By Kate Wisel

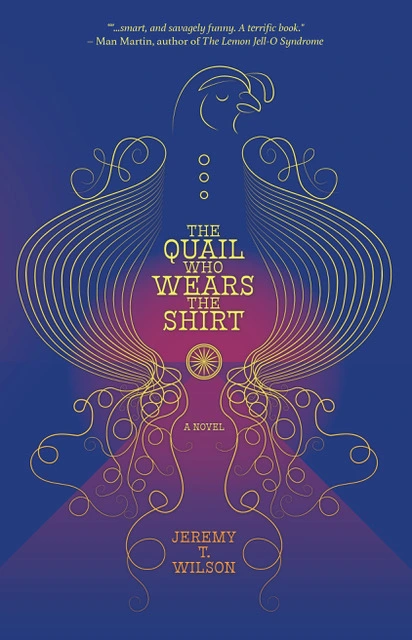

On the phone, for reasons we no longer understand, my friend and I forgo the usual hello for a grave incantation, “There’s been an accident.” What follows is invariably more interesting. That’s how Jeremy Wilson’s tragicomic novel, The Quail Who Wears the Shirt, begins: with an epic accident. Livewire Lee, family man (with a question mark) boss of a bustling produce store, whose hashtag may as well be #MeFirst, drives his pick-up a few beers deep and runs over townie Valentine, a quail-person—trust it. In the town of Charity, Georgia, regular people are mysteriously becoming quails, a reality instantly accepted thanks to Wilson’s razor-sharp satire and narrative instincts. What proceeds is a high-octane series of unfortunate events, reminiscent of Good Time by Benny Safdie, a film that nose-dives and backfires as it follows the reckless choices of two misguided brothers. But unlike the brothers, Lee has no accomplice. His side-chick’s outgrown him, his wife’s on the verge of leaving him, he’s drowned his phone and lost his kids. But alone is where we need him to be, as tantamount to Lee’s desire for adrenalized, ego-driven pleasure is the need for a spiritual intervention.

And spiritual it is. Wilson’s rendering of the quail-people is a strange form of atavism, against our ADHD-driven culture there is a deep desire for freedom and simplicity. With hilarity and originality, Wilson circles around those uncomfortable truths about neoliberalism and the high-fructose lie that is the American Dream—how ascension is only available to the privileged. There is a moment when Lee comes to his senses and cooks a homemade onion pie, a gesture of kindness for a bereaved neighbor. The pie’s a symbol of community, of gestures and institutions that have been stripped from the American experience to our detriment. The Quail Who Wears the Shirt shows us what we reach for, and how, like Lee says, we search for answers (on the internet) without the right questions.

A word about Jeremy—you can find him in the back row at readings in Chicago, quietly, consistently supporting other authors, asking funny, thoughtful questions. And sometimes, he even brings pie.

Tell me about meeting Lee as a character. When did you first conceive of him? Or was it Lee’s world you met first? Or should I say, the world that is becoming less and less Lee’s?

I wrote a short story a long time ago about a guy who shows up to work one day and finds out a coworker has died. He didn’t really know this coworker very well, but he feels bad, so he tries to find out more about him, and what he finds out is that the dude was an asshole. The story obviously wasn’t that great, but for some reason, the seed stayed planted. I guess Lee finally arrived when I allowed myself the freedom to write from the voice of someone I wouldn’t necessarily agree with. I’m intrigued by artists and musicians who use persona to explore aspects of their art. Josh Tillman becomes Father John Misty. Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds become Grinderman. Garth Brooks becomes Chris Gaines. (Yeah, okay, that last one was really weird.) This allows for a more honest exploration of topics, obsessions and questions that might seem taboo, or beyond the pale of polite society, or simply unexpected. Plus, as we all remember every Halloween, it’s fun to dress up as somebody else, even if that person is a monster.

This is true. In speaking about Disney’s Medusa, a friend told her daughter that you could be a monster and still be good, which I found so valuable. We’re quick to call school shooters monsters when their actions are often the culmination of our culture’s failure to look at them. If we instead asked what happened to them, we’d have to ask what happened to ourselves, how we got here. Not that Lee is at that level, he engages in the common man’s evil, but you look at him so well in this book, the parts of him that blur certain paradigms of morality. Speaking of Lee and his world, Georgia is such a highly specific and charged place. What’s your connection to it?

I’m glad that you say “that in looking at them we can also acknowledge parts of ourselves.” I’m really hoping that’s the experience readers have with Lee. Anyway, I moved to Perry, Georgia when I was in eighth grade. My parents grew up there and wanted to move back, so we did, and my immediate family as well as most of my nieces and nephews still live in Georgia. And even though I’ve lived in the Midwest now for twenty plus years, it’s hard to shake the influence of the South in general and Georgia in particular. Not that I’m trying to shake it. I love Georgia, and I miss it, which is probably why it’s the setting for most of my writing.

