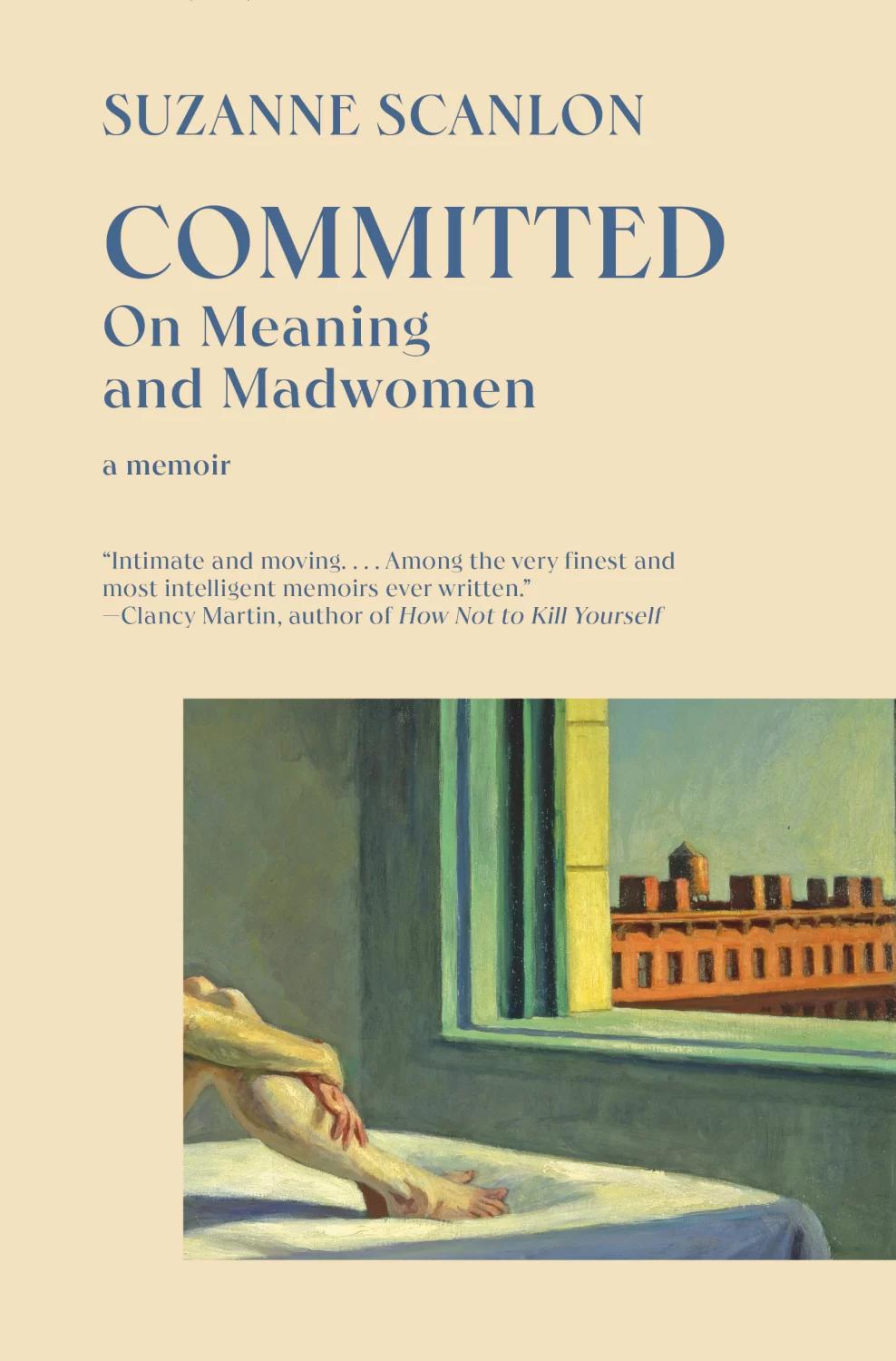

In her new memoir, Committed: On Meaning and Madness (Vintage), Suzanne interrogates her artistic development through the lens of women artists who, like herself, struggled with grief, hospitalization, and learned how to exist in a world that doesn’t value the sensitive spirit, the creative soul, and that sometimes actively seeks to crush it. Marguerite Duras, Audre Lorde, Janet Frame, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Kathy Acker, Shulamith Firestone and many others held a torch up in the darkness for her. Lucky for us readers, Scanlon has shared her powerful journey and graceful prose in this extraordinary memoir.

