Three friends met at a house in Katy, Houston. They had been classmates at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology. One of them, Bappi, was a businessman in Bangladesh and had come to America to attend his nephew’s wedding in Texas. He had called up his friends, wanting to meet them before he returned home. The other two were successful engineers in oil and gas. The house in Cinco Ranch belonged to one of the successful engineers, Murad, who was slight of build, lithe, with a full head of jet-black hair. He dressed crisply in the most respected name brands (his wife had worked at various upscale department stores at the mall, where she had earned excellent knowledge of how men should dress), a Polo Ralph Lauren shirt, woolen black pants, and cashmere socks. He was shrewd and well spoken, and he knew how to network smoothly at work and speak back aggressively when colleagues challenged him. Without these skills, an engineer from Bangladesh could not have made it in the industry. The third friend Jawad was even more successful than Murad. He had recently moved to Fullshear, where the lots and houses were bigger than in Cinco Ranch.

The three friends had just collected their food laid out in the dining room by Murad’s wife and carried their heaped plates back to the drawing room.

“So, Bappi, how is business in Bangladesh?” Murad asked, settling on the expensive, white leather couch and digging into the delicious goat biriyani his wife had cooked.

“It’s going well, it’s going well,” Bappi chirped, but to the other two it did not appear that things were going well for their Bangladeshi friend.

Bappi’s face was bloated and punched up, sitting atop a thickened neck. His hairline had receded to the very back of his skull, his eyes were sunken, and his skin was dry and scaly, like the skin of a man on his deathbed, poisoned from the car exhaust and particulate matter he inhaled daily on the streets of Dhaka. Murad and Jawad had often spoken to each other about how their friends in Bangladesh looked so much older than them, like corpses almost, and here was Bappi as living proof of their words. He looked like he was on the brink of a heart attack or a stroke.

“I’ve heard that it’s difficult to do business in Bangladesh with all the corruption going on,” Jawad said. “I could never work in a corrupt environment like that.” He shook his head to emphasize his disgust of people who did business in Bangladesh.

“It’s not so bad,” Bappi mumbled between bites. Swiveling his thick neck, he admired the palatial high ceiling of the living room and the grand staircase in front, leading to a theatrical balcony upstairs. The square, glass-top center table in front of the sofas looked like it had cost a fortune. Massive art pieces rested on recessed wall shelves and on tops of various tables, their sizes alone declaring their value.

“Do you have to pay bribes to get things done over there?” Murad asked, pressing the issue, looking Bappi straight in the eye. He was a talkative fellow who liked to have things out in the open.

“Yes, you have to, a little bit, but it’s okay,” Bappi said, shifting his gaze and changing his position on the sofa. His drooping eyelids, which gave his eyes the appearance of being hooded, dropped a little lower. He looked helpless and slightly frightened, as if he felt trapped by the questions.

“Apparently, you can’t move an inch in that place without bribing!” Jawad laughed. “Anyone who lives like that, engaging in that kind of corruption every day, can have no soul left.”

Bappi nodded, having no answer to these accusations. As the owner of two garment factories, his days involved as much technical work—getting new work orders, visiting factories, and looking over financial statements—as sending gifts to ministers’ houses or making calls for a government official’s daughter to be admitted to a prestigious high school. It was all about doing favors and oiling the machine to keep the actual machinery in his factories running.

Murad’s wife appeared in the doorway, dressed in slim slacks and a peasant top. She had a small, delicate face, like a young teenager. “Bappi Bhai, is the food okay?” she asked in a sweet voice. “Cooking for a person from Bangladesh, I’m nervous.”

“It’s good, very good,” Bappi replied, smiling nervously, intimidated by his friend’s modern wife. His own wife was twice his size and could hardly move because of complications from gout. She had to use a step stool to climb into their car on the few occasions she ventured out of the house.

“We can’t compete with food from Bangladesh, Bhabi,” Jawad said with a derisive laugh, addressing Murad’s wife. “Without all the contaminants they put in the food there, food is not tasty.”

“Ha ha, that is true!” Murad’s wife laughed heartily. “But I tried my best. Murad bought fresh goat meat from the farm we have here. I made the ghee myself at home from organic milk. Bappi Bhai, all the ingredients in the food are fresh and organic.”

