The sky was still pink with morning by the time Celia had Namid seated at the kitchen table. The floor creaked as her slippers shuffled into the laundry nook, where she pulled two clean bath towels out of last night’s dryer load.

“Would you like some coffee?” she asked as she returned to the table. Namid hadn’t shifted her position or gaze since coming inside.

She had woken up before her alarm that morning, and rather than trying to fall back asleep, she made her way down the stairs of the old family home to prepare some coffee in their grandmother’s percolator. Aside from starting the day at an earlier hour, Celia’s routine went as it usually had since she moved back home: pour two scoops of coffee grounds into the percolator, pour one scoop of bargain kibble into Trixie’s bowl, rewash Namid’s wine glass from the night before, then lean against the counter and unweave her braided hair. This morning, she looked over the blue Danish plates her great-grandmother affixed to the wall over fifty years ago. The sounds of boiling water and Trixie’s paws scuttling over the worn linoleum pulled her from the pastoral porcelain scenery and back into the kitchen. Other than the upgraded toaster, her sister’s milk frother, and ditching the landline, it probably looked the same as it did four generations ago. The natural light grew warmer, and she peeked outside the window to catch the sunrise coming over the backyard’s tree line—instead she saw her younger sister, hair drenched in an oversized T-shirt, neck craned back to stare at the sky.

Celia draped one towel over Namid’s shoulders before using the other to start drying her long, dark hair. It was late August, and she didn’t recall hearing rain last night, but Namid’s shirt, other than her shoulders or where her hair would have touched, was dry.

The percolator gurgled on the stovetop as Celia knelt to start cleaning blades of dewy grass from off her feet. Her sister’s white-knuckled hands rested on her knees.

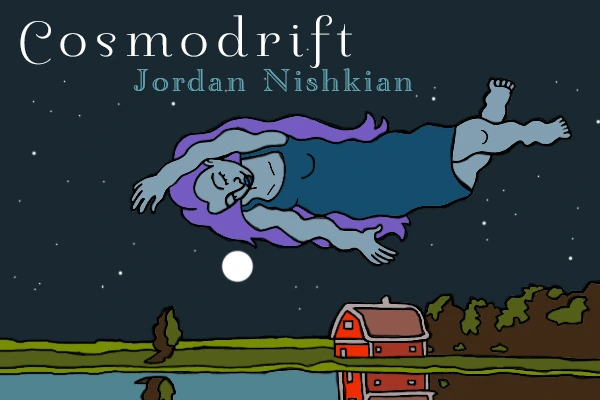

The weightlessness reminded Namid of being suspended between the floor and surface of the community pool. Tendrils of wet hair drifted around her face and the hem of her shirt fluttered around her thighs. Despite the clear summer air, goosebumps pricked her arms and legs, and small shadows danced across her skin, reacting to the azure glow outlining her body. Her hands floated upward, reaching toward the bright, faraway point that pulled her closer. Her bare feet were damp from before she left the ground.

“Namid?”

Namid’s eyes refocused and found Celia’s.

“Would you drink some coffee?”

Namid nodded as Celia left the towel, got herself to her feet, and headed for the cabinet. She took down two mugs—one a souvenir from Namid’s trip to Chicago a few years ago, and one that was so old, Celia thought it may have come with the house. She turned off the stove and poured the coffee before grabbing the milk from the fridge, careful not to lift the door off its hinges.

Namid hadn’t sleepwalked since they were teenagers, but maybe the stress about potentially selling the house was getting to her.

She studied her fingertips; they were wrinkled from her shower, but as she floated past her bathroom window, she saw the glass was clear and absent of fog. How long had she been drifting?

Celia’s spoon clanked against ceramic as she stirred in the milk. After the coffee had turned the color of sandalwood, she took a seat in her familiar chair and set the mugs onto the table. The vacant look had returned to Namid’s face.

“Coffee’s on the table,” she said.

“Oh,” Namid murmured and turned her chair to face Celia. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” she answered, watching her shift her focus to the contents of the Chicago mug. “So, do you want to talk about it?”

