By Eileen Favorite

Sandi Wisenberg (who publishes as S.L. Wisenberg) is a Chicago literary icon; she was named a New City Lit 50 Nonfiction Hall of Famer in 2023, she’s the editor since 2017 of the local and international literary journal, Another Chicago Magazine. I can’t remember not knowing Sandi Wisenberg, nor can I remember how we met. In mid-90s Chicago, before there were MFA programs housed in local institutions, I relied on community workshops to get feedback on my work. Sandi led some workshop somewhere that I enrolled in, and I was drawn to her warmth, the wry twinkle in her eye, and her dogged focus.

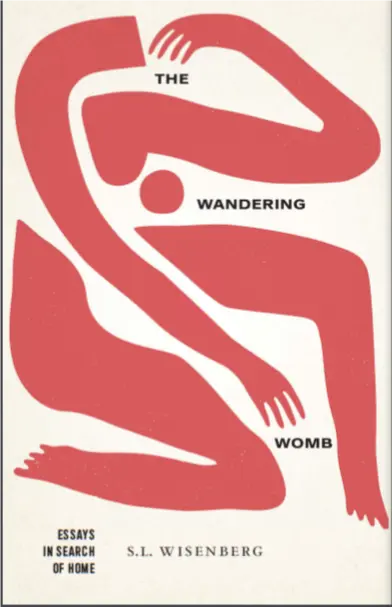

A journalist, fiction writer, and essayist, Sandi is a writer’s writer. In many of the twenty-eight essays in her new collection, The Wandering Womb (WINNER OF THE JUNIPER PRIZE),she interrogates place as a determinant of identity, and whether that home is embraced, rejected, or tragically escaped. Her curiosity is informed by a mind eager to mine contradictions. She questions “vampire tourism” on a visit to Auschwitz, explores her sexuality with lesbians in Fort Lauderdale. Her takedown of 1970s fashion advice to budding Texas girls will curl the toes of anyone born after Y2K and shiver the timbers of women of her own generation. Whether digging through archives to learn more about a rabbinical ancestor, or interrogating the tragic and inspiring life of Rosa Luxemburg, Sandi explores her subjects with brainy and empathic rigor.

I was lucky to have a chance to ask Sandi some questions about how feminism, diaspora, and Jewish identity infuse her work.

EILEEN: In the titular essay, “The Wandering Womb” can you explain what the idea meant to Plato, and how you see the metaphor now? Why did you choose it as the title for the book?

SANDI: Plato, like many other male “experts,” saw the womb as an alien object inside the alien sex. He called it a wild animal. But it must be noted that he also saw the penis as a separate living thing. For many eras, the womb was believed to actually wander inside a woman’s body. As I write, “Hippocratic physicians wrote that women who were ill might be plagued by a wanderlustful womb….” If it traveled to the head, it could cause a headache, if it sat on a chest, it could cause near-suffocation. This sounds so ridiculous, but we still live in a world where women’s physical complaints and pains are not taken seriously enough. Even though a good friend (male) told me that men would never buy a book by this title, I decided to use it. The notion of women as people with alien bodies is the foundation of misogyny that is still with us. I also see myself as a wandering womb, using the womb as synecdoche. A lot of the book is about my travels—first from my hometown, Houston to the Chicago area, then Iowa and Florida, and then to Turkey, Poland, and France. I wander. Looking for—happiness, or relief from melancholy. I found that relief at home, in a way—from a prescription for Prozac. And, to go back to the womb, the Greek word for it brought us the word “hysteric,” which was mostly the province of women patients, especially those of Freud and his associates. I wrote about one of those patients in the title essay.

Two people, who are not Jewish, saw the title as suggestive of the term “Wandering Jew.” I didn’t think of that, and had to look up the origin of the term. It’s from an antisemitic story about a Jew who made fun of Jesus when he was on his way to crucifixion, and who was punished by having to wander the world. On the other hand, for many Jews, the term brings to mind the condition of the Jew: always persecuted and therefore having to wander the world. But again, I did not have the word “Jew” in mind when I chose the title, at least not consciously.