“It’s very good, very good,” Bappi said again self-consciously.

When Murad’s wife had left, the three friends talked about common friends— who was doing what, their old days at university, and the trips Murad and Jawad had taken to Bangladesh.

“You understand, friend, the traffic in Bangladesh drove me crazy,” Murad confided in Bappi.

“It’s better now. How long ago did you visit?” Bappi asked sheepishly, chewing on the organic goat meat. He had to admit that it tasted better than the food he usually ate, even at the most expensive restaurants in Dhaka, where the curry was cooked in old oil. He always suffered from a stomachache after eating out, and sometimes he even had food poisoning.

“About five years . . . ,” Murad said.

“It’s better now,” Bappi insisted in a sure voice, “they put that over-bridge in and now the traffic goes faster.”

At these words, Jawad shook his head in disgust. He was taller than the other two, and he had a handsome, chiseled face and a body rippling with muscles. Unlike Murad, who had risen in his profession through his friendliness and his ability to socialize, Jawad had made it through sheer smarts. He refused to take any nonsense from anyone.

“Where, bhai, I didn’t see the traffic move any faster,” Jawad challenged Bappi now, twisting his thin lips. “I was there just this summer. From what I saw, now there is a traffic jam on the bridge and on the road too. It took me three hours to go from Baridhara to Gulshan. Unbelievable!”

Bappi jumped a little at his friend’s statement of the harsh facts. He had no defense in response. He bent his head and ate in silence, studying Jawad’s tight, angry face. In Bangladesh, Bappi remembered, Jawad used to wear thick, dusty glasses. But now, there were no glasses to be seen. Bappi wanted to ask if Jawad wore contact lenses now.

“How long does it take you to drive to work, Bappi?” Murad asked.

“Uh, if I leave at nine in the morning, about two hours,” Bappi answered.

“Two hours! Two hours! And yourfactory is just in Mirpur, isn’t it?” Murad said, leaning forward with sympathy. “And your home is in Dhanmondi? It shouldn’t take more than twenty minutes, tops. Unbelievable. This is unconscionable. These leaders of Bangladesh couldn’t even solve a simple problem like traffic jam.”

“None of that for me, no sir,” Jawad said. “Do you know how far I drive to work every day? Thirty-five miles exactly. And it just takes me over half an hour to get home. Then I go out and play squash at the gym.”

Bappi nodded in self defeat, looking down dully at his misshaped body, which he had let go to waste in the race to make money and be successful. In contrast to the idyllic picture his American friend had painted of his life, Bappi’s every day consisted of hours spent sitting in traffic and running around government offices to bribe so-and-so to get a simple piece of work done. When he returned home, there was nothing to do but sit in front of the TV and eat oily snacks.

Taking advantage of a lull in the conversation, Bappi looked around the dimly lit drawing room at the surround-sound speakers and the plasma TV mounted on the wall, all things he admired and envied. He sucked an oily finger, and Murad quickly fished out a napkin from under a paper weight shaped like a swan trapped inside a glass vessel and handed it to Bappi before he could wipe his hand on the sofa.

“Thank you,” Bappi said, taking the napkin.

“Imagine kids having to sit in traffic that long just to go to school,” Murad said, sitting back down. “My kids just go to the school next door. Their mother walks them there. Best school in the country.”

Bappi had paid one lakh taka to get his only son admitted to a good private school in Dhaka. He could brag about that, but then he remembered that his son had developed asthma from sitting in traffic every day.

“Honestly, friend, I settled in America for the children,” Murad said philosophically, locking his arms behind his head. He sat with his legs planted apart and stretched out in front, in a mood of deep relaxation. “Education is free and good in this country. The children learn so much. The math they do would shame us.”

“The education system in Bangladesh is totally messed up!” Jawad agreed. “Even the wealthy people in Bangladesh are sending their children abroad to study. Hey, Bappi, is it true that the wealthy don’t even vacation in Bangladesh? They just fly to Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand at the slightest opportunity? It’s like they can’t stand to be in the country any longer than necessary! Do you vacation abroad as well, Bappi?” Jawad smiled, his lips curling, showing his pink gums.

“Actually, my father just passed away recently . . . ,” Bappy said.

“Oh, I’m sorry to hear that,” Murad said warmly.

