Interviewed by Christine Maul Rice

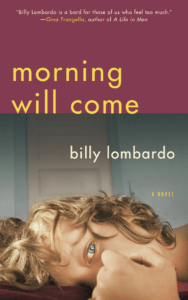

Billy Lombardo’s masterfully realized Morning Will Come (Tortoise Books) explores what remains in the murky wake of tragedy. After their daughter’s disappearance, Audrey and Alan Taylor struggle against grief to navigate the sharp edges of a forever-changed marriage, tripping along a path toward a relationship recognizable but forever altered.

Morning Will Come captures fleeting moments of what it means to be held close by a family—in all its beauty and imperfection—and I found Lombardo’s opening chapter one of the most remarkable I’ve ever read. Lombardo presents Alan and Audrey Taylors’s grief with the delicacy of a surgeon, laying bare their struggle until it hurts to look.

Originally published in 2009 as How to Hold a Woman (Other Voices Books), Morning Will Come examines the nuance of human connection with remarkable poignancy. Lombardo’s razor-sharp prose will capsize you.

After reading Chapter 1, I thought: This is one of the most perfect first chapters I’ve ever read.

Christine Maul Rice: Hi, Billy. How’s it going?

Billy Lombardo: That’s a beautiful way to open an interview, Chris. Thank you. As for how it’s going, it’s going strangely. I hope it’s the strangest period we’ll ever go through. But there have been some lovely moments in all of this.

CMR: I hope so too.

Besides talking about the re-release of your novel, I want to ask you, first, about two other things: cooking & baseball.

At your Volumes Bookcafe launch, you made pizza and I understand that you’re a baker. What have you been creating lately? What has been comforting during this time?

BL: A part of me feels that any kitchen, and all the things in it, knows if you’ve spent some time in it. I started making bread pretty much every Sunday when my son, Kane, was walking. I wanted him to remember the smell of home baked bread. I got pretty good at it, and the kitchen started cutting me some slack. I’d bake salmon for the first time, and it would be among the best salmon dishes ever. A New York strip steak, the best I’d ever eaten. Cheese cake, white fish I’d caught on a fishing trip. Mediterranean chicken. This is a weird time for shopping, of course, and cooking. We’ve been having rice dishes and soups. Pasta e Fagioli is a go-to favorite, fish dishes, pizza—it’s gotten so I can’t eat pizza I haven’t made myself. Potato focaccia. I make a cauliflower and potato soup pretty regular. It’s therapeutic.

CMR: As a leftie myself, I’m especially fond of your first novel, The Man With Two Arms.

I realize there are so many other things to worry about but by way of diversion…

Are you a big opening day person? How are you faring without spring baseball?

BL: There’s never been a shortage of things to worry about, so it’s nice to think about baseball. I went to a home opener once, on the strength of a student’s skybox tickets. I do love opening day. I love when pitchers and catchers report. And we still had that this year. When I give in to the worries of the world and stop following baseball closely, my son pulls me back with news from the White Sox organization. He played college baseball, and so, my thoughts around this time are no so much about the fans missing their games and their spring seasons. My thoughts lean toward the players—from tee ball to the majors, for boys and girls everywhere. There’s nothing quite like the blue of a game delayed. I can’t wait to see them take the fields again.

CMR: A lot of people are asking me if I’ve been writing. I have to admit that it’s been a bit of a struggle. How about you?

BL: I was on a nice little roll there with the revision of a novel I’ve had around for years. I’m copy editing it slowly now. I’ve never gotten too anxious about days and sometimes months going by without writing. It comes in spurts for me. Sometimes I’m trying to figure out how to make ends meet, how to grow my little writing and editing business, and my efforts shift in those directions, which means I’m writing and editing and wordsmithing and teaching and reading and thinking—and all of those things are tools I’ll be able to put to use when the next writing spurt comes along.

CMR: Tell us about your writing and editorial business. How has it grown out of your experience as a teacher and writer?

