By Christine Rice

Christine Sneed has put in her 10,000 hours and then some, Mr. Gladwell. I first heard Christine read last winter on a frigid, snowy night at a Come Home Chicago event at the Underground Wonder Bar. Tell you the truth, I went to hear one of my favorite writers, Stuart Dybek, but walked out of there with a new favorite.

Her first collection of short stories, Portraits of a Few of the People I’ve Made Cry, won the 2009 Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction. It was also nominated for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction, won the Ploughshares Zacharis Award and won the Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year Award.

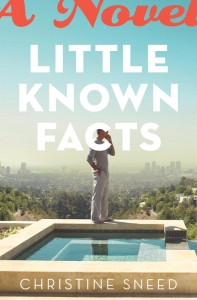

Her new novel, Little Known Facts (Bloomsbury Press) will be published in 2013. Pre-order Little Known Facts here.

CR: During our correspondence, you mentioned that you sent out You’re So Different fifty or more times and rewrote it numerous times. It’s one of those stories I love and seek out. It makes me cringe (still) because it explores that gap between what life might have been and what it has become. After fifty rejections, how did you not become despondent and throw it out? How do you keep faith in a story? Before I started learning about your tenacity (is it partly confidence?), that’s what I would have done.

CS: Unbridled hubris? Or else stubborn persistence. Probably both. Despite the dozens of rejections, a couple of editors at journals that I really respected, AGNI, for example, wrote me kind notes about this story even though they said they weren’t going to take it. AGNI’s editor said, “I’m sure you’ll place this. Just keep sending it out.” His brief, kind note is probably the single most important reason why I didn’t give up on it. It encouraged me to keep submitting Different, and eventually to include it in my collection. I believed from the start that it was a publishable story; I liked it and believed in the characters and the awkward situations that I’d placed them in. It’s been vindicating to have you and a number of other readers tell me that You’re So Different is one of the stories that has stayed with them the most after they finished my book.

CR: The stories in Portraits of a Few of the People I’ve Made Cry stick with me. You never take the easy dig or cheap shot. Your writing is always surprising but carefully crafted (and funny in so many subtle ways that I’m envious). Every sentence fits. Same in what I’ve read of Little Known Facts. You have written five novels before the short story collection was published. How has your approach to writing changed over the years? Or has it? And what happened to those other novels?

CS: My approach to writing has stayed the same since I started writing seriously about twenty years ago – sit down at my desk and whether or not I’m worn out from other things I’ve done that day or from poor sleep the night before or a pile of other tasks clamoring to be done, I make myself to stay at my desk until I’ve written a few paragraphs, or a few sentences, at the very least, that are worth saving. I might go back the next day and see that I wrote something cruddy and start that section over, but that’s okay. I remember reading an interview with the story writer Mary Yukari Waters in Glimmer Train a couple of years ago where she said that being a writer is like being on a lifelong diet – you feel this tremendous guilt if you don’t write, just as you would if you cheated on your diet. I know exactly what she means. The days I don’t write, I usually feel pretty anxious and guilty. So I write. You have to say no to a lot of things, and you have to be committed to your craft and enjoy it enough not to feel like you’re missing out too much on the things you say no to. You have to love writing as much, or more, than anything else. Obvious as it may seem, that’s one of the biggest differences between a writer and a non-writer.

As for the unpublished novels, I try to think of them as stepping-stones on the way to the two books I’ve published or will soon publish, in the case of Little Known Facts. They helped me learn to write better, for one, and I don’t regret spending the years on them that I did. Of course I wish they had been published, but they weren’t, and so that’s more or less that. Two of them probably weren’t good enough, anyway. I think we have this idea, and our media whips us into a frenzy over it, that everything we do should be used to promote our own glory – it should all be publishable, it should all be out there, but that’s not true. If you asked an artist if she wants to put every single canvas she’s painted on the walls of a gallery or a sculptor the same questions about his work, I’m pretty sure they’d both laugh very loudly and say, “You’re kidding, right?”