“Thank you, friend. My father had some lands in his village, in Sylhet, and a house,” Bappi continued. “A caretaker used to live there and send us crops from the agricultural lands. After my father died, I tore down the old structure and built a brick house,” Bappi said.

“That engineering degree came in useful after all then!” Jawad said in a mocking voice, making a dig at the fact that Bappi was just a businessman, whereas Murad and Jawad were working as professional engineers at the world’s preeminent multinational companies.

Bappi had been a better student than the other two at the engineering university. But they had had big dreams. They had dreamed of coming to America for their graduate studies and settling abroad, working for big companies, and living in grand houses. By the time of the graduation ceremony, about half the engineering class at their university had already left for higher studies in America, following their dreams. When they called the roll for people to receive their degree certificates at the convocation, half the auditorium was empty! One night, Jawad and Murad had sat in this very living room talking about the difference between successful engineering graduates like themselves and those who hadn’t made it. They had specifically mentioned Bappi as an example of a good student who had fallen by the wayside. The problem, they had decided, was that these people who had not made anything of themselves had not dreamed of big things. They had no vision, no ambition.

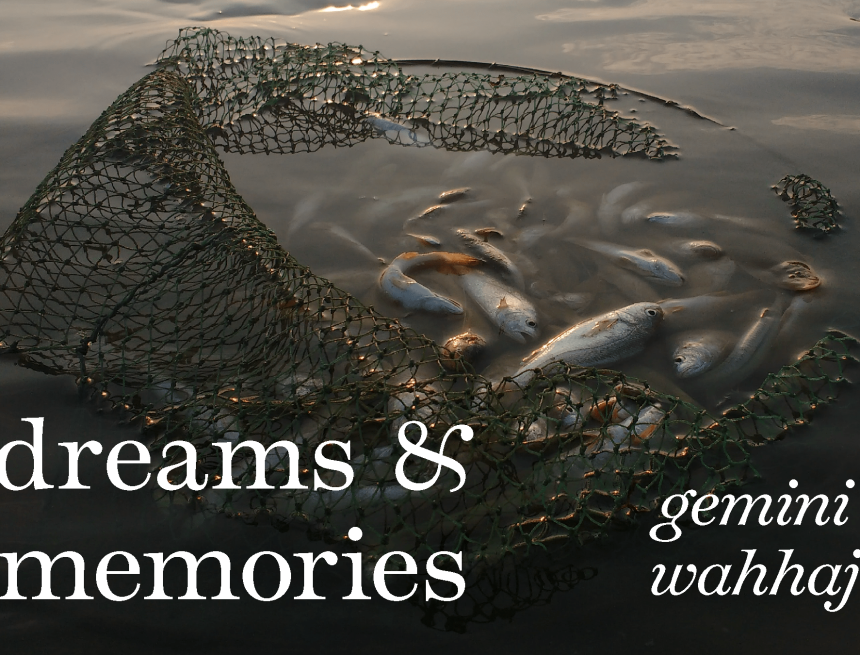

“Yes, my degree did come in handy!” Bappi laughed sheepishly along with his friends at this dig at himself. “After fixing up the house, I’ve started to visit my father’s village house on most weekends,” he continued. “On Friday, after work, I pack up the family, and we drive out to Sylhet. My father’s home was in Taherpur in Sunamganj, near the border with India. It’s low haor land, with the fields submerged in water, and so fertile. During the floods, the waterbody stretches from end to end, like a great, big river. I take my fishing nets to the water and my son and I sit for hours fishing. Sometimes, we fish till dark. The evening azaan from the nearby mosque sounds over the waters and moonlight plays on its surface. You can smell the salty water. There are other fishermen standing on the banks or in boats in the water, crying out as they haul their fish. Sometimes, we take out a boat on the water ourselves. We can see the Khasiya mountains far away. Over our heads, there are so many multicolored migratory birds flying. At times like this, I feel connected to my father and his father and all of my history.”

Bappi’s two friends frowned, shutting their eyes slightly. Something seemed to pass over them. As their friend talked, suddenly they could taste the salty morning air and hear the rustle of birds and birdcalls from their own childhoods. Old memories stirred inside them, things they had not thought about in decades while driving inside their solid, metallic cars on the highway between Katy and downtown. They shook their heads to clear the memories.