The next window she’d pass would be Celia’s, and she was surprised to see an amber glow radiating from her nightstand as her sister sat cross-legged on a bed covered in loose papers. Her weary hands cradled her head.

Namid looked up. Her eyes were so dark that Celia could almost see her reflection in them. She couldn’t place what was different—she didn’t look tired, but it was unusual for her to be so sedate.

“Why I was outside?”

“Probably a good start.”

Namid paused, glanced at the clock near the pantry, and thinned her lips into a remorseful smile.

Celia frowned. “What was that?”

“You’re not going to believe me.”

Namid twisted so her belly faced the earth, causing her still-wet hair to recoil and brush past her face as she looked over her one and only home.

Flickering projections of her younger selves were scattered around the property: jumping over the wooden fence that surrounded the backyard, getting a kite stuck in the ancient oak by the porch, running in and out of the kitchen door to and from the school bus or a friend’s car, storming out of Celia’s room after last night’s argument.

The projected memories faded with her smile as she noticed the chipped paint on the siding, the worn, mossy shingles on the roof, and how the oak had become choked with mistletoe and ivy.

“Why are you saying that? What’s going on?” Celia asked.

“You’re going to do your best to understand, but you won’t.”

It was 6:34 a.m. Ribbons of steam rose from their mugs as the coffee in Celia’s rippled from her shaking hands. She clamped her teeth hard, fighting the barrage of questions that scraped the backs of her teeth. She released them with an exhale and opened her hand to Namid on the table. “All I can do is tell you that I hear you and will always believe you.”

Namid folded her hand around Celia’s outstretched palm.

She was high enough now to see their neighbors’ homes and a small cluster of trees that grew between their yards and the slope of the mountain. To her left, more farmland and the dusty roads that accompanied it. To her right, the city, mimicking the starry sky with its earth-bound lights. It wasn’t so far, but she missed Celia when she moved there for college. Namid knew coming back was an adjustment for her, especially in the years of buying extension cords and all sorts of plastics to make their grandma as comfortable as possible. Their grandma’s bedroom still stored some of Celia’s things. The living room still had a space where the hospital bed used to be.

Towards the end, their grandma would murmur, eyes closed and restless, about the Great Light—“The Great Light with all the knowing.” Perhaps this is what she was talking about.

“Are you okay?” Celia broke their suspended silence.

“Yeah, I’m good.”

“Did you sleepwalk? Is this about last night?”

“No, no—” Namid paused and glanced at the clock. “Did you hear Trixie barking?”

Celia shook her head.

“She was scratching at the kitchen door, so I came down to see what she wanted. I didn’t see anything outside, but she wouldn’t budge,” Namid explained. She looked down at their terrier, who was resting her head on Celia’s feet. “I opened the door to see if it was a possum or something, and I can’t explain it, but I felt drawn to the backyard.”

Continuing her upward drift, Namid stretched and moved her arms around her. She must have been ascending for a while now, but still, her fingers were wrinkled and her shoulders were wet.

Glancing over the nearby orange grove and a semi-truck passing through, she realized that since being lifted she could only smell her jasmine conditioner. Her ears buzzed with a gentle hum.

Gusts of wind rustled the tree line. She anticipated a chill, but whatever was lifting her kept her from it: untouched, becoming the same temperature as her ambient glow. Without that luminescence, her edges would have been unrecognizable, likely to dissolve into the atmosphere.

The skepticism on Celia’s face locked up her voice.

A clicking chew interrupted their silence. Celia leaned under the table and removed Trixie’s teeth from the hotspot on her hind leg. “I’m going to have to start using that salve on her again,” she said as she sat back up. Tears welled in Namid’s eyes.

“Hey,” Celia got up and wrapped her arms around Namid’s shoulders. “What’s going on? Are you hurt?”

