By Christine Rice

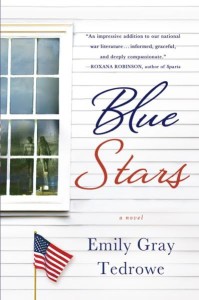

In her novel Blue Stars, Emily Gray Tedrowe’s gaze scans the battlefield but rests on the struggles of those left behind.

Tedrowe fully imagines two women whose soldiers have been deployed to Iraq: the mother of a Marine, and the wife of an Army reservist. The mother, Ellen Silverman, is a well-steeped academic. She’s staunchly against the U.S. invasion of Iraq and is caught wholly off guard when her ward, Michael, informs her of his plan to become a Marine. Like many of us, she hadn’t truly thought beyond the political to the personal realities of war.

Lacey Reed Diaz is a personal trainer and the wife of U.S. Army Reservist Eddie Diaz. Lacey knows the score, she’s been through deployments before. All the same, she’s still ill-equipped to face single parenthood, loneliness, financial stress, and the messiness of her own desires.

After meeting Emily at Ragdale last fall, I read both of her novels. Her first, Commuters, delves into the reconfiguration of family in a much different setting than Blue Stars. In both novels, however, Tedrowe masterfully reveals the emotional depth of her characters and the desperate situations in which they find themselves.

Christine Rice: There are some really wonderful memoirs and essay collections by women soldiers. There are also more and more novels and short story collections written from the soldier’s point of view by authors like Marriette Kalinowski’s The Train, Siobhan Fallon’s You Know When the Men Are Gone, Bobbie Ann Mason’s In Country, Katey Schultz’s short story collection Flashes of War, M.B. Wilmot’s novel Quixote in Ramadi, Karen Houppert’s Home Fires Burning.

But there aren’t many novels told from the experience of those left behind – those left to carry on during a soldier’s deployment.

How did the idea of this book, these characters, find their way to the page for you? From reading ACKNOWLEDGMENTS, I gathered that your brother is a Marine.

Emily Gray Tedrowe: You’re right, my younger brother served as a Marine in both Afghanistan and Iraq. On the one hand, my idea for this novel comes directly from that experience, of having been part of a military family and thus having spent time on the home front while a loved one was away at war. (“Home front”: such an interesting phrase to me, with its archaic feel as well as the acknowledgment that there is fighting, of a kind, even as you wait at home in safety.) On the other hand, while my brother was actually deployed, and even after his safe return, I was sure that I would never write about war. I just didn’t know if I wanted to go there, emotionally, on paper, after having gotten through the lived experience of that anxious waiting and waiting and waiting. But what happened is that I got interested in what other families go through, particularly as I was following the Walter Reed housing scandal fallout in the news. That opened me up to considering what it must have been like for other women (not all women, certainly there are male as well as female partners of women service members, but mostly it is women) who had a much more difficult time than I did, in that they had to negotiate the terrible shifting uncertainties of their loved ones being injured. I kept thinking about the many women who went to stay – and essentially live – at Walter Reed while their soldier recuperated from limb loss or head trauma. What was it like for them? How did they cope with the uncertainty, with the dislocation, with the sheer strangeness of leaving your life for an unknown period of time? Once I hooked into those “what if” questions, I found my way to characters who were living those experiences.

CR: Blue Stars deals with the collateral damage of war on the home front and how the people left behind—the wives and parents and siblings and children—carry on in the soldier’s absence.

There’s this interesting piece by Ryan Bubalo in the Los Angeles Review of Books. In it, he points out that what happens after the war is the situation. And that’s what these characters seem to face: the situation.

The amount of research you put into Blue Stars (that makes it feel so authentic and sympathetic) seems staggering. It might have frightened off lesser writers. I mean, you had to get to the bone of the situation in a lot of ways and that had to have taken so much reading and research and listening. Was there ever a moment when the research steered you in a different direction than what you had originally envisioned? Where the story shifted based on what you uncovered or learned? If so, how did you deal with that shift, that kind of shattering of what you thought a story might be or be about, on the page?

EGT: I do love that term “the situation” because it gets at the utter vagueness of ALL the factors at work in what life is like after war. So much is shifting, so much is confusing. “The situation” seems to capture that well. And thank you for saying that about the research. It’s funny, though, because when I’m deep into a writing project nothing about the work involved in learning seems to me like “research” at least how I understand that term in my scholarly work. It’s more like an obsession or following a hunch or being intensely curious. The way it works in my mind is that I want to see and hear as much of the surrounding environment as my characters would, so that I can eventually know how they felt, and what they’d say or do, in those circumstances.

I do like to physically go to a place that I’m writing about, to walk around it and soak in the sights and smells. I did make it to Walter Reed, but not before the base was closed – and that ended up being somewhat of a debacle-slash-blessing in disguise (that I wrote about here, if you’re interested). Whenever I was reading books about the war, or spending hours and hours in the Pritzker Military Library in Chicago, or watching documentaries, I had that goal first and foremost: what would my characters think of this moment, how would they react, what if this was happening to them.