BL: What a strange journey it’s been. It was an accident that I got into teaching at all. Dumb luck, really, and a long story I won’t go into now. I taught religion and speech and morality and ran a service program at various schools for 20 years before I backdoored my way into the English department at the Latin School. When my first book won a contest and was published, it opened up the world for me in a way that blew my mind. I had grown up in a house with no books, let my stupid behavior speak for me for years, and now I had finally put words to my own life. The publication of that book, The Logic of a Rose, coincided with the first issue of Polyphony Lit, the student-run, international lit mag I founded. I realized that the magazine was doing for high school writers what it had taken me 40-some years to do for myself, (i.e. language my life). Mid-career, that realization shaped my teaching, and it was then that the work of writing, teaching and coaching writing, editing, and developing young editors became my life’s work.

So, I started putting myself out there as a writer and editor for hire and finding more time for my own writing. Since then, I’ve done some work on government contracts, written articles for people in the business sector, coached kids from Chicago to Shanghai through college essays, edited proposals for cannabis businesses, edited a case study for a product designed to detect and analyze arbitrage in crypto currency coin offerings, and edited novels and memoirs. All of it has been weirdly interesting and fascinating.

CMR: I don’t know if you remember this but years ago I invited you talk to my Columbia College Chicago grad students about publishing a lit journal. It was during a cold snap because you walked off the elevator and you weren’t wearing a hat or gloves and it was freezing and I was worried about you because you were so cold.

Once you warmed up, it was a really lively discussion and class visit.

BL: I remember the visit, but not the cold. I don’t doubt the lack of hat or gloves, though. It’s taken me a long time to figure out the value of good, warm clothing.

CMR: Anyway…you discussed what you’d learned from starting a literary magazine. For those who don’t know about Polphony Lit, it is a “global online literary platform for high school writers and editors.”

How did Polyphony Lit come to be?

BL: One of my students came to me in 2003. She wanted to start a fiction magazine at the school. We already had a literary magazine, though, and I knew getting fiction would be tougher than getting poetry, so I suggested we seek poetry and essays, too, and also go national. The inaugural issue came out the same month my first book, The Logic of a Rose: Chicago Stories, came out. That little book changed my life, and the convergence of its publication with the first issue of Polyphony Lit, was a bit miraculous. We got a little startup money from the head of school at the time, a visionless man whose name was almost a swear. When he gave me the paltry $3000 a year for three years, he said, “I know the way these things go. When the money runs out, the magazine dies.” Well, the magazine has grown into a global online literary platform, and that money, which actually came from a parent and not the school, anyway, stopped coming in 2007. Now, Polyphony Lit is a nonprofit.

CMR: In her forward to Morning Will Come, Gina Frangello wrote about how she urged you to shape what was a collection of stories into this novel. She made an impassioned plea for it, in fact. As the story goes, a few weeks later you emailed her to say you’d finished the novel.

This is going back…but at what stage did you believe that the collection could be shaped into a novel?

BL: I was pursuing a low-res MFA at Warren Wilson College at the time, with maybe four or five disconnected stories from HTHAW written. Gina was at Other Voices at the time, and was looking to publish a collection of short fiction or a novel in stories, and so I wanted to put a few more stories together, but I didn’t mind if they weren’t connected. It was my first residency at WW, and my workshop class had read The White Rose of Chicago. I think a couple of students in the workshop didn’t quite know what to make of the story, but the teacher, Wilton Barnhardt, stood up and gestured fluently, and said, “But what if Audrey is grieving over the death of a child?” I had written that draft without knowing what Audrey was grieving over, or even that she was grieving. That helped me tie a couple of the stories together, but it was Gina who really helped me to see what the book could be.

CMR: This was your first novel, yes? How feverishly did you work on it after Gina spoke to you?

BL: It wasn’t the first time an editor had shown interest in my work. The first was Debby Vetter, an editor at Carus Publishing, the magazine group that includes Spider and Caterpillar and Cicada. Debby edited one of the stories in The Logic of a Rose. She knocked off 400 words (at a quarter a word), found internal rhymes, informed me of all of my rookie tics, and taught me more about writing than anything I’d known before that edit. It thrilled me. I still have her edit around here somewhere.

