I. The Pretty New Nurse From Pediatrics

I’m standing behind my wife in the cafeteria line at St. Mary’s. Except she’s not my wife, not yet. Right now, she’s just the P.N.N.F.P. On her tray she’s got two Jell-O cubes in a bowl. I breathe deep and stutter twice before I’m able to spit out, “Is that all you’re going to eat?!”

When she looks up, I want so bad to lick my hand, palm back this hair, and tell her that the Jell-O cubes match her green eyes. The skin on her cheeks is Wonderbread, like it’s never been hit by anything but air. Her only blemish is a tiny circular scar near the top of her forehead. She’s got charcoal slashes for eyebrows, a hatchet nose, and no chin. She doesn’t wear makeup or perfume, but still, she smells good. It makes me nervous to be this close to a musky-smelling woman, and then an actual thud – my heart – shakes my ribcage, and I realize that our meeting is the best coincidence!

We’ll hit the highway doing ninety-five, the back of the Econoline screaming with the Crime Babies of the Crime Crib. I didn’t know that I’d need, want, or meet a beautiful sidekick, but I’m rearranging the plan to fit her in. At the rest stops, we’ll make love in the front captain’s chair, then take turns pumping gas and bottle-feeding those money-grabbing babies, to make sure they aren’t getting any ideas about crying too loud. I’ll break out my roll of dimes and call Dad at The Home, where he’ll have his own personal nurse (just like I will), his own private room with a couch, a TV, a bathroom – almost everything a real home has – so he’ll never for one minute believe he’s in a hospital.

My pretty nurse (her name tag: Rhonda) is wearing a cobweb smile. She’s pondering something important – probably a guy she used to know, a guy who looks like me, a guy she loved, hated, or couldn’t care less about. She keeps reading my feet, giving me nothing but that flimsy smile. She might want to stab my neck with a fork. She might want to plant a kiss on my lips. She might want to grab my hand and force me to point to the exact spot where my lazy left eye is focusing. (No one can tell which eye I’m looking with. FYI, it’s both.)

I nod at her tray and say, “Not much for a growing woman.”

She growls, “Some people don’t need much.”

She doesn’t sound annoyed, just burned. She’s a car engine that wants oil.

II. What Nobody Knows

I’ve handled so much poop in the last three years (on and off the job) that it’s no more unpleasant than picking up a penny from the sidewalk. The bad stuff is the stuff that can’t be picked up, and this is what Dad makes in the last couple months. Yesterday, though, from the supply closet I stole a box of jumbo panty liner pads meant to catch uterus blood after a baby comes out, so now I slide these into Dad’s briefs, which I hope might help with laundry expenses.

Dad doesn’t recognize a toothbrush, and he can’t dress himself. He also can’t dress a toothbrush and doesn’t recognize himself. Quick flashes maybe once or twice a week are the exception, and during these he barks, “I’m not a goddamn baby, Travis!” in a tone that understands everything and tells me that I’m embarrassing him by stripping off his jeans for a bath. These flashes hurt the most. Real Dad appears, and I see a message in his eyes – that he appreciates what I’ve been doing, that he wishes it could be different, but that some things are inevitable. I see this in a five-second span. Then Real Dad vanishes and I wonder if it was all in my head, because he turns and begs the towel rack to let him pitch the last two innings (he played baseball in high school.)

I don’t know how old Dad is, and there’s no one around to tell me. In the ‘70s and ‘80s he was a Dodge truck. In the early ’90s after I graduated high school, he started showing the first signs of the Alzheimer’s (although he never got diagnosed), and now, ten years later, he’s a stripped Nova. He weighs 122 pounds, down from 193. His legs are cornstalks. Without my shoulder, he can’t get out of bed. If there was a God, like Mom believes, Dad wouldn’t be living anywhere anymore, but at least Dad’s in the best place, which is his own place, which is our two-bedroom apartment, mine and his.

