By Christine Rice

In the mid-1980s, I was assigned journalist and historian Frances FitzGerald’s Fire in the Lake, a book that won a Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction, a National Book Award, and the Bancroft Prize. One of the first major books about the Vietnam War written by an American, the book upended me. Of it, Stanley Hoffman wrote in the New York Times:

Miss FitzGerald, a young American freelance writer who has spent much time in Vietnam during the past six years, has written partly a history of South Vietnam, partly a study of American policy there, and partly an account of what this policy has done to a people we have destroyed in order to save from Communism.

Fire in the Lake shifted my worldview and my (until then) unwavering sense of American rightness. I went on to read Dispatches by Michael Herr, A Rumor of War by Phillip Caputo, among other books about our country’s involvement in Southeast Asia.

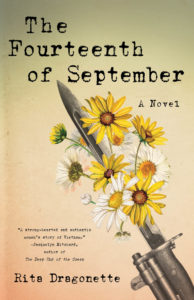

The long tradition of writing about war – by writers of all genders and from writers from all countries – has served to reveal the horror and lasting generational effects of conflict. But few writers have focused on the battles being waged on college campuses during that time. And that’s where Rita Dragonette’s gaze lands in her debut novel, The Fourteenth of September. Dragonette dissects the life and death stakes of a generation: those fighting and dying and those protesting against the United State’s involvement in Vietnam. The Fourteenth of September is also a time-capsule study of feminism – of women’s place at the table of protest – and more broadly, a ‘coming of consciousness’ story of a generation.

Rita Dragonette and I discussed our common bond of a parent who served in World War II, how she fictionalized her personal experience, her extensive research process, #METOO, the impact of Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried on her work, among a few other topics.

Christine Rice: Your mother served as a nurse in World War II. How did your mother’s service and, if she shared them, her stories, influence you as a writer?

Rita Dragonette: My mother kept incredible scrapbooks, so when each of her children were old enough to appreciate them, the questions began. They were only answered very narrowly, as if nothing was a big deal. It was as if it just wasn’t seemly to discuss. Later she explained that when they came back from overseas, no one wanted to listen to what they’d been through, so they didn’t talk about it. Interestingly, both parents would clam up if our reactions weren’t what they expected. For example, all three of us asked separately about a photo where people from my mother’s unit were hanging out of windows, smiling as if watching a sporting event. When I asked what was going on in the picture, she tittered a bit and said, “We were watching them shoot Germans.” We were appalled. She was annoyed at the naiveté of our response, saying, “There were a lot of things that happened right after the war, and we thought the Germans deserved it.”

As a result, I always felt there was a huge untold story, and I wanted to get to the bottom of it. Shortly before she died, I tried to write a memoir of her experiences. After months of interviews where I was painfully pulling details out of her, she flatly refused to go on. I realized two things: if there were a story, I was never going to hear it, and that my mother either didn’t observe at the level I felt I would have, or that she wouldn’t let herself—a protective device. She was a tough woman with a brittle outer shell that wouldn’t allow her to show or perhaps even feel emotion. I’ve always felt the source of that was in those war years, and I’m fascinated about how war affects women uniquely and how that translates down through their children and so on through the generations. We’ve read a lot about how war impacts men and their sons, but the female side is largely untold. This is a big subject I want to continue to explore through fiction. With The Fourteenth of September I focused on Vietnam, the war of my generation. I have another novel in the works that follows women (American and German) on the ground in Europe during World War II, and the effects on their families as a result.

CR: Capturing time-period detail—the late 1960s—must have taken an incredible amount of research.How did you conduct your research? Interviews? Magazine articles? Newspapers? And how long did the research take before you felt you were living and breathing the 1960s?

RD: The foundation of the story was based upon my own personal experiences when I was on a college campus during the seminal times of the Draft Lottery and Kent State, so I had vivid recollections. At the same time, I realized as I began to write that my memory was not perfect. This was historical fiction and had to be exact. A young woman who wanted to build her credentials as a researcher overheard a conversation I was having with a friend about the book and approached me, offering to help. She turned out to be tenacious and affordable. She not only fact-checked (e.g., I hadn’t remembered the first lottery was the day we returned from Thanksgiving vacation), she helped with logistical issues (e.g., I needed to know how long it would take someone with a low lottery number who didn’t make grades to be called up), and finally, how to introduce new elements to realistically communicate the terror of the times (she researched the weekly body counts for the six-month time frame of the novel, and I used them to punctuate the action.)

Throughout the years, particularly if I was at a writer’s retreat, I’d email her to check a fact, and she’d send articles. I found that it was more useful to support the story with research as I went than to do total immersion upfront. It was too easy to become overwhelmed with information.

Personal interviews gave me a lot of color. Memories of the time seem to come in sharp shards of detail—most men will remember their lottery number and their draft “story” about how they did or didn’t have to “go.” Former activists will often have a signature story. Beyond this, context is often blurry and memories spotty. There was also surprising reluctance among the activists I most relied on—including those my characters where based on. It was an uncomfortable time for a lot of people, and they just didn’t want to go back—shades of my mother. Or maybe there were just too many drugs at the time, and memories really were shot. Today, however, people are reaching back, and they’re more forthcoming. This is a tricky time in our history; perhaps we have needed the fifty-year reflection to look back compassionately.