Namid gripped her hands on Celia’s forearm and buried her face in the crook of her elbow. This wasn’t the first time tears were had at this table: it was where she helped Namid write her first love letter, where she learned that vodka made her too maudlin, and where she and Namid shared the final peanut butter cookie from their grandma’s last batch. Celia rested her chin on her sister’s head, breathing in jasmine. She could almost sense how hard Namid was searching for an answer.

Once she could see the town on the other side of the mountain, she flipped her body upwards to acquaint herself with starlight. There was a new moon that evening, and nothing besides her surrounding glow was competing with the midnight mosaic before her. She could remember Celia pointing at certain constellations with names like Orion’s Belt and Ursa Major and Minor.

As Namid connected the dots of constellations, thin, web-like lines began to reel out of her fingers, toes, and hair follicles, branching out into different images that spanned the void in an exponential network of what could be.

Celia untwisted herself and started rubbing Namid’s arms. “We should run you a bath, you’re as cold as the room.”

She turned to head upstairs.

“Cee, wait.”

“I’m just going to get the water running—”

“Can you wait, please, for one minute?” Namid asked.

She spent hours tracing different threads of events and trying to retain what actions would lead to what timelines, surprised by how few allowed her sister to be happy. Then, when the sky began to lighten, she started to drop, lowering as the stars and their webs dissipated into twilight. Unafraid, she released her body to the pull of gravity and gave into the fall. She knew what came next.

Celia bit the inside of her cheek. “Is this about the fight?”

“I already told you it isn’t—”

“—I was thinking about it last night and I couldn’t really sleep—”

“—that’s not what this is—”

“—I didn’t handle myself well—”

“—it’s okay, but—”

“—our family doesn’t have a history of considering what I want—”

“—I saw what all our different futures look like—”

“—but I shouldn’t have called you selfish, especially ’cause I’ve never laid down boundaries—”

“—Trixie’s going to chew her leg now—”

“—Trixie, stop that—”

“—You need to sell the house—”

“—I know staying here means a lot to you, there’s just no way we can afford—”

“You need to sell the house.”

Celia halted, confused. “You’ve been pushing back on this for months.”

Namid nodded. “I was afraid of change. I like our life, it’s easy—”

“For you.”

“For me.”

Before sunrise swallowed the gentle light, it eased her onto the ground. Upon soft impact, she crouched, allowing her fingers and toes to grip the damp soil and the sharp edges of the grass. She took her time to stand, noticing the connections between her bones and the weight of her wet hair on her shoulders. The warm air was slick against her cold skin—even in its stillness, she could feel everything. Breathing in the familiar scent of geosmin, she tipped her head back, looking once more to the stars.

“Now you can sell it in a few months and someone will flip it into a quaint rental,” Namid continued, looking over the row of trinkets and tchotchkes that hadn’t moved from their spots on top of the cupboards in decades. “You’ll move to the city to live in your own condo, I’ll move in with Mark—”

“Who’s Mark?”

“My boyfriend—”

“You have a boyfriend?”

“Not for another few weeks.” Namid held up her hand. “We’ll have opposite schedules because of our jobs and it’ll be hard to get together to hang out, so we’ll just stop trying and drift apart.”

Celia crouched down. “We will not drift apart.”

Namid’s eyes stared past Celia’s face and out the window. “We will. But we eventually come back together in this one,” she murmured and gave her sister’s hand a squeeze before getting up from her chair. The towel on her shoulders dropped and joined the other on the floor. “We end up okay in all of them, I’m just going to miss you.”

Namid touched the top of Celia’s head as she stepped toward the stairs. “I’m going to take that bath now and warm up. Want to go for a bike ride later?”

“Um, sure,” Celia answered. “That sounds nice.”

She watched Namid climb the flight of stairs, holding her breath until she heard the familiar squeal of the faucet and the rattle of pipes. Exhaling, she picked up the two damp towels, examining the rose-tinted sky as she made her way back to the laundry nook.

Jordan Nishkian is an Armenian-Portuguese writer based in California. Her prose and poetry explore themes of duality and have been featured in national and international publications. She is the Editor-in-Chief of Mythos literary magazine and author of Kindred, a novella.