He hates hospitals like I do and made me promise when I was only seven that I would kidnap him or euthanize him if he ever got hospitalized. I remember asking, “Even if you only get your tonsils taken out?” He nodded with a serious face, but there was a spark in his eye, and I understood that he was joking, but also that the joke wasn’t really a joke.

When I was eight, Dad sliced up the bottom of his foot by stepping on a sharp bone while swimming in a channel. He sutured himself with fishing line. When I was nine, he caught pneumonia and spent twenty days at home, refusing to go to the doctor. A year later, a pipe exploded at the caulking-glue factory where he worked, and he got second-degree scalding on the backs of his thighs. For four weeks he was on his stomach, swearing so loud I thought he’d break the windows. He ignored my mom’s “Stop being a jackass and go to the hospital” (by then her shit just bounced off of him), and once a day I scrubbed away the dead skin with a Brill-o pad and told him I was proud, that I didn’t care that he wasn’t getting “workman’s cop,” and that he was the strongest man in the world.

Mom’s been giving tours of volcanoes in Hawaii since I was eleven, which is when she left me and Dad. She only meant to leave Dad, but I told her lawyer and the judge (I couldn’t make myself look at her face) that no matter what, I wouldn’t live with her. I like to imagine Mom leading a gang of tourists around the rim of Mt. Kilauea. One hand holds her hair in place while the other points at the big hole behind her: “You don’t want to put this lava in a lamp.”

Mom hates me and Dad so much that the last time I talked to her, which was two days ago (and before that eighteen months ago, and before that three years), she said, “Your father deserves everything he’s getting. Whoremongers and adulterers will be judged.”

I wanted to whack the receiver on the table until it shattered so I could bake the shards into Betty Crocker cupcakes, mail them to her, and make her choke.

Instead I told her, “It’s a shame you feel that way,” and asked if she would send money for cigarettes and other necessities. She agreed to wire cash (after I promised that Dad wouldn’t get a dime of it), made a big deal out of telling me how quickly she’d get to the Western Union (“How’s $1,000? Is that enough? I’m putting on my sneakers this minute!”), and basically pretended she’s got a reborn pocketbook to match her reborn Christian heart. Same old routine. She won’t send anything but prayers.

When I unlock the bedroom door, Dad sits up with bugging eyes and tries to bash me with the bedside lamp. I take the lamp from his hands and set it on the floor. He’s not strong. I settle him down, cover him with a blanket. I tell him stories of things we did together, like grilling brats and corn cobs in Riverside Park, having a good laugh after buying a “boner” for our fishing trip from the blushing old lady at Ace Hardware, blasting M-80s in front of our house on Gratiot, toasting frozen pizzas in the iron 1940s oven that I called Jabba the Hot when I was small.

Dad stares across the room at things I don’t see. I wonder how long it’ll be before he’s so gone that he’s not my dad anymore. If there’s a line, he’s standing on it.

Once he’s asleep I go into the living room. I pull the top notebook from the pile under the coffee table.

I need five babies. They’ll have to be the tiniest newborns – anywhere from brand new to two months – so I can train them and use them before their fingerprints form. Most people don’t know that babies don’t have fingerprints at birth. The nurses take an ink stamp of the foot print after the baby pops out, which can identify it to some degree. And they have a hospital band that gets fastened around the baby’s wrist, which sets off an alarm, locks all the doors, and kills the elevators if the baby’s taken out of the ward. They have lots of security in place for these little people, but when a baby touches something with its fingers, it’s like nobody was ever there.