CR: That’s interesting that you said that, once you’re in a writing project, the “work involved in learning” doesn’t feel like research. I think that’s very true. I guess it’s more about how you go about writing a story.

I love Edith Wharton and was delighted that you wove her into the narrative on so many levels. Wharton — who stayed in Paris during World War I instead of fleeing to a safer city — wrote quite extensively on and about war in her fiction and essays. She also wrote opinion pieces, sent to American newspapers, criticizing America’s initial stance on getting involved in World War I.

Ellen Silverman, one of the main characters, is a college professor and Wharton scholar and, at the beginning of the novel, shares that space very much removed from war, and ‘the situation’ of war, and the problems associated with being left behind. She is pretty representative of most of America (it’s estimated that less than .05 percent of Americans now serve in the military compared to 12 percent during World War II). At the beginning of the book she is self-aware her ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality but as the story develops, she is forced to deal with this privilege.

How did Ellen Silverman’s character develop? Were you a fan of Edith Wharton before writing Blue Stars? Or did this connection grow out of the narrative?

EGT: I knew that I wanted Ellen’s character to be a lit professor right from the start, to amplify exactly what you point out — her privileged place of not having had to deal with war on a first-hand basis before, which is how so many people in the US experience it — as “news” but not as actual repercussions in your home. I wanted to have her face the shock of that changed status right in her own life. So I thought the contrast of “ivory tower” with the “real world” would be a good place to explore.

And then when it came to decide her specialty, I thought, oh, she should be working on a topic that is all drawing rooms and veiled insults of the Henry James kind. I think I chose Edith Wharton more out of a misplaced stereotype based on her own wealth and from novels like The Age of Innocence. And because I do love her work, so I knew it would be fun for me to get the chance to read up on her. And then the joke was on me, because the more I learned about Wharton (via the brilliant Hermione Lee biography), the more I found out about Wharton’s utter activist stance in terms of World War I, how she knew the fronts intimately, and how her war work (and novels) were such a big part of her life. Then those connections began to get woven into Ellen’s experience, and I found that a really happy accident in the writing of the book.

CR: That’s amazing. I love that story. Before I read Edith Wharton’s ghost stories and essays, I always thought of her as ‘that author who wrote The Age of Innocence‘ too. She’s an excellent example of a woman, a writer, being judged (for years) by a male jury…and that male jury influenced the way many of us read her for many years.

In the United States, banners scream ‘Support Our Troops’ but, in reality, most politicians and U.S. citizens are insulated from truly understanding and supporting the troops. Even my dad, who fought in many of the biggest conflicts of World War II, couldn’t get prescription coverage from the VA. They made it so difficult that it proved impossible. The breadth and scope of these kinds of stories keep being revealed (and now, because of people with the bully pulpit like Samantha Bee, the heightened hurdles women soldiers face seem especially frustrating).

EGT: God bless Samantha Bee, right? I mean, I would not be able to endure this current political climate without her and John Oliver and Louis CK and so many others who use humor to shine a light on the outrageous.

CR: You credit Washington Post reporters Dana Priest and Anne Hull for their Pulitizer Prize winning investigative reporting on the conditions at Walter Reed as inspiration for this novel. Can you talk about how their work inspired Blue Stars? About how this reporting, from 2007, still resonates?

EGT: Yes, the Priest/Hull reporting was essential to my novel, especially once I realized that so much of it would take place in the “old” Walter Reed. As I said earlier, I was fascinated by their series in the Post when published, and by then all the fallout afterward. I think one reason I was so captivated was because of their focus on not just what the injured soldiers were going through, in those substandard conditions, but on what the families had to cope with also. They spent so much time and effort telling us about the wives and mothers of the soldiers in Building 18, and how maddening it was to have to try to find services and care in that vast overflow of outpatients on the hospital campus. To me as a citizen, it felt important to hear these stories about the way war reaches deep into families long after the soldiers come home. As a novelist, I found it really inspiring, and wanted to create characters who could have been part of the scene that Priest and Hull witnessed in their visits to Walter Reed.

CR: There is this palpable tension in the book between the majority of Americans who easily wear buttons that say ‘Support Our Troops’ and politicians who do the same through lip service but don’t pass legislation to really support the troops.

Lacey, whose husband Eddie is an Army Reservist serving in Iraq, is one of the few who really does ‘support the troops.’ But after Eddie is deployed, she barely hangs on. She’s a wonderfully flawed and complex character. Can you talk about Lacey’s development on the page?

EGT: Honestly, I loved writing Lacey’s scenes. I loved her anger, her righteousness, her mistakes, her big heart. When I first thought of Lacey, my notes said something like, “takes up a lot of space.” Physically – she’s a big, sexy, messy woman. Also emotionally, because she doesn’t hold back. And I think that comes into play most when she’s feeling outraged on behalf of the US military. She’s like a lot of people I know in that she keeps completely up to date on the minutiae of the situation in Iraq, she has searingly strong opinions and isn’t afraid to share them, and she’s got an ax to grind. I loved giving voice to some thoughts that I personally have had, about how we as a culture so often have the luxury to ignore the service that keeps us free, and how a certain sector of the population (those of working class background primarily) are given this huge burden to carry on behalf of all of us. That stuff can infuriate me too, so I gave it free rein in Lacey’s voice and persona. I also really like that Lacey makes mistakes — big ones. We all do; we hurt people and we do dumb things. Lacey does those in a big way, so there was a sense of pleasure for me in creating her flaws as well as finding her sweetness.