CR: I vividly remember, as a toddler, standing in front of the television, watching the war. It was the first war to be broadcast into our living rooms and the power of those images, in many ways, shaped my earliest memories. Do you remember those broadcasts? Did you re-watch them? And if so, how did that experience of seeing those images again influence the book?

RD: I was pretty young during most of the war and didn’t regularly watch the news. I vaguely remembered it always being in the background, a drumbeat of dread that never seemed to end. It was how I felt during the Watergate years, when there was this relentless news on in the background on a black-and-white TV, the significance of which was hard to appreciate until Nixon’s resignation. In fact, in my novel my main character thinks to herself, “The war had been going on so long, in one form or another, that she didn’t remember a time without it, and now she had grown up to the age where she would be in it.”

In college, we weren’t allowed to have TVs in our rooms, so we didn’t watch. So it wasn’t the television images that propelled me, though I had a very visceral understanding of the horror of what was going on. I must have taken the images in and somehow retained them, because I recognized them when I watched the Ken Burns documentary.

War images are intoxicating for a writer, I believe. There are so many unbelievable images of what humans can do to other humans that it can get in the way of developing a cohesive, thorough story—easy to string a series of horrors together. Since my story had no war scenes, I kept my research focused. The only footage I watched was around the Draft Lottery because I hadn’t seen it the first time (women weren’t welcome in the dorm TV room that night, as explained in the novel). I was blown away: it was like a game show and extremely tacky with hand-lettered signage and these plastic capsules filled with birth dates thrown into a big canister and mixed up for a drawing to see who would die first. It was chilling. But those images proved very useful for my scenes.

CR: In addition to making this story feel authentic, the cultural details are incredibly important to the way in which the narrative unfolds. Did you have to adjust elements of the plot after uncovering something that didn’t quite fit the narrative? In other words, did the research inform the narrative in ways you originally didn’t foresee?

RD: I had three main issues to deal with as a result of research. One was the time line. I had my researcher lay out all the key dates between September 14 through Kent State, and I was amazed at how much happened within such a short period of time. My character had to believably change pretty dramatically within a period of weeks. In experience, this seemed like a long time. However, in war things are accelerated, and that’s how I decided I had to approach it. I cut a tremendous amount from early drafts that showed the progression of characters at a pace that I originally thought was necessary.

Another issue was the role of women, as I mentioned in the this article. One of the propelling themes is that women were side by side in the fight on this campus “battlefield” but felt pretty disenfranchised and often undermined because their lives weren’t at stake and they “couldn’t really understand.” In research, I found that elsewhere women had actually been in charge of much of the antiwar movement and felt respected and empowered. After a lot of angst, I ended up acknowledging that although there were always strong and vocal female leaders, the tremendous sexism of that early-feminist era intimidated many others. And sometimes that intimidation—as in my own case—was self-imposed. And my story was about the latter.

Finally, and I think this happens to many writers, the initial research process was almost paralyzing. I felt I had to include every aspect of what was going on at the time. In early drafts I had a subplot about a character who had an illegal abortion, and I wondered how to include the entire civil rights movement that was going on simultaneously with the antiwar effort. After wasting a great deal of time, I finally came to the realization that I had a very small story of a nineteen-year-old woman’s personal journey against a very big historic backdrop, and that allowed me to jettison the parts that weren’t about that journey.

CR: You mention Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried in a number of interviews, and it is a go-to book for me when I teach. In what ways did The Things They Carried  inform The Fourteenth of September?

inform The Fourteenth of September?

RD: It was kind of my bible. O’Brien’s novel takes place about four years before The Fourteenth of September. By the time of my novel, the lottery had just been announced, and the terror had amped up to unbelievable levels, particularly on a campus which had the largest concentration of draft-age men with no real outside or parental influences. We were all simply scared to death, hearing stories about the ridiculously short life expectancy of a soldier under fire. The question of the day was, if I get a low number, do I go to Vietnam to fight in a war that I don’t believe in and that, by 1969, was just a body count, or go to Canada, which was another kind of death—you’d be alive but cut off from everything?

In the “Up a Rainy River” chapter of The Things They Carried, O’Brien depicts a character facing just that dilemma in all its pain and nuance. Reading it gave me a focus. I’d always thought of my story as the female equivalent of the decision to go to Canada, but I didn’t know how to pull that off. Once I read O’Brien’s book, I imagined what it would be if the character in than canoe, crossing the river to Canada, had been a woman instead of a man. In my story, what I’m trying to depict is a dilemma for a woman that is as close as possible to the emotional conflict of a man in that situation. Everything except Judy’s life is on the line. Her character is at stake—the person she has to live with the rest of her life. Judy’s coming of conscience became a metaphor for what the whole country—and everyone in it, male or female—had to face about who we really were.

