By Emily Roth

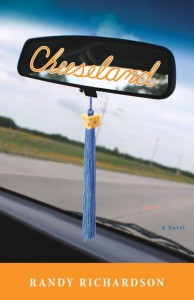

While writing his second novel, Cheeseland, Randy Richardson used fiction as a vehicle to mold ghosts from his own past, transform them into art and examine how a single event can reverberate over time. Cheeseland tells the story of two boys who, after a mutual friend’s suicide, skip their high school graduation, take a road trip to Wisconsin and attempt to rebuild their devastated friendship. Richardson sat down with HYPERTEXT to discuss the journey of writing and publishing this novel — as well as how art can become activism.

Cheeseland is available for purchase in e-book form, and paperbacks are available for purchase through Eckhartz Press. And check this out: one dollar from every soft-cover book sale will go to the non-profit suicide prevention initiative Elyssa’s Mission.

HT: How did you find Echartz Press?

Randy Richardson: I’m not so sure that it wasn’t a case of Eckhartz finding me more than me finding them. Eckhartz is a small independent publisher that Rick Kaempfer and David Stern launched in Chicago about a year ago. I’d known Rick beforehand. We’d both contributed to the Cubbie Blues anthology and we shared many common friends, interests and experiences, not the least of which was that we were both long-suffering, die-hard Cubs fans. Rick is also a member of the Chicago Writers Association, a group to which I serve as president. He attended one of our events and tapped me on the shoulder. He had heard through the grapevine that I was shopping a manuscript, and asked me how that was going. Well, I told him it wasn’t going all that well, and he then asked me if he could take a look at it. I of course said yes, and a couple months later he asked me if he could publish it. From the day Rick asked to see my manuscript until the day Cheeseland was released was about six months. It all happened very fast, which is not the norm in the publishing world.

HT: What were some of the differences between the publishing process for Cheeseland and for Lost in the Ivy?

RR: Lost in the Ivy, my first novel, was a much different publishing experience. It’s a long story in itself, filled with rejections, disappointments, mistakes, and even death. The death part was quite tragic. I was scheduled to meet a small mom-and-pop publisher, and the night before I was to travel to meet with them, I got a call from the pop that the mom had died, quite unexpectedly, and that the pop wouldn’t be continuing the business. The biggest disappointment was with a bigger indie press that rejected the manuscript at the last level after reviewing it for six months. The mistake was giving up at some level after all of those disappointments and making the choice to publish with a POD publisher that claimed to be something that it wasn’t. That was a tough lesson to learn, but I really don’t regret that it happened. I always take such lessons as exactly that, lessons. We learn from them, hopefully, and don’t make the same mistakes. This is another reason why it is helpful to have the support of a writing community, like the Chicago Writers Association, where you can learn and share information with one another so that others don’t make the same mistakes.

HT: Were you met with any opposition from your publishers regarding any decisions you made in the novel? Did you change anything at their request?

RR: I can’t say that I was met with any opposition, but David Stern, Rick’s co-publisher, did express serious concerns about the ending of the first part of the book. That first part ends with an auto accident, and, in the original submission, I had not addressed at all what happened with that accident when the two characters meet again in part two, which is set thirty years later. After that meeting, I went back and looked at it again, and he was absolutely right. That was a gaping hole I had totally missed, even after several edits. I added a scene to the second part that hopefully not only fills that hole but that also gives more depth to the character and why he is the way he is.

RR: I can’t say that I was met with any opposition, but David Stern, Rick’s co-publisher, did express serious concerns about the ending of the first part of the book. That first part ends with an auto accident, and, in the original submission, I had not addressed at all what happened with that accident when the two characters meet again in part two, which is set thirty years later. After that meeting, I went back and looked at it again, and he was absolutely right. That was a gaping hole I had totally missed, even after several edits. I added a scene to the second part that hopefully not only fills that hole but that also gives more depth to the character and why he is the way he is.

Other than that one scene, Rick and Dave were both fully supportive of everything in the novel, even though it tackles some serious and sensitive issues. I think one of the benefits of working with a small, independent publisher is that they’re willing to take more chances than the big publishers might be willing to take. They don’t come in with a preconceived notion of what it is that the audience wants to read. They let the readers decide for themselves what they want to read.

HT: I know that you worked on this novel for several years. Can you elaborate a bit on your daily writing process and how you fit novel writing into your daily life?

RR: Like just about everybody else, time is probably my biggest challenge. I have a day job as an attorney, I have a volunteer job as president of a 400-member writing community, and I have a family. I have to squeeze in writing whenever I can. Lunch breaks. Late at night, after everyone else is asleep. I also give up a lot of things I used to enjoy, like TV and movies. The reality is that my family and my job have to come first, and there isn’t a whole lot of time left over for writing. Fortunately, for me, I don’t have to make a living as a writer. That’s what my day job is for. I write for the love of writing. I honestly don’t think I could make a career as a writer. I’m much too slow. I am always amazed at these authors who are able to crank out a novel every six months. Both of my novels, from start to finish, took about seven years. My son was just a baby when I began writing Cheeseland. It was released just a few days before he turned 9.