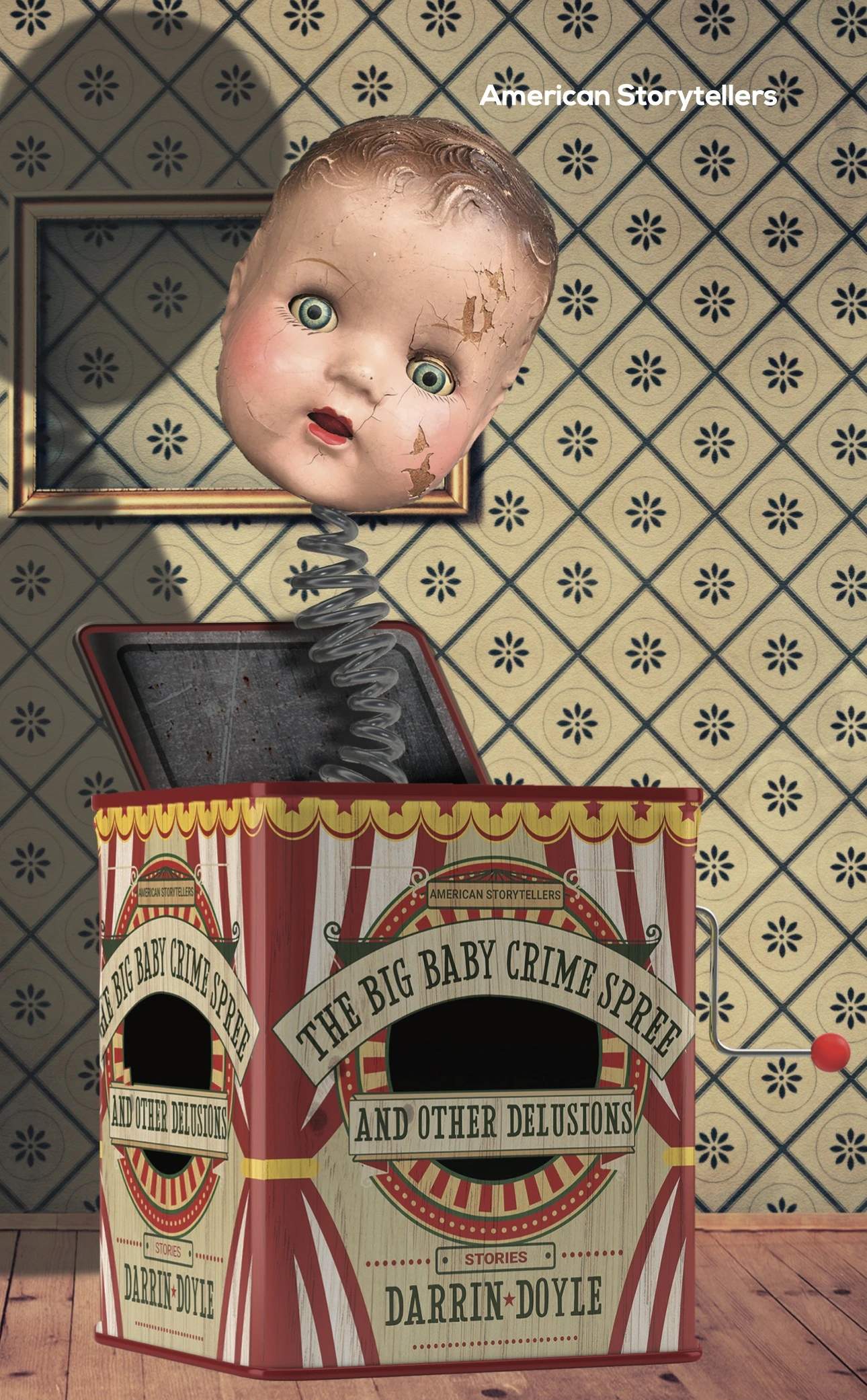

Darrin Doyle teaches at Central Michigan University. The Big Baby Crime Spree and Other Delusions is his fifth book of fiction. He’s the author of the story collections Scoundrels Among Us and The Dark Will End the Dark (Tortoise Books) and the novels The Girl Who Ate Kalamazoo (St. Martin’s Press) and Revenge of the Teacher’s Pet:A Love Story (LSU Press). He lives in Mount Pleasant, Michigan with three other humans and a cat. His website is darrindoyle.com.