By Susan Baller-Shepard

In the back of a van speeding up Monte Erice, the Mountain of God, not far from Trapani in Sicily, I met Jody Hobbs Hesler, a writer who would become a dear friend. Battling jetlag and anxious about the conference ahead, I felt calmed by her presence. It’s the same way I feel reading her prose, knowing I’m in the hands of a skilled writer and tactician.

After attending Breadloaf Sicily, Jody and I formed a writing group with other writers at the conference and called it “the ArmadillHers.” The ArmadillHers set a goal to meet up once a year and write together. We embraced the armadillo mascot, an animal possessing a tough skin, soft underbelly, and wisdom to know when to circle in on itself—all attributes helpful for writers.

Jody lives and writes in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and, not unlike Flannery O’Connor and other Southern writers I admire, Jody examines the turning points in her characters’ lives with unwavering attention.

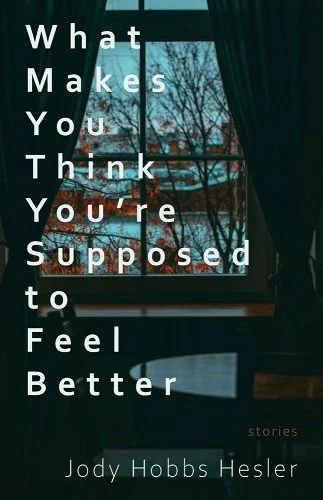

Jody’s short story collection, What Makes You Think You’re Supposed to Feel Better, launches October 15th, published by University of Wisconsin Steven’s Point Cornerstone Press. Her novel Without You Here, is forthcoming from Flexible Press in November 2024. While her stories and essays have found literary homes all over the web and in literary magazines, I especially appreciated her brilliant essay on rejection in Atticus Review titled “A Red-Headed Stepchild Reflects on Rejection.”

In Sicily, while touring the town of Erice, our tour guide told us, “The divine feminine never died out here. The mountain once held a temple to Venus, which was also a lighthouse, and you’ll see the churches all have the Madonna front and center.” Some things have staying power. You’ll find this with Jody’s writing—it will stay with you long after you’ve read the last page.

You are a writing craftswoman, and I want to ask you about craft. I was fortunate to hear your craft talk, Narrative Tension: The Promises Writers Make at the 50th anniversary of the North American Review Conference. In that craft talk, you compared narrative tension to properly placed dominoes: If you have all the story elements in place correctly, they will fall one after another with the momentum you’ve created. You handle narrative tension with aplomb in What Makes You Think You’re Supposed to Feel Better. How do you personally judge when an element is not falling into place?

First of all, thank you! That’s absolutely lovely to say. And now I’d like to answer the metaphor in this question with another. When I’m thinking of a story “lining up” correctly, besides dominoes, I also think of chemical equations. I was not an enthusiastic student of chemistry in high school, but something about those equations stuck with me. You fiddle with a whole bunch of elements on one side and a bunch of different ones on the other, and, when you’ve worked the problem correctly, chemistry says that’s balanced. Literary balance feels similar. Balanced, but the two sides look nothing like each other. There’s a temptation to match every action in a story with a resolution, but it’s usually more effective to leave some questions unanswered. Choosing which require answers, which details outweigh the others, which actions demand equally and opposite reactions (to switch up the metaphor to physics), that’s where the hard work is. If we focus on the wrong details, the tension in the story will dissipate or fluctuate out of our control. When we strike the proper balance, the tension in the story stays sharp. And I never know when I’ve done it until it’s done.

Your characters are wonderfully diverse. In “Alone,” “Sweetness,” “Sorry Enough,” “Everything Was the Color Red,” and “Heart Blown Through,” in particular, your characters take risks which could cost them a great deal. How do you determine the risk(s) each character is going to take? How do you gauge when a risk is too much or too little for a story?

This question reminds me of an incident that happened years ago when I was driving through town with my youngest. A man loped into the middle of the street, right in front of us. He was moving slowly, sort of cluelessly, but that struck us as more frightening than if he had charged directly at us or into traffic, waving his hands and screaming. With behavior so close to normal, it’s extra hard to predict what might happen next. For me, people’s behavior is scariest, and maybe riskiest, when it falls just outside the limits of our expectations. I like to keep the risks in my stories in this weird zone. For one thing, it makes the writing interesting—now I have to play out whatever unpredictable thing must happen next. Also, when the risks are a baby-step out of step, characters are less likely to cross into utterly far-fetched territory. In early drafts, my characters tend to go in one of two directions. One, they might behave appropriately, which is just boring, or they might take a wild running leap across those expectation boundaries and way beyond what readers would buy. When the former happens, I have to push my character to behave more spicily. When the latter happens, some inner voice tsks and says, “Nah,” and I know I have to look again.

About your writing process, some of your stories deal with parental longing, parents in some way longing for something from their children, parents trying to reestablish a connection with adult children, or people longing for something they’ve lost. You are skillful at telling this through objects like sidewalk chalk, an afghan, or a giant M&M figure.