Eileen Favorite: When you say on page 17, “I got better at being sick. I got better at being a mental patient,” I thought about how we’re drilled as girls, and especially as Catholic girls, to be “good.” You analyze the woman in “The Yellow Wallpaper” as “living up to the diagnosis she asked for.” The asylum becomes another place to be good or to please the authority figures. But you also talk about how they said you had to get worse before you could get better. How would you say that the system defined “worse”? What did it look like?

Suzanne Scanlon: Worse meant becoming more dependent. It meant going through a kind of therapy that unearthed all sorts of pain, memory, trauma, and really exploring it. In that way, it was informed by psychoanalysis (and some would argue valuable). You have therapy with a doctor three days a week, and then other therapy groups, activities, and all of it was meant to lead you on journeys into uncovering your trauma, the details around it, and how it informed who you are now. That is, your symptoms. Another part of this was getting worse through symptoms. And the symptoms were what people came in with but also what we learned from each other while inside. Cutting, eating disorders, acting out, rages, even smoking, however minor, was an option there, another bad habit to take up. Other things like saving up pills, refusing medications, suicidal ideation or attempts. Again, I’m not saying these didn’t come out of real suffering or pain, or that we didn’t need help, but as Erving Goffman points out, there is something about the context of the institution that encourages the patient to heighten these symptoms, in order to please the caretakers and thus receive more care.

For me, worse really meant that soon enough I couldn’t imagine not living on my own–and by then, I wouldn’t have been allowed to. I was basically committed by then. Worse also meant that all of these issues below the surface (grief, rage) were brought forward and became things I considered and thought about and focused on in a really intense daily way, to the exclusion of much else. To a paralyzing extent. That’s worse. The focus wasn’t really on coping skills, which I had to learn later.

Yes, you talk about how, when you returned to Barnard, commuting from the hospital, one of the deans told you, “They’re holding you back in there.” Did this sort of assessment provide a path toward a different sort of coping?

Yes, I didn’t realize at the time how important this was. Now as a teacher, a mom, probably the same age as the Dean was then, I realize that she was a voice of reason–a reality check. This is something I would say to my younger self now, if I could. It was a reminder that I could do it: have a normal life. A vote of confidence. A warning.

The dean’s words happened at a moment when you were ready to hear something simple and true. You were somehow open and her words registered. You talk a lot about this sort of receptivity in terms of literature, as well. When you read Duras for the first time, it was a kind of breakthrough: you were a particular age, in need of a particular voice, and there she was. Can you expand a bit about your concept of DurasSpace?

I needed to understand how far someone could go with extreme emotional experience, and what was valid for women. It was thrilling to discover a writer grappling with this psychic difficulty and negativity. I needed a model of sexual awakening and the way it could be totally transforming and annihilating. The Lover is the story of a young girl finding her way out of extreme family dysfunction through sex and love. I was quite virginal at the time, I should say, so of course it was partly aspirational–I wanted love, to be undone. I wanted to be the girl and the writer. I knew it was the only way out. The erotic as cure, I say somewhere else in the book. Which is also what The Lover is about: I will act out my family’s pathology and in doing so I will become someone else – I will become someone apart from the family.

Being “sensitive” in a family often becomes pathologized. The sensitive one is perceived as self-centered, or a bother, someone to tiptoe around, rather than a valued spirit. If you’re not satisfied with the bromides of grief–”your mother’s up in heaven watching you” or “She’s at peace now” then there’s something wrong with you. The result is a silencing. How do you feel about the term “designated patient?” Did you think it was accurate when the doctors described you as having that role in your family?

Yes, it was in my case. There were so many silences in our family, feelings/emotions that went unprocessed for the greater good (i.e. the functioning of the newly formed family structure). So of course it had to come out somewhere. I happened to be the one to break down, which was a way of breaking the charade.

Was it a relief when the doctors in the hospital explained it that way?