That’s the same with writing – not every story or novel I’ve written is good enough to deserve to be published. I worry about the trend with e-publishing and people racing to Amazon or other e-publishers with their work when I’d have to bet that a lot of it isn’t even close to being ready for readers. Why the rush? I say this all the time, something a friend said to me a year or two ago – but it’s true and we need to be reminded: This is a marathon, not a sprint. If you’re a writer, you write and keep writing until you have before you the best work you can imagine producing, and then, you hope, though it’s not guaranteed, that a publisher and the accolades will follow.

CR: After 18 rejections, Quality of Life was published in 2008 Best American Short Stories. You mentioned that you were “shocked and worried, too, when I got the call that it would be in BASS because I didn’t think it was very good.”

But Heidi Pitlor and guest editor Salman Rushdie thought it was good enough to publish next to T.C. Boyle and Alice Munro and Tobias Wolff, among others. Can you talk about looking at your own work with a critical eye (but not too critical) and coming to terms with it? Or do you ever come to terms with the way a story turns out?

CS: By now I’ve written probably about a hundred and twenty or thirty, (maybe more, I’m not sure) short stories, and so I can get a feel pretty quickly, as I’m writing a story, whether it’s working. This is a critical faculty that’s taken me a long time to develop, but by now, after writing thousands of pages of fiction, and also, reading probably a few thousand student stories since I began teaching creative writing in 1995 as a graduate student at Indiana University, I have a pretty good sense of what works and what doesn’t in a short story. I’ve put in my ten thousand hours, probably two or three times that, Mr. Gladwell. You just know, I guess, after a while. Like knowing when it’s art and when it’s pornography. This is another reason why it’s hard to be a writer over the long-term – you have to deal with uncertainty and doubt on so many levels – self-doubt most aggressively, but also, doubt about why editors reject some of your stories but accept others, and doubt about whether you will ever earn any money from your work or get the respect of your peers or love or whatever it is you’re hoping your writing will deliver to you. You should have some idea of what you want from your writing because once things start coming to you, they might not be at all what you expect. You have to be honest with yourself, but I don’t think that self-knowledge is very welcome, not in our present-day instant-gratification society, usually because what we’re learning about ourselves is so embarrassing and/or unnerving.

I thought, regarding Quality of Life as I was sending out, “This is a decent enough story.” But then when NER accepted it and later when it was plucked out of NER and chosen for BASS, I started sweating. “I’m going to be with Very Big Writers in BASS. Do I really know what I’m doing? Maybe this is all a fluke.” I think it’s okay to feel this way – it keeps you grounded. I know that I can write a good enough story now, but I also don’t know how good it is, especially compared to someone like Alice Munro or Deborah Eisenberg. I had another story chosen for the 2012 PEN/O. Henry anthology last year and I had a similar reaction when Laura Furman, the series editor, emailed to say she’d chosen The First Wife (another story first published in NER – I love them!) I thought, “Is she sure it’s good enough?” But again, I do think that some self-doubt is good – it makes me try to be better with each new story or chapter I write.

CR: You’re right. Pornography can be tricky. I always judge it on the witty repartee.

You sent out A Million Dollars 25 times. Thea and her family were the subject of a longer work you gave up on when two different agents told you they didn’t think it was publishable. You no longer show agents your work-in-progress. You’ve learned that, perhaps, you’re ‘pigheaded’ and want to prove them wrong. In this very shifty publishing climate, why have you chosen to not show agents your work-in-progress?

CS: It’s very easy to get discouraged if an agent says something like, “Well, I don’t know. I’m not sure if this is working yet.” She’s not sure if it’s working yet – a word that isn’t an absolute, but a writer (or at least I) will often take this to mean, “This stinks. Are you serious? This will never work.” I’d rather have an entire first draft completed and see how it works or doesn’t work holistically and then tackle the revision, rather than worry that I’m wasting my time on a doomed project as I’m writing it. And to be frank, most agents don’t want to read works-in-progress. Mine doesn’t. She’d rather see the whole draft too, and be able to consider all of the decisions I’ve made and go from there, whether a lot of revision is needed or not.

CR: I’ve read the chapters of Little Known Facts published in The Southern Review and New England Review. How does writing a novel differ from writing a short story? What are the similarities?

CS: I approached the writing of LKF the same way I approach story writing – I wanted to create a narrative arc in each chapter that felt to me like a story’s, and this also helped me to focus on character and the compression of the plot arc that a successful story requires, unlike a novel. Some of the chapters, as a result, are stand-alone, but most of the later ones are not. I had to tie up more threads in the later chapters, ones introduced in the earlier chapters, but I still wanted these later chapters to feel as tight and confiding and urgent as the early ones.