How do you pick objects to convey a part of the story? The writer Roxane Gay talks about writing in her head before committing her work to the page. Do these objects come to you before you write, or as you write?

Most of the time, I picture these objects sifting down from a magical story ether swirling above our heads. Detritus drizzles down alongside them, too, so it’s a matter of panning through what lands in a story and paying attention to what glows or detonates and what doesn’t. At a writing conference a long time ago, Jill McCorkle said, “Never underestimate your subconscious,” a line I quote often, and advice I do my best to heed. Our earliest drafts might be globs of disaster, but somewhere in them are these pearls to find and polish.

Sometimes, though, life presents an object before I have a story to plug it into. That’s the case for the big red M & M. On my husband’s way home from work one day, he witnessed a local businessman wrestling such a creature into his car. We both cracked up as he tried to describe what he saw, and I was left with so many questions. Eventually, those questions found a story to answer them, and the M & M found its home.

Another craft question. Some of your stories are told in third person close, and some in first person, how do you determine which point of view to use for a particular story?

Every story asks for something different, and sometimes I bounce from one point of view to another until it’s clear who the story belongs to and what distance we need from that character to absorb it most effectively. Early drafts of “Heart Blown Through” were in first person, but when I got to scenes where Irv was tempted at the bar, I felt that point of view pushed the reader away. His wife is in ICU. How much patience can we spare for a guy telling us directly that he’s sort of attracted to a stranger at a bar? Close third often introduces just enough space between us and the character to show their behavior without implicating us in it, and/or to show us the behavior along with a third-party pathos that softens our judgement. Implicating the reader and judging the character are the whole point for plenty of stories, but not for this one.

In “Things Are Already Better Someplace Else,” I resort to second person. This vantage can act as apostrophe to an unseen other character, or it can address the reader directly, or, as in this story, it can act as a kind of refraction from a direct first person. In the devastating first moments of a child’s abduction, which is the situation in this story, I imagine a mother’s thoughts turn molten and wordless, which would pose a huge challenge for first person narration. The effect of second person becomes almost dissociative, as if the person is considering herself as someone else, “you” instead of “me,” which seemed the best fit for this story.

Congratulations on your debut novel Without You Here (Flexible Press, November of 2024). Since you clearly know the pacing of the short story form, how do you manage pacing in a long form like a novel?

Your questions are so good because they hit on the very things that occupy the most time and effort in revision. How indeed do you manage pacing in a novel? I don’t know how many entire versions of Without You Here I wrote before landing on the final one. This story posed its own special set of challenges. In it, eight-year-old Noreen loses her kindred spirit aunt to suicide. The two shared physical as well as more ethereal qualities, and the family weighs Noreen down with their worry that she’ll repeat the pattern, which has other echoes in their family tree. The novel includes about as many chapters from the aunt’s point-of-view before her death as they do from the niece’s point of view afterward. My first draft was entirely linear, which didn’t work because the death sparks the story’s pressure, even though it happens twenty years before the book ends.

There are a million ways to solve this problem, and I probably tried half of them, but it was important to me to demonstrate how trauma reverberates across time. Picture throwing a pebble into a puddle. Concentric circles radiate from the splash, all the way to the outer rim of the puddle, where their effect is largest. Trauma can work like this, not so much like the typical Freitag triangle of inciting incident, rising tension, crisis, and resolution. Jane Alison’s craft book Meander, Spiral, Explore offers a host of other shapes a plot can take, and reading it inspired me to keep searching until I found the best shape to fit this book. Spoiler: It’s a spiral shape, so the action returns again and again to the past, keeping the tension fresh.

There are many poignant moments in What Makes You Think You’re Supposed to Feel Better. For example, this line in “Sweetness” took my attention: “Everything here was better than us.” “Sorry Enough” made me cry and a character in “Harmonie” made me cringe in all the best ways. You never tip into sentimentality or melodrama. What is your writing litmus test for pathos in a story?

Here I get to quote another brilliant writer. In a conference workshop, Tim O’Brien once said, “Don’t be afraid of sentiment. Be afraid of fraudulence.” In other words, go for the emotion, but don’t force it, don’t exaggerate, don’t lie.

Tuning a story’s emotions falls under the chemical equation metaphor. Too much focus on a character’s crying, say, telegraphs to the reader what we, the writer, want them to notice, unbalancing their experience of the story. I like when a separate character comments on the primary character’s emotions instead. “What, are you crying again?” Then the emotion reflects the characters’ specific relationship and contributes to the tension in the scene. There are other strategies, too, that de-center the experience of the emotion and re-center the tension in the story, skirting sentimentality. Maybe the trick is to make sure we’re not just in the upset character’s body, but we’re in the whole room, the whole story of their experience. The scope has to be wider than the moment.

There are lines in your stories which stop me short with their beauty. Take this line: “Your Beverly is a smudge of a child.” I read and reread them. Usually these beautiful lines are succinct, giving the reader more information and adding emphasis to the story. What are your instincts about when a lovely line will stop the forward progress of a story and when it will enhance the plot of the story?