HT: How many drafts did it go through?

RR: It is difficult to calculate how many drafts to Cheeseland there were. I wrote it entirely through a critique group, so each chapter was being dissected as I went along. I can tell you that the novel as I initially constructed it began with what is now chapter 7, which is loosely based on an incident that actually happened to me when I was a teen. But before I began shopping the manuscript, all 28 chapters went through the critique group and then a professional editor. Once it got to Eckhartz, it went through Rick and Dave and then their editor. Along the way there were many, many parts that were revised, moved or tossed out.

HT: Chapter 7 was one of my favorites because of the intensity of it, and the way it starts (with the protagonist, Daniel, waking up, disoriented, after a car accident) is so jarring. Did you have any trouble distancing yourself from the event that inspired this and writing it as fiction?

RR: Actually, I didn’t have any trouble distancing myself from that event because I honestly don’t know what really happened. The incident in question, as it played out in real life, involved my friend driving my car into a parked car after a rock concert. I was unconscious in the passenger seat when it happened. I have no idea how we got to where we ended up, which was about 20 miles from where we started. I have these hazy memories of the owner of the other car yelling at my friend for hitting his car while I lay there bleeding, and my friend trying to tell this guy that I needed help. I was very fortunate that the only physical injuries I incurred were some minor cuts and abrasions to my forehead, which had struck the windshield when the car crashed into the parked car. That entire scene gnawed at me for thirty years and developed into Cheeseland. Of course when you write fiction that is even loosely based on real life, you have to always remind yourself to not stray too close to real life. The reality is that my real life isn’t a page-turner, so it’s pretty easy to distance myself from it when I’m writing fiction. I use those real-life experiences purely as inspiration to takes me places that you I never go, and sometimes never would want to go in real life.

HT: At what point in the process of writing the novel did you know that Cheeseland was a story that would be told in two parts, from two very distant points in time?

RR: The seed for the second part wasn’t conceived until I was well along in the process of writing the story. I don’t work from an outline, but instead have a general notion of what I want to write in my head and sort of dive in and see where that idea goes. But that second part of the story is really a reflection of the length of time it took me to write the novel and how I was changing. As I mentioned, I was learning how to be a parent as I was writing this story, and it occurred to me that it would be interesting to see how (or if) these two characters would grow as they became older. I separated them by thirty years because that was how long it had been for me since I was a teen.

HT: What was the most surprising moment for you while writing?

RR: That’s an easy one: The scene where Buck is preaching at the church. That whole sermon came out of a place that I didn’t know I had in me. I’m not at all a religious person. I never go to church. And yet I found myself writing this intensely emotional sermon that spilled out of me one night. To me, that is the fun of writing – finding something in you that even you didn’t know existed.

HT: I think it’s great that you donate some of your proceeds to Elyssa’s Mission. At what point did you realize that your novel could be used to raise awareness about teen suicide? What do you perceive to be the line between art and activism?

RR: While Cheeseland was inspired by a real-life event, thankfully suicide is not part of my own personal story. The first draft of the book didn’t begin with a suicide, it began much later. After reading that first draft, I looked at these two characters and I wanted them to confront an issue that would really impact them and make them look at their lives and their friendship in a different way. That led me to write that opening scene where the two teens have to attend the funeral of their friend who had committed suicide. When I wrote that scene I didn’t initially write it thinking that I would be using it as a platform to raise awareness about teen suicide. I was simply writing a story. But then, someone who had lost a friend to suicide read it and it had a strong emotional impact on her. It was at that point that I saw that there was an opportunity to use my story and make a tangible difference, to go beyond the words and to have something truly positive come from the novel. To me, art can and should entertain. I hope my novel does entertain. But I think the best art, the art that is most lasting, is the art that also educates and makes you really think about the world we all live in and maybe think about it a little differently.

An attorney and award-winning journalist, Randy Richardson was a founding member and first president of the Chicago Writers Association. His essays have been published in the anthologies Chicken Soup for the Father and Son Soul, Humor for a Boomer’s Heart, The Big Book of Christmas Joy, and Cubbie Blues: 100 Years of Waiting Till Next Year, as well as in numerous print and online journals and magazines. His second novel, Cheeseland, came from Eckhartz Press in 2012. Eckhartz is publishing an all-new edition of his first novel, The Wrigleyville Murder Mystery, Lost in the Ivy, in the spring of 2014.

Emily Roth is a native of Kalamazoo, Michigan, and recent graduate of Columbia College Chicago’s BFA in Fiction Writing program. Her writing has appeared in the Story Week Reader, Backhand Stories, Echo Magazine, and HYPERTEXT.