To answer your question, The Logic of a Rose came first, but I simply had nothing in my toolbox but an interest in language, a boyhood, and this fragile heart. Though I love that little book, I hardly knew what I was doing. I was most excited about getting it out in the world and having someone review it in a smart and critical way, so that I would learn something about what I was doing. Gina served that purpose for me with Morning Will Come. She let me know, while it was in progress, that it was a thing of value, and that I was doing something right. She also let me know that there were ways I could bring the manuscript to a better place. She was there for me at a critical time, because she let me know that the first book wasn’t a mistake, that I was doing something with Morning Will Come that was worth putting out in the world.

And once we had that meeting that Gina speaks about in the foreword to MWC, I went at it night and day until I was done. I got it back to Gina so fast, she thought it was bound to be terrible.

CMR: What was behind the title change from How To Hold A Woman to Morning Will Come?

BL: I absolutely loved the original title, but after all these years, it felt like a misrepresentation of the book. It was missing the hope that was always essentially a part of the story for me. And when it was clear that the book had a shot at being re-introduced to the world and to a new generation, Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein and hordes of other terrible humans that assigned unwanted permutations to the former title.

CMR: You seem to write (as I do) on the verge of discovery. Do you? Or do you outline, know where the story is headed?

BL: Absolutely. The first time I heard a professor use the term discovery draft instead of first draft, I knew I’d never use the term first draft again. I’m not an outliner, though I’ve learned to go back and retrofit an outline after I’ve completed a draft or two. I don’t often hit the perfect structure organically. It’s work. And the longer form stuff, I’m still trying to figure out. That requires greater attention to structure.

CMR: I read that, while writing The Man With Two Arms, Henry Granville’s character took you by surprise. What character most surprised you in Morning Will Come?

BL: I’m not sure any of them surprised me. What caught me by surprise was what happened to me. That book mostly started with five stories that were told to me. What surprised me in the end, was my realization that I was trying to language my own grief by trying to understand Audrey’s.

CMR:That’s a beautiful way to think about creating art.

In the first chapter of Morning Will Come, there’s a heartbreaking scene where you managed to capture the fragility and beauty of a young family before tragedy strikes. The juxtaposition between that chapter and the next—showing a family on the edge and then tipping over the edge—was so wonderfully realized.

As I mentioned, Chapter One is so lovely. It still appears in my mind so clearly. Those moments of love and clarity are the most nuanced and difficult to capture because they are so ephemeral, so difficult to write.

Can you talk about that first chapter?

BL: Many of the plot markers are unchanged from the story a colleague—an animal behaviorist—told me. I remember laying down, like tracks in recording music, my own sadness. I remember weeping while writing it. Which is not rare for me—neither weeping nor weeping while writing.

I guess, thinking about it now, that Isabel surprised me. Her burgeoning adolescence, her obsession with Gatsby and Daisy. She’s the closest I’ve come to having a daughter, really.

CMR: Reading the intro by Gina Frangello, I thought about what a great writing group that must have been: Gina, Elizabeth Crane, Megan Stielstra.

Are you still involved in a writing group and, if so, what do you get from sharing your work with trusted readers/writers?

BL: Patrick Sommerville was in that group as well. I’m not in any writing group now, but two of my closest friends and I get together (when people got together) to go on two/three-day writing trips. And we’ll take a look at what one of us has been working on, and talk about it. It’s very much like a writing group, but without what feels to me like the pressure to produce really effective commentary on another’s writing. It’s hard work.

CMR: What has the experience of re-releasing Morning Will Come been like? How has it differed from the original release?

BL: Aside from the cover, the title, and the light edit Jerry Brennan (Tortoise Books) put it through, nothing has changed. The best feeling is that a book I was attached to, a book I’m proud of, has had another life. It also urged me to work on a website or two and to learn a bit more about how to get a thing out into the world. Also, I love doing readings and Q & A sessions. Remember readings?

___

Order Morning Will Come.