CR: You said that writing LKF was a ‘euphoric’ experience. The characters are so real and organic — even under the microscope of fame. Our society has such a love/hate relationship with celebrity. Often, they seem like charming animals at the zoo. But this novel digs into the satellite characters orbiting around the celebrity and the celebrity himself. They aren’t thin, cardboard cutouts. You seem to have an inside scoop. How did you research the novel? How did the research surprise you? Did it lead you to places you didn’t originally envision?

CS: I didn’t do a whole lot of research for this novel; much of it I really did imagine – e.g. what would it be like to be the son of someone like Harrison Ford or Paul Newman? What would it be like to be married to Ford or Newman or Brad Pitt or George Clooney? I’m sure that you also do this as a fiction writer – it’s one of fiction’s greatest pleasures – imagining how it would be to inhabit someone else’s consciousness. I had to ask a few physician friends for the particulars about the chapters having to do with the MD characters, and I asked a generous friend who has worked in Hollywood for a long time to read through the manuscript to make sure that I hadn’t gotten the movie-related details wrong. I don’t know if there are still some minor errors, but nothing too big, I hope. Frankly, there weren’t many surprises about the details I learned from my friends in Hollywood and in medicine. I had already come across most of these details because I’ve been a movie fanatic for so long. I’ve watched the Oscars for many years, kept minor tabs on some actors’ career trajectories, and have read about filmmaking and actors for many years. This was my ideal subject, and it’s probably one reason why this is the first novel I’m publishing. Add to it tricky, often guilt-plagued family relationships, and this was exactly what I’d always wanted to write about.

CR: I often wonder what it would be like to be married to Steve Buscemi…but that’s an entirely different issue.

LKF begins in a close third person from Will. Will is the son of the insanely famous celebrity Renn Ivins. The rest of the novel unfolds in close third person and first person tellings. Is that the way you envisioned it? Did you think, initially, that the entire story would be told from Renn’s point of view?

CS: I wrote the first chapter of LKF several months before I wrote chapters 2 – 11 because initially I thought Will’s chapter would be a stand-alone story and that would be it. But for some reason that I can’t now recall, I realized that I had more to say about Will and his family and wanted right away to write a multi-POV novel. It was like this from the beginning, well, from the second beginning – after I realized that I wanted to expand Will’s story into a novel that would allow me to write from the perspective of the other people in his life who are important to him. I knew that it wouldn’t be from Renn’s POV alone – it wasn’t even a question. I liked instead the idea of his character taking shape through everyone else’s POV before readers actually hear from him (his chapter is #8.)

Little Known Facts (Bloomsbury Press) will be published in 2013. Pre-order it at http://www.amazon.com/Little-Known-Facts-A-Novel/dp/1608199584.

Christine Sneed teaches creative writing at the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign and Northwestern University. Her books include the story collection, Portraits of a Few of the People I’ve Made Cry, which won the 2009 Grace Paley Prize and Ploughshares Zacharis Prize for a first book, and the novels Paris, He Said and Little Known Facts, the latter of which was a Booklist top-ten debut novel of 2013 and won the 2013 Society of Midland Authors Award in adult fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Best American Short Stories, PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories, Ploughshares, Southern Review, New England Review, and a number of other journals.

Christine Maul Rice’s award-winning novel, Swarm Theory, was called “a gripping work of Midwest Gothic” by Michigan Public Radio and earned an Independent Publisher Book Award, a National Indie Excellence Award, a Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year award (finalist), and was included in PANK’s Best Books of 2016 and Powell’s Books Midyear Roundup: The Best Books of 2016 So Far. In 2019, Christine was included in New City’s Lit 50: Who Really Books in Chicago and named One of 30 Writers to Watch by Chicago’s Guild Complex. Most recently, her short stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Allium, 2020: The Year of the Asterisk*, Make Literary Magazine, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Millions, Roanoke Review, The Literary Review, among others. Christine is the founder and editor of the literary nonprofit Hypertext Magazine & Studio and is an Assistant Professor of English at Valparaiso University.