By Christine Maul Rice

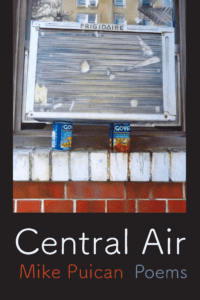

As a longtime Chicagoan, reading Mike Puican’s debut collection, Central Air (Northwestern University Press), felt like reacquainting myself with a dear friend. Here’s the Red Line, the tracks of which I walk under every day, “…slicing the living night…” There’s “…the top of Sheridan’s horse…” with the sun moving “…in slow increments of dying.” Something’s slightly off, of course, the promise of America and the City of Big Shoulders isn’t as well-appointed—for the majority of its nearly 3,000,000 residents—as the travel books profess. Puican’s sharp eye captures Chicago’s inhumanity, brutality, inequity but also unguarded moments of beauty.

Mike has been advocating for fellow Chicago writers and artists as a longtime board member of Chicago’s Guild Literary Complex and by leading poetry workshops for men who were formerly incarcerated. Mike and I caught up to talk about Central Air, teaching poetry, hitchhiking to Chicago, finding his way as a young man in the city, and how he expresses himself on the page.

How has teaching poetry workshops to men who were formerly incarcerated impacted your writing process?

First, I’ve never taught before working with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated men. Just the act of developing a class that looks closely at poems and preparing for leading discussions with the men have improved my knowledge of poetry. I believe this is one of the reasons why teachers and professors are so smart about the areas they teach. They’ve developed a comfort with and a deep knowledge of the material.

The other profound discovery is that the men in my workshops are no different than anyone we might talk to on the bus or waiting in line at the DMV. Yes, they’ve made mistakes but that doesn’t define them. Far from it. Most of them have moved past that time in their lives and are just doing their time so they can get out and lead normal lives. Before we do any writing, I always give a warmup exercise where they recall something from their lives. It’s usually something fairly mundane. I’ll ask them, for example, to talk about a time where they had a good time with other people. Their stories are real, human, sometimes moving, and often unexpected.

It has opened me up to having a much greater appreciation of people who have made mistakes (who of us hasn’t made terrible mistakes?).

All of us have made mistakes—and I am aware of and check my privilege as a white person. Where law enforcement is concerned, there’s little tolerance for mistakes—especially for many people of color.

How have the events of the past few years impacted your creative process (if at all)? Do you feel a certain urgency to make sense of this time through poetry?

It has intensified the energy behind my writing. Both my wife Mary Hawley and I retired to write full time. Before COVID, I was writing every day but also going out to readings and other cultural events three or four times a week. Starting last March when everything shut down, it gave me the time to focus even more time on writing.

I have spent my life as a poet writing between the cracks of my work and other responsibilities. Now I have been given the incredible gift of being able to write full time. I am determined not to waste it.

Three of the poems in Central Air (“Red Line,” “Immigrant Grasses,” and “Sunset at a Lake”) appeared in our print journal Hypertext Review. These three poems struck me as perfect complements to one another. Did you write these within a certain time frame? Did one suggest the writing of another?

It’s funny but I didn’t see the obvious connections in these poems until you pointed it out when I submitted them. They were started years apart from each other. I think you’re identifying a direction I sometimes take in my writing. These are city poems, specifically poems situated on Chicago’s North Side—on a Red Line L train, in the Uptown area, and in Lincoln Park near Armitage Avenue. They’re all about people leading quirky individual lives. That’s what I hope these poems capture.

Central Air is very much a book about the City of Chicago. Your gaze lands on specific streets and locations. In “Englewood in Bloom,” you write:

He is a giant with the voice of a girl; he

sings. Englewood stands at the window

above the Apostolic Lighthouse church,

dawn striating the avenue and all of its

regular and irregular red townhomes.

What is it about the City that draws your attention? What elements characterize the City of Chicago for you?

I grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania. When I was 19 years old, I hitchhiked to Chicago to discover the big world. It was a reckless move that I was ill prepared for. I had some pretty rough experiences in those early years. It took a good while to get my feet on the ground and find my direction.

Although I’ve been here my whole adult life, I still have the same fascination of that small-town kid. There are a lot of preconceived notions people have about the City—it’s impersonal, congested, dangerous. But like all stereotypes, it overlooks the particular, the real. I love watching how people, despite the challenges of living in the city, still find ways to express their individuality.

There are over nine million people in Chicago’s greater metro area. That means there are nine million people just like me trying to figure things out, trying to make a life for themselves. I get a lot of energy and inspiration from that.

Your poems have a narrative quality. Do you write with a narrative arc in mind or are you surprised by the story that emerges?

That’s a misdirection I use. The details of the various lives in my poems can seem as though I’m telling stories. But these stories rarely go anywhere; they have no plots. My interest is almost always in the lyric moment. The details in the poems are meant to grasp at experience outside that is of time and, frequently, beyond definition.