The quail-people appear on the fringes of Charity, in hushed conversation at pawn shops and dive bars. They’re blamed for crime, laziness, and deviant activity. These narratives designed to cast them as sub-human make it easier to treat them like they don’t matter, or to kill them. Their demonization reminded me of the War on Drugs and how drug epidemics are crafted by our government as systems of racial and social control, to criminalize minorities. Beyond thinking of the quails in terms of being a classically marginalized population, it got me thinking about fear in general towards the unknown, how we question if AI is a pragmatic tool or a salient creature. How alien narratives are fear-based when it’s equally possible that aliens could be here to save us. What got you interested in the idea of fear towards change, transformation and becoming?

I can’t think of any way around this cliché so I’ll just say it: the only constant is change, right? But that doesn’t mean we’re any good at accepting it. We fear change, and this fear is also a fear of the unknown, like you mention. And a fear of the unknown leads to a host of problems, because for some reason we default to change being negative (your alien example). One of the things that fiction can do is explore these fears from a safe distance, speculate on what might happen when things change. Maybe that change isn’t good or bad, but simply something new. This is of particular interest to me with respect to the body. Our bodies are constantly changing, which can be scary. But if we can ignore all the commercials telling us how awful and scary our changing bodies are, then this can be beautiful. Trees don’t worry when their leaves change colors (you can see why I’m not a poet). So what if we turn into quails? What possibilities does that open up? What insights have we not yet discovered? Lee wants to uphold the status quo, his “known universe,” and that’s usually pretty easy for somebody like him. The only way to challenge him is through the physical, the visceral; change that he can both see and feel. Change that he must embody.

Speaking of this, Lee says of his father: “He was a man who was always looking back with fond nostalgia to a falsely idealized past, or looking forward to a future some asshole promised him would be better.” Lee talks about legacy, about narratives being passed down generations, especially in the context of the South, but can’t see his own involvement in this. Later, Lee describes an earlier vision of his life: “a big white house with shutters, a bunch of beautiful kids, girls growing up to be cheerleaders with bows in their hair, the boys football stars, all of them ruling the known universe.” Can you talk more about this “known universe?”

Without being fully aware of it, Lee is describing the limitations of his known universe. The description doesn’t simply illuminate the limits to Lee’s imagination, but shows how that lack of imagination also inhibits others. A house can only be one way. A girl can only be one way. A boy can only be one way. Any deviation from the norm is treated like a virus, something to get rid of before it spreads. It’s easy for men like Lee—white, straight, well-off—to perpetuate this known universe because they are the ones with the most power. Lee has all the advantages, even if he can’t see it that way. In the simplest terms, the whole novel might be seen as one man finally confronting all that he’s taken for granted.

I like that. Do you think writers have more imagination, that it’s reflexive, or do you think we all have to practice imagination the way compassion must be practiced and not just felt?

I’m not sure writers have more imagination. Maybe we just refuse to grow up and let our imaginations die. I teach at a public arts high school, and sometimes I get asked how our creative writing curriculum will serve our students once they graduate. It’s a fair question, I guess, but what they really want to know is how will writing stories and poems be useful. Conversations about the utility of art are exhausting. What if the practice of writing (or any art) is simply about cultivating and nourishing our imaginations? Sparking our creativity? Engaging our curiosity? Sustaining our sense of play? These abstractions are difficult to monetize, so as we get older we often give them up or are forced to give them up. But all writers are still children.

Lee’s employee A.J. is young but a lot more sensible than Lee. He’s forward-thinking, working overtime to cook unsolicited but inspired farm-to-table recipes, to which Lee sees dollar signs. He wears make-up in solidarity with his fellow quail employee. He’s the future Lee fears. I found A.J. essential to the inherent energy of this book, and I guess a diametrical opposite could also be called a foil. Do you think foils are necessary for narratives?

A foil was necessary for this narrative, for sure. For one thing, A.J. helps situate the story as satire. Having a character who opposes Lee helps highlight the flaws in much of Lee’s worldview. And as you said, A.J. is representative of the future that Lee fears. We’ve been talking about change, and the older we get it’s hard sometimes not to see change as a threat. A.J. poses no threat; it’s simply change that Lee is afraid of. And A.J. is his own person. He does not define himself in relationship to Lee, which is why when he calls Lee “boss” Lee hears it as sarcastic and asks him to stop. Nobody is A.J.’s boss. A world of employees wearing their hair like they want, getting creative on the job and genuinely expressing themselves worries Lee because he can’t see himself in that future. I use this worry as a source of humor, but it’s also problematic when someone can’t imagine a future with them in it.

Every character in this book, down to Lee’s ticked-off wife and clueless father-in-law, feels so fully realized, yet entirely distinct. Tolstoy said that if you’re writing good fiction, you are every character. Do you find that’s true?

Absolutely. Who am I to argue with Tolstoy?