I think it was a relief–but it didn’t mean I could change right away. I was still very stuck–but there were moments of insight like this that certainly validated my experience. It was perhaps the first introduction to an idea that has stayed with me, that makes a lot of sense. and has helped me to work through certain difficulties over the years.

Do you see this role as designated patient as being also linked to what Kristeva calls the “fragile reader?” This sensitivity to writing is also what led you to Audre Lorde, who taught you to locate your own authority in your story, outside the medical model.

Yes, absolutely–I think it’s the best way to read, an active search for identification and other ways of understanding my experience. A desire and willingness to be transformed by a book.

In “Interlude 2022,” you talk about how DSM diagnoses often lead to “limiting stories, someone else’s stories.” Why do you prefer the term “madness” to “mentally ill” or even to “crazy”? Madness as a term definitely has a deeper literary resonance (as you talk about Shakespeare and Woolf using the term. I’m also thinking about Bertha Mason in Jane Eyre). Do you see distinctions between the terms madness, mentally ill (with all the acronyms and diagnoses), and crazy?

I use all of the words in different contexts. Crazy is colloquial, but can be offensive of course, and useful, too –funny or protective. I think that “mentally ill” gets overused because it has the psychopharma-medical establishment behind it. It’s pretty meaningless. So then we need more words. Depression is so vague but then we also need it, just as we need bipolar. But again, so many people are depressed and/or bipolar, according to the various DSM‘s expansive definitions. So what are we talking about, exactly? The problem is the number of defined illnesses in the DSM depends on this need for more specificity, which often justifies excessive or easy drug treatment.

Buy Committed.

I am aware that these words allow for people to get care, to have their suffering identified as something real and therefore worth attention. But as a writer, I’m always listening for the gaps–what people aren’t saying when they use these words, or what they are foreclosing.

I prefer madness because it is philosophical. It encompasses the spiritual, the seeking self, the artistic impulse, too, which can be about pushing past convention and norms, seeing through or investigating extreme emotional experiences that we are meant to absorb or curtail.

You mention madness as having a spiritual component and also about being a lapsed Catholic–and I can relate. I felt so touched when you said that you felt love there in the church, and that you felt comfort in the Confessional box. When we’re girls, the Catholic parish is the whole world, and we’re celebrated –through Communion, Confirmation, Penance–but I feel that something happens as we age into our womanhood. We feel this deep betrayal, as the burden of our bodies becomes the host of sin. We have to be modest, don’t have sex, but don’t use birth control, don’t have an abortion. This betrayal can be enough to drive us mad, yes? The confusing loss of that comfort can drive us mad, yes?

Yes, it is a terrible betrayal. And to learn later the history of sexual abuse, the mistreatment of women in the Magdalene laundries, for example–it’s horrible. To have been so deeply invested and comforted by such a sickening institution. I’ll never get over it.

In terms of madness, I always found it telling that St. Dymphna, who was abused by her father and then went mad– that SHE became the patron saint of mental illness. That says so much about mental illness as gendered, and it says a lot about the church, too. We’d rather make you a saint than face the reality of rape and sexual abuse.

The thing is, religion and that devotedness to Catholicism, which is so full of beauty and transcendence–that’s terrific training for an artist, a writer, that engagement with the extremity of emotion, of desire, of need. It’s a not an uncommon transition, away from religion and into art.

To clarify–there is madness in that desire, that need to get close to Christ, or the idea of this emaciated deathly body looming overhead–so compelling–and when this framework failed, I just didn’t know what to do–or I did know, I started reading like mad because otherwise everything is a letdown–to grow up Catholic it was as if something solid was there, something real–again, a kind of madness to believe in it, but very productive. Like many insanities!

And after you realize the betrayal, as you say in the book, “This is how you become an artist. You become true to yourself alone. You move away from what you’ve known, those received identities and opinions of youth.”

Eileen Favorite’s novel, The Heroines (Scribner), has been translated into five languages. Her essays, poems, and stories have appeared in Chicago Magazine, The Toast, Triquarterly, The Chicago Tribune, The Rumpus, Diagram, and most recently, The Manifest-Station, and others. Her essay, “On Aerial Views,” was a Notable Essay in the Best American Essays 2020. She was named a 2021 Illinois Arts Council Awardee for nonfiction. She teaches writing and literature classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. More about Eileen Favorite.