EILEEN: In “Auschwitz: Like the Back of His Hand” the self-proclaimed expert Alan says, “I know Auschwitz like the back of my hand.” I love your ear for the comic in this tragic expertise. You also analyze “vampire tourism” versus bearing witness. Can you talk about how one walks the fine line between these two approaches to traumatic history?

SANDI: You just have to keep thinking about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. If you want to read more about this, I recommend Jerry Stahl’s Nein, Nein, Nein!: One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust. I was able to interview him about it, and it will be in the American Book Review. In Nein, Nein, Nein!, he writes about a tour of the camps. It’s really funny but also thoughtful. For better or worse, I’m always watching myself. It may be the condition of the writer. I’m watching others, too. I so often notice the absurd and the surreal. There’s a reaction you’re supposed to have to Auschwitz, and people don’t always have that reaction. I like to mine the gaps.

EILEEN: Walking that tragicomic line is no small feat. You do something similar in “The Year of the Knee Sock.” The ways girls were educated and socialized to dress and talk so they appeal to boys is both infuriating and absurd. But then, you bring it all down to a beautiful piece of advice: “If you don’t know how to say yes to pleasure, you’re not going to know how to say no.”

SANDI: We were being taught that basically boys wanted what we weren’t supposed to give. (There was also the saying, Why buy the cow if you can get the milk for free?) Now look at that language! No one ever talked to me about pleasure, except a friend in high school who really liked making out and maybe more with her boyfriend. And I think there was an ounce of guilt as she spoke. More typical was another friend who was afraid of sex in junior high. A guy came to visit her while she was babysitting, and they made out. She was afraid he would call her a bitch because of it. I was sixteen before I ever French-kissed anyone and when we lay down together outside, I was thinking only what I wouldn’t allow him to do. I didn’t enjoy it that much because I wasn’t attracted to him. But I wouldn’t have been able to say that then. I was very much attracted to the next boy who came along. We were like babies in those days. Then in college I read The Hite Report. That was helpful. Before I read that, I thought I masturbated incorrectly.

EILEEN: How is that even possible? In “Spy in the House of Girls”you contrast sorority houses at Northwestern and your residency at the Millay House. How did the residency open you to the insight of the final line, “I will bury the Queen of the Prom”?

SANDI: I have no idea. In grad school and in Miami, a few years before the residency, I did a few Wiccan and feminist rituals (such as burying cuteness, which I mention in the book) so I was thinking that way. We had a Barbie board game when I was young. I think it was The Barbie Game: queen of the prom (TM). I just looked that up online. So I guess I should have had the trademark sign in the essay. Whatever Barbie game it was, the purpose was to go to the prom with Ken, or maybe Ted or Tom, but not Poindexter. We also had a game called Park and Shop. I guess that after being Barbie, you became a suburban matron. You competed to get all your shopping done. It wasn’t as fun as the Barbie game, though. Poindexter, by the way, was nerdy with glasses. He probably became an IT mogul.

EILEEN: As much as I see that socialization as fairly typical, there does seem to be something particularly Southern about it as well. In “Grandmother Russia/Selma,” you write about the Southern Jewish experience. Do you feel that Southern Jews are underrepresented or misrepresented?

SANDI: Jews in the South knew about Northern/Eastern Jews, but we didn’t know that they didn’t know about us. Jews from more Jewish parts of the country think we’re an anomaly. We thought we were normal. My father’s side of the family came to Selma from Lithuania. Selma had a Jewish community (there are three Jews left) and had three Jewish mayors. The Jews were peddlers, storekeepers, and later owners of department stores.

In the late 19-teens, my father’s family moved from Selma to Laurel, Mississippi, which was a lumber town incorporated in 1882. When I read old newspapers from the time, the Wisenbergs were in Laurel, I saw them and other Jews listed in the Society column (unlike Blacks). The Klan was active in the South, and did attack Jews in the 1920s, but my fathernever mentioned the Klan. He would tell the story of a friend of his father’s asking his father to join the Baptist Men’s Club in Laurel. His father said, “But I’m Jewish.” His friend said, “Oh Sol, we don’t consider you a Jew.”

EILEEN: As if that were a compliment.