A line can’t just be pretty. It has to matter. It has to match the rhythm and diction of the story. If it calls too much attention to itself, it stops doing the job of bringing the story to the reader. If I didn’t love how words felt and sounded, I definitely wouldn’t be a writer! So it can be excruciating to weed out beloved but needless lines. Several revisions in, if I find myself double-taking at a certain line or moment in a scene, I know something’s off. I might rewrite that moment a hundred times trying to salvage a line, only to discover that the cure for the scene is deleting it.

As someone who has lived her life in Virginia, you are in the very good company of other Southern writers including Eudora Welty, Zora Neale Hurston, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Conner, William Faulkner, Reynolds Price, among others. Is there a southern writer whose work resonates with you? How do you see your work fitting in with this cadre of writers, or do you?

I love Southern writing. Add William Gay, Lee Smith, Larry Brown, Kaye Gibbons, Harriette Simpson Arnow to your list. I love the dirt-under-the-fingernail awareness of place, the colorful expressions, the complicated people, the lens on good and evil. I love regional writing from all over the world for the same reasons. I’ll stop short of placing myself among these Southern literary rock stars, but they’re definitely influences. The songwriter Aimee Mann is another influence. She’s about my age and we grew up on opposite sides of the same county. Her music captures the Mid-Atlantic suburban vibe, which is my region’s spin on Southern. The county where we grew up transformed from rural to suburban while Richmond grew from a sleepy Southern city to the murder capital of the world, a side effect of the crack epidemic. The brand of summer boredom we suffered during those years feels trademark specific, and it saturated my creative/literary sensibility.

You’ve long been involved in the writing community. You teach at WriterHouse in Charlottesville, Virginia, you write reviews for The Los Angeles Review, youprovide editorial support for various publications, you attend writing residencies and conferences and serve as a presenter, moderator, or panelist at conferences and writing events. What energizes or inspires you about the writing process in light of these collaborations?

Connecting with other writers and artists gives me oxygen. Sharing what I’ve learned as a teacher reminds me, re-teaches me what I’ve learned, and it introduces me to what my students already know and to their fresh takes on literature and the world. Presenting at conferences is another avenue for resource sharing. Whenever I share, I open myself up to be shared with, so invariably I benefit. Reviewing books and reading for The Los Angeles Review give me opportunities to celebrate other people’s work while discovering new writers and interesting stories and books. I consider this literary citizenship, so it’s giving back to my community, but it’s also keeping me sharp and engaged with what’s happening in the literary world. There’s also just the pure human element. We need people. They keep us loved and generous. We’re in cynical times. We can use all the love and generosity we can find.

With your exposure to all these writers in the wider writing world, whose work or books would you recommend we read now? Is there a literary journal you always pick up or look up online to read?

From my recently reviewed pile I highly recommend Shena McAuliffe’s We Are a Teeming Wilderness, Rebecca Bernard’s Our Sister Who Will Not Die, Louise Marburg’s You Have Reached Your Destination, Lisa Cupolo’s Have Mercy On Us, and Carol Roh Spaulding’s Mr. Kim and Other Stories, all of which are kickass story collections that run the gamut from experimental to dryly witty to emotionally and historically expansive. Also, a general shout out to everything Ross Gay does, especially for bringing joy and delight to the forefront of public discourse. As for literary magazines, I always enjoy CRAFT, The Common, Oxford American, Valparaiso Fiction Review, to name a few. And a literary journal hack I highly recommend is Journal of the Month, which sends you a different literary journal every month to give you a break from deciding which to subscribe to.

Jody Hobbs Hesler has written ever since she could hold a pencil and now lives and writes in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Growing up, she split time between suburban Richmond, Virginia, and the mountains outside Winchester, Virginia. Experiences of all these regions flavor her writing. Her debut story collection, What Makes You Think You’re Supposed to Feel Better is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press in October 2023, and her debut novel, Without You Here is forthcoming from Flexible Press in November 2024. She teaches at WriterHouse in Charlottesville, Virginia and reads for The Los Angeles Review. Her writing has appeared in The Westchester Review, Chariot Press, The Los Angeles Review, The Bangalore Review, The Petigru Review, Arts & Letters, Valparaiso Fiction Review, Prime Number Magazine, The Raleigh Review, along with other publications.

Susan Baller-Shepard writes along a wilderness track, amidst cornfields and big skies. Her essays, poetry, photography, and sermons have appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post’s “On Faith section,” Spirituality & Health, Writer’s Digest, Intima: A Journal of Narrative Medicine, Typishly, Patheos, Day One, the Tattooed Buddha, and other publications. Her poetry has been featured on WGLT-FM Poetry Radio. Her poetry collection Doe, from Finishing Line Press, included a poem featured on The Writer’s Almanac. She has two poems in an upcoming anthology from MadHat Press about Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. Baller-Shepard completed a novel with Writing by Writers DRAFT program based on the life of Hattie Hays, a woman living in Illinois along the Mississippi during the Civil War, while her husband fought for the Union Army. Currently she’s working on a new poetry collection. She’s been an activist and ordained Presbyterian minister for thirty-two years.