CR: Throughout the novel, you play with the idea of the irritating convention of male importance over all else. The women’s lives and hopes and dreams are very much belittled, if not outright ignored. That’s how I remember my entire childhood in the late ’60s and ’70s: men’s feelings took precedence. But the young women in your book are pushing back against this norm, trying to give feminism some space. They’re fighting for equality in the midst of all of this turmoil.

I admired the way you never dropped that tension, how it seemed so intricate and tightly woven into the narrative. In what way(s) could the #METOO movement support your characters (or not)?

RD: Yes, these were the early days of feminism, and many of those passages were baffling to younger people in workshop. But to understand the times is to understand that push-pull between the morals we were raised with and the aspirations we were headed for. And just how unbelievably hard it was to be heard as a woman back in the antiwar days. We couldn’t just roll up our sleeves and cut to the chase. We had to fight the war, while justifying our standing to do so. We had to simultaneously maneuver the sexism of the times, as well as deal with our own rapidly changing attitudes about ourselves as women and feminists. Our role models were generally either desirable but not really in charge, like Vida, or abrasive, like Lori.

Meanwhile, as you worked hard to earn your radical “stripes,” guys would undermine you mercilessly, making fun of your attempts at this new radical-speak language and zeal for a cause they felt only they could understand. You’d get shot down again and again, inadvertently offering yourself up as a target as you tried to grow into a stronger, more feminist version of yourself. It was brutal, and not everyone was willing to go through it. At that age our egos were tender, and many of us wanted boys to like us. And there were many women in the movement who were there because of their boyfriends, and many guys in it after girls they hoped would look like Jane Fonda.

At that time, #METOO would have been laughed off as a concept. If men had understood that it was inappropriate to ridicule women—even while teasing (which is how teenage boys often interact with girls)—more female voices would have been heard, more ideas shared (instead of whispered into guys’ ears to emerge as their own), and, above all, many of those young women would have grown into their confidence sooner. Judy’s journey was also one of leadership, first inadvertently, then out of necessity. Think of how much easier it could have been. How different her ultimate decision may have been.

CR: The difference between an X and a Y chromosome was the difference between not going to war and going to war. At one point, there is a conversation about how the boys were moping around because a strike didn’t have the outcome they’d expected.

You know who they remind me of?” Marsha said later, as she pulled the cellophane off her last pack of cigarettes. “The football team after a game they just lost.

And I kept having to remind myself that these are all just kids. They’re all seventeen, eighteen, nineteen years old. That’s how kids act: the guys’ feelings are always expected to be more important than the women’s feelings. But in this case, that annoying patriarchal artifact has more teeth to it . . . the guys keep reminding the young women that they have more to lose, more at stake. The women push against this the best they can, but the fact of the matter was: the men did have more at stake.

How did that tension develop in the narrative? Did you know that, going into the writing of the novel? Or did it really develop organically?

RD: The fact that these are essentially teenagers facing a life and death situation, way beyond their maturity and coping capabilities, is a huge theme of the novel. David’s efforts to lead the campus antiwar movement, for example, are accomplished with the finesse of trying to be Big Man on Campus, and his attitude towards “girls” is no more refined. And feminism is still pretty young at this point.

Dealing with trying to “equalize” the stakes for both men and women in war has been one of the most difficult aspects of writing the novel, as well as subsequently describing the viability of its central conflict. I’ve had workshop participants and early readers tell me that Judy was being “selfish” to think of herself at a time like that, that the book will insult “real” veterans.

The prospect of death will always weigh heavier in any head-on balancing, but it is not the only measure. In terms of the larger theme of women in war throughout history, can we say that the experience of men and women in war is better or worse? Is it not, instead, equally devastating but different? Can grief and death be equal? Can courage or cowardice only be on the front—only direct, not indirect? Can we admit that various experiences of war can be equally tragic—and transformative, positively or negatively? Can we respect that war is terrible for everyone, and “degree” is not the issue? Can we admit that we all have stakes in both the experience and the outcome?

Maybe I pulled it off, and maybe not. But this argument is why we’ve only scratched the surface of the subject of women in war.

CR: Your characters are constantly having to prove their commitment to the antiwar movement—to each other and to themselves. You write:

“So you became a radical because of him?” Marsha asked. “Bet he was cute.”

“You really think I’d do it just for a guy?” Vida snapped. “Hell, I was adding up body counts back in high school.”

This sort of “one-upping” seemed so natural to this age group, to movements, to people really committed to something. It also proved critical to the overall plot structure. Can you talk about that “one-upsmanship” without giving away the plot?

RD: You’re right, in that teenagers are competitive and self-righteous, particularly so as they are breaking away and thrashing around trying to make decisions about their own philosophies and points of view. They are vested in their own feelings and don’t realize that they may still be in formation. During the time of the novel, we were smack in the middle of a huge generation gap, a war, and all the societal upheaval of what the year 1968 had brought. The characters in the novel are also hearing about new ways of looking at life through their studies and from their teachers, and, with still embryonic abilities to learn and assimilate new information, they pick sides and test each other. It’s part of the definition of being a teenager and ebbs and flows in its “shrillness,” depending upon the times.

I was recently in a program given by Medill about the impact of 1968