SANDI: Exactly. When I was in Selma I heard that in the 1960s, the Klan didn’t like the brochures they got from the national KKK because they were anti-Semitic. Only one person told me that. But it was true that Sheriff Clark’s right-hand man was Jewish.

The family moved from Laurel to Houston in 1932. The Houston Klan had been active against Jews in the 1920s, but again, the family didn’t mention anything. My father said he heard one anti-Semitic slur in his life–when he and his sister were walking down the street, either in Houston or Laurel. But the slur the person used was for Italians.

EILEEN: That’s an absurd, but strangely familiar act of bigotry in America, isn’t it? At the end of the essay, the afternote says, “The whole meaning of Russia has changed since I wrote this.” How has your view of Russia shifted since you wrote the essay and since the invasion of Ukraine?

SANDI: I think that Russia now has become the same as the Cold War Soviet Union: a repressive place where there’s a military draft and no freedom of speech.

EILEEN: How do you make distinctions among Russians, Russian Jews, and Russian-American Jews?

SANDI: I don’t know any non-Jewish Russians. I know some former Soviet Jews in the US. In the Soviet era, Jews were discriminated against and once they declared they wanted to emigrate, they lost their jobs. Stalin gave the Jews a Yiddish territory, but he also killed many Jews, among millions of non-Jews. I do know one Russian Jew whose parents, he says, are big supporters of Putin. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, my family lived in the czar’s land, but they didn’t consider themselves Russian or Lithuanian or Belarusian. They were Jewish.

EILEEN: That’s their primary identity. As Americans, I think many people do give primary emphasis to one identity, even when we’re a hodgepodge of secondary and tertiary identities. In “French Yoga” a French-speaking Moroccan-American in Chicago teaches yoga to native English speakers in French. The many levels of culture and language you describe in this yoga class make the experience rich but also mind-blowing. The final line is, “…we walk out the door, into America.”

SANDI: Yes, my grandson’s name is Aiden, and I thought the name was strange at first,since he’sbiracial (American Black and Panamanian on his mother’s side, and on my stepson’s side, Ashkenazi Jewish and German-American). But why not? Aiden means “little fire” and his father has red hair. The name comes from the Gaelic. I’m used to babies having family names–Ashkenazi Jews name their babies in memory of relatives who have died. (It’s common to ask, Who’s she named for?) But why can’t Aiden have that name? We read James Joyce, we eat papusas, I speak French, I like reggae. My mind is like my writing—it’s a mosaic in there.

EILEEN: A lovely mosaic, indeed! Do you see yourself living a life of both the body and the mind?

SANDI: I’m very much in my mind and maybe that came about because I wasn’t carefree in my body because of asthma. But I’ve done yoga and breathing for decades, and maybe that helps. I also used to get a lump in my throat from persistent anxiety. Nothing helps that but meds.

EILEEN: In “Mikvah” you include “Parable: The Seven Wise Men and the Menstruating Women.” Who wrote that masterpiece?

SANDI: Me. Thanks.

EILEEN: Reader, you must read it!

Eileen Favorite’s novel, The Heroines (Scribner), has been translated into five languages. Her essays, poems, and stories have appeared in Chicago Magazine, The Toast, Triquarterly, The Chicago Tribune, The Rumpus, Diagram, and most recently, The Manifest-Station, and others. Her essay, “On Aerial Views,” was a Notable Essay in the Best American Essays 2020. She was named a 2021 Illinois Arts Council Awardee for nonfiction. She teaches writing and literature classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. eileenfavorite.com

S.L. Wisenberg is the author of The Wandering Womb: Essays in Search of Home, winner of the Juniper Prize in creative nonfiction, and shortlisted for the CHIRBy (Chicago Review of Books) award in nonfiction. She’s also the author of a short-story collection, The Sweetheart Is In; an essay collection, Holocaust Girls: History, Memory, & Other Obsessions; and a nonfiction chronicle, The Adventures of Cancer Bitch, which will be out in paperback in October 2024. She’s received a Pushcart Prize, and fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, National Endowment for the Humanities, Illinois Arts Council and Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events. She’s editor-in-chief of Another Chicago Magazine.