CR: There’s also this guilt that dogs parents, partners, siblings, kids. After Lacey finds out about Eddie’s injuries, you write:

Inside, though, Lacey listened to a voice calmly explain why this had happened. You did this to him, it said, You made it happen.

CR: The soldier’s absence puts a kind of sharp light on relationships — defining strengths and weaknesses. You really captured that on the page in Blue Stars and in your first novel Commuters. You have a sharp eye for the intricacies of relationships. What draws you to this kind of material? To really dig into family dynamics and relationships?

EGT: Thank you! I don’t know what to say other than I am completely fascinated by the microcosm world of the family. I love the shifting relationships, the different generations, the alliances that change and renew and nourish over time. Novels dealing with this material are the ones I am inevitably drawn to. And my main dictum to myself is “write what you’d like to read.” I fall back on that at the level of the sentence, the scene, the chapter. Whenever I’m in doubt, I remind myself to write the page that I would want to read, if I had picked up this novel.

CR: I’m curious about the reactions of readers whose loved ones are in active duty. It seems like you really captured the poignancy of parents and partners dealing with war and its effects in Blue Stars. Did others feel that way?

EGT: I’m curious too! I’m not one for reading reviews on Amazon or GoodReads (frankly, staying away is key to my mental health as a writer). Though I have had some wonderful responses at readings, when people have come up to me and said that I captured their world really well, the world of being in the military, or in a military family. That means a lot to me, of course. And I have several family members who are currently serving, or married to someone who is. One of them, my cousin’s wife actually, read the manuscript in draft and gave me a lot of encouraging support and some fact-checking — both were hugely appreciated. I can understand, though, if there is pushback or uncertainty from the some military wives. That is an incredibly tight community — as it should be! — and they are wary of “outsiders” who claim to speak for that experience. I get it. All I can say is that I listened hard to what I heard people tell me about being “married to the military,” I did my homework, and I approached telling this story with as much empathy and honesty as I could.

CR: There’s this really fascinating article about how fiction ‘enlarges men’s sympathies’ by Jonathan Gottschall in The Boston Globe. Here’s an excerpt:

This research consistently shows that fiction does mold us. The more deeply we are cast under a story’s spell, the more potent its influence. In fact, fiction seems to be more effective at changing beliefs than nonfiction, which is designed to persuade through argument and evidence. Studies show that when we read nonfiction, we read with our shields up. We are critical and skeptical. But when we are absorbed in a story, we drop our intellectual guard. We are moved emotionally, and this seems to make us rubbery and easy to shape.

But perhaps the most impressive finding is just how fiction shapes us: mainly for the better, not for the worse. Fiction enhances our ability to understand other people; it promotes a deep morality that cuts across religious and political creeds. More peculiarly, fiction’s happy endings seem to warp our sense of reality. They make us believe in a lie: that the world is more just than it actually is. But believing that lie has important effects for society — and it may even help explain why humans tell stories in the first place.

Gottschall later writes:

So those who are concerned about the messages in fiction — whether they are conservative or progressive — have a point. Fiction is dangerous because it has the power to modify the principles of individuals and whole societies.

But fiction is doing something that all political factions should be able to get behind. Beyond the local battles of the culture wars, virtually all storytelling, regardless of genre, increases society’s fund of empathy and reinforces an ethic of decency that is deeper than politics.

With this in mind, which leaders would you dump on a deserted island and, as a condition of their rescue, make it a requirement to read Blue Stars?

EGT: Wow, I love these passages so much. I couldn’t agree more about how imagining what life is like for others is what fiction does best. And how great is it that in doing so, it’s not only morally essential, but completely entertaining? As far as which leaders… I wouldn’t presume to force my novel on anyone, although God knows if it made it’s way to President Obama I would probably ask for nothing more in this writing life. But frankly I don’t worry about his qualities of moral imagination and empathy.

Blue Stars was recently released in paperback. Find it HERE or at your favorite indie book store.

Christine Maul Rice’s award-winning novel, Swarm Theory, was called “a gripping work of Midwest Gothic” by Michigan Public Radio and earned an Independent Publisher Book Award, a National Indie Excellence Award, a Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year award (finalist), and was included in PANK’s Best Books of 2016 and Powell’s Books Midyear Roundup: The Best Books of 2016 So Far. In 2019, Christine was included in New City’s Lit 50: Who Really Books in Chicago and named One of 30 Writers to Watch by Chicago’s Guild Complex. Most recently, her short stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Allium, 2020: The Year of the Asterisk*, Make Literary Magazine, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Millions, Roanoke Review, The Literary Review, among others. Christine is the founder and editor of the literary nonprofit Hypertext Magazine & Studio and is an Assistant Professor of English at Valparaiso University.