I think “Master and Man” could have been two pages shorter…

Yeah, that’s probably right. But if you are ever somewhere that’s unbearably hot, may you be blessed to have a copy of that story. Instant winter.

Conversely, I won’t make a joke about burning Tolstoy for kindling. But your chapters were the perfect length and shot arrows into later pages. For instance, Lee has many overwhelming itches that he can’t scratch, but one is very real and literal. It stems from a car accident that launches into motion some reverberating calamities. The idea of the itch reminded me of Etgar Keret’s “Unzipping.” Have you written magical realism before? Or is magical realism simply becoming real?

I’m probably going to sound like a pretentious jerk (if I haven’t already!), but I like the terms fabulism or speculative fiction better. I don’t think magical realism should be separated from its origins so liberally, as if the culture, heritage, and history surrounding its creation are transferable to any and all cultures, heritages, and histories. This isn’t about appropriation, but about the dilution of the definition. That said, I do think there are elements of magical realism in Southern culture. One example: there are porch ceilings painted a shade of light blue all across the South. I think this originated with the Gullah, but the color is called “haint blue” and it keeps the haints from getting in your house. Speculative elements usually find their way into my writing because I get bored. I thought for the longest time that if I wanted to be a serious writer, I had to write slow, sad, domestic stories about people drinking too much gin and getting irrationally angry about the way their spouse folds napkins. I want to be surprised when I’m writing, and often that surprise comes from my subconscious, and what comes from there is often weird, so the speculative elements in my fiction are not so much a result of a decision I’m making but a result of my process.

I loved the dream Lee has in which he’s forced to recount moments of heartbreak as he loses parts of his body. It reminded me that life is a zero-sum game and that we will all exit as losers of some kind. It also reminded me of the quail people in that they’d lost the physical parts of themselves that had made them human, though birds are symbols of beauty and freedom. In the Buddhist sense, it seems some part of Lee needs to die in order to be liberated or reborn. Maybe it’s another way of saying his task is to evolve. What prompted you to incorporate this dream into the book?

I agree that some part of Lee needs to die, in order for him to evolve. The only way to get to that part of him is through physical transformation. More or less this is what’s happening in the dream and in reality. In this instance, the dream is also a kind of haunting, as Valentine and Lee’s father are both back from the dead to try and tell him something he’s having trouble hearing, namely that he’s got a real problem when it comes to love. In writing workshops, I often heard you should never include a dream in a story. The point is well taken. Dreams lack stakes, and stakes are crucial to fiction. But this maxim assumes we can separate dreams and reality easily, and I’m not so sure that’s always the case. I like to try to make a thing work in my fiction that somebody else might say is a bad idea. Does a dream work here? I don’t know, but without it, where would I get the title for my book?

The book is roving with ideas about the material world and its limitations. There’s the interstate that saved Charity, the fancy ice machine Lee prides himself on, and all the fix-your-life gimmicks that make up late capitalism. I think the best books point towards a frightening future but also provoke ideas about alternatives. Your satire on modernity was brilliant, and I loved how far-reaching and profound it was to imagine what lay ahead for Lee. What are your feelings about the possible futures this book illuminates for us?

Whatever the future holds I bet it’ll be weird! I mean, think about Covid. Sure, there were some who predicted a pandemic was coming and we wouldn’t be ready, but the specifics of that—all of us wiping down our groceries with alcohol, fighting over masks and vaccines, eating outdoors in bubbles—nobody could’ve guessed. Reality will always outweird our imaginations. As far as the possible future that the book illuminates, well, I’m afraid people will always find reasons to hate. But that’s even more reason to spread as much love as we can while we’re here.

Kate Wisel is the author of Driving in Cars with Homeless Men, winner of the 2019 Drue Heinz Literature Prize, selected by Min Jin Lee. Her fiction can be found in places that include Prairie Schooner, Gulf Coast, Tin House, Adroit Journal, The Best Small Fictions 2019, Redivider (as winner of the Beacon Street Prize), W.W. Norton’s Flash Fiction America and elsewhere. She was a Carol Houck fiction fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is also a screenwriter in the Writers Guild of America. Find out more about Kate Wisel HERE.

Jeremy T. Wilson is the author of the novel The Quail Who Wears the Shirt and the short story collection Adult Teeth. He is a former winner of the Chicago Tribune’s Nelson Algren Award for short fiction and the Hessman Trophy, presented by legendary Principal Durward U. Hessman to the fifth grade student who could eat the most corn. His work has appeared in The Carolina Quarterly, The Florida Review, Jet Fuel Review, The Masters Review, Sonora Review, Third Coast, The Best Small Fictions 2020, and other publications. He prefers pie over cake, waffles over pancakes, and R.E.M. over U2. He teaches creative writing at The Chicago High School for the Arts and lives in Evanston, Illinois.Find out more about Jeremy Wilson HERE.