Perhaps they were comparing themselves to Bappi, trying to prove to themselves that their lives were better. At the mention of the prayer from the mosque, they told themselves that they attended the prayers at their grand mosque in Katy, which had been built by donations from wealthy immigrant doctors and engineers. At the mention of fish, they comforted themselves that the fish in Bangladesh were polluted, and that they could buy the biggest ocean fish in Houston. In all aspects, they had fared better than their friend by coming to America.

“Sometimes, we catch so many small, silver puti fish,” Bappi continued in a far-off, dreamy voice. “My son and I sit on top of the muddy water and we disentangle the fish from the net, one by one. All around us, there are lily pads and water hyacinth and the simple slop-slop sounds of water. Then we walk with our treasures stashed in a tin pot through the morning fog, stepping through the mud and rice paddy. I tell you, my friend, a few hours spent in my father’s village, and I feel like I’m in heaven!”

Their Bangladeshi friend now had an expression of unearthly delight on his face, as if he were dreaming a dream rather than sitting in an elegant drawing room in the oil-rich city of Houston.

“Well, well.” Murad laughed a little shakily, “Look, my wife has returned with sweets. Her homemade rosgollas are the talk of Houston.”

“Eat, Bappi Bhai,” Murad’s wife said, bending down to place a heavy bowl of white sweets swimming in syrup, with three smaller bowls and some dessert spoons on the glass table.

“Thank you,” Bappi said, acknowledging the sweets she served him, but now his eyes were far away.

“Be careful with the sweets. You’re getting fat, my friend,” Jawad said with sudden viciousness. “And your hairline is receding too!” he cried more loudly. “Perhaps eating all those fish did something to your hair!” Something in Bappi’s words had shaken Jawad and distorted his reality. He blinked his eyes again and again, trying to restore his vision.

Murad gulped down his wife’s famous sweets, then stood up and turned the lights up to full brightness. “It’s getting late, friends. I have to work the next day,” he said abruptly.

“Me too, me too!” Jawad said, jumping up hastily from the sofa. “I have a long drive home. Idle chat is nice, but one has work to do. It’s not like in Bangladesh, where no one shows up to work on time and everyone leaves for lunch halfway through the day. I bet in Bangladesh, you guys have so much time that everyone is always going fishing!”

Bappi stood up too. “Thank you for seeing me. It was good to see you both. Thank you for the lovely dinner . . .” He almost upset a large, painted vase and righted it nervously with both hands.

“No problem,” his two friends said, hurrying him toward the door, trying to get away from him and the storm he had aroused in them, as if he could topple all their happiness.

“Come visit me in Bangladesh,” Bappi said at the door.

“Sure, sure,” his friends said, averting their eyes as they encouraged him out.

Bappi said goodbye again, standing under the night sky outside, then he walked to his rental car, lowering his torso slowly into the driver’s seat, as the space inside was too tight for his corpulent frame. Jawad marched past Bappi to his new Lexus SUV, striding easily in his long legs, whistling jauntily and swinging his key, but his sleek, black car only reminded him of the long drive to work the next day and the next and the day after that. The third friend, Murad, shut the door of his house, going back inside to the dark cocoon of his carefully constructed life abroad.

Gemini Wahhaj is associate professor of English at the Lone Star College in Houston. She has a PhD in creative writing from the University of Houston. Her fiction has appeared in Granta, Zone 3, Northwest Review, Cimarron Review, the Carolina Quarterly, Crab Orchard Review, Chattahoochee Review, Apogee, Silk Road, Night Train, Cleaver, and Concho River Review, among others. She has received the James A. Michener award for fiction at the University of Houston, an honorable mention in the Atlantic student writer contest 2006, an honorable mention in Glimmer Train fiction contest Spring 2005, Zone 3 Literary Awards winner in 2021, and the prize for best undergraduate fiction at the University of Pennsylvania, judged by Philip Roth. An excerpt of her Young Adult manuscript The Girl Next Door was published in Exotic Gothic Volume 5 featuring Joyce Carol Oates. She was senior editor at Feminist Economics and staff writer at the Daily Star in Bangladesh. Forthcoming publications include Scoundrel Time, Chicago Quarterly Review, Arkansas Review, Allium, Valley Voices, and the Raven’s Perch. She is the editor of the magazine Cat 5 Review.