There are many great narrative poems. It’s just that I’ve never been interested in writing one. What challenges me and excites me is poetry that steps outside of the generally accepted world and tries to better describe the experience of being alive in a specific moment.

I admire how your work focuses on the day-to-day elements of our lives. What is it that draws you to write about these people, these actions? What does poetry about everyday people accomplish for you?

If you think about the things that bind us all together, first, we all breathe the same air. (This is this idea behind the title of my book, Central Air.) In addition, we all have dreams, we all desire to be loved, and we are all trying to make our lives better. I believe this is universal despite the flawed and misguided ways we often go about it.

I feel that everyone is doing the best they can—not the best they possibly could do—but the best they can in the moment. Even the worst person one can imagine is doing the best they know how. It is through this lens that I try to relate to the world. It is at the heart of my writing about myself and other people.

Before Central Air, you tried for twenty years to get a book of poetry published. Your book had been rejected over 145 times before this. Did you get discouraged? What kept you going?

First, let me say that I rarely sent out the same manuscript. I was always revising, reordering, taking poems out, putting others in. In the process of doing that, my work improved. Most of the manuscripts I sent out weren’t ready to be published.

What kept me going is that getting a book published isn’t the only pleasure I find as a writer. There is an entire community of writers and artists to connect with, commiserate with, and to learn from. I’ve had individual poems published, I’ve done readings, and I’ve written poetry reviews. There are lots of ways to engage with the artistic community.

Ultimately, however, the only answer is that you have to love writing. I subscribe to the advice Marge Pearcy gives to writers in her poem “For the Young Who Want to”: “Work is its own cure. You have to like it better than being loved.”

In addition to the poems about the City, a number of poems address religion and spirituality from a non-believer’s point of view—yet they go right to the edge of belief. Some even speak directly to God. Can you comment on these poems?

I am an atheist but, growing up, I was a devout Catholic. I had twelve years of Catholic education. I used to serve as an altar boy at 7 a.m. Mass before school. At some points in my life I wanted to be a priest. Although, for me, God doesn’t exist, I still have a strong longing for the God I used to believe in.

One of my poems ends with “Speak, Lord, I will forgive everything.” There is so much pain and unfairness in the world that it’s impossible for me to believe in a compassionate god. However, if I received some kind of sign that God exists, I would overlook all of that and believe. That expresses my longing for God.

But it’s not a settled feeling. I feel it’s a mistake to simply declare that God doesn’t exist and not think about it again. There is so much mystery in the world. One always needs to be looking at it and interrogating it. No matter what you believe, you should wake up each day and ask if what you believe is true.

You frequently use humor in your poems. There’s even a poem named “Joke” in which you play around with different versions of a joke that begins: “A dog walks into a bar and orders a beer.” Why are you drawn to the use of humor? What does humor bring to a poem?

One reason is that it keeps the reader interested. Sometimes my poems are hard to follow. Humor gives the reader something to hold on to. Also, humor can open the reader up so a serious point has more impact.

My poem “Current” describes vignettes from my life. One line recounts the experience of scattering my parents’ ashes: “One stands on a bluff as his parent’s ashes sift through the trees below.” The next line is much lighter: “One says, I’m stoned . . . I mean starved,” which is something I once said to my mother when I was in high school. Then there’s the line: “He lets go of his father’s hand and sprints into Main Street.” That happened when I was three and I was hit by a car. The juxtaposition in circumstances, time, and tone is an attempt to capture the highs and lows and inconsistencies of my life.

In August, Mike Puican’s debut book of poetry, Central Air, will be released by Northwestern Press. He has had poems in Poetry, Michigan Quarterly Review, and New England Review, among others. He won the 2004 Tia Chucha Press Chapbook Contest for his chapbook, 30 Seconds. Mike was a member of the 1996 Chicago Slam Team, and is past president and long-time board member of the Guild Literary Complex in Chicago. Currently he teaches poetry to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals at the Federal Metropolitan Correctional Center and St. Leonard’s House.

Christine Maul Rice’s award-winning novel, Swarm Theory, was called “a gripping work of Midwest Gothic” by Michigan Public Radio and earned an Independent Publisher Book Award, a National Indie Excellence Award, a Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year award (finalist), and was included in PANK’s Best Books of 2016 and Powell’s Books Midyear Roundup: The Best Books of 2016 So Far. In 2019, Christine was included in New City’s Lit 50: Who Really Books in Chicago and named One of 30 Writers to Watch by Chicago’s Guild Complex. Most recently, her short stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Allium, 2020: The Year of the Asterisk*, Make Literary Magazine, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Millions, Roanoke Review, The Literary Review, among others. Christine is the founder and editor of the literary nonprofit Hypertext Magazine & Studio and is an Assistant Professor of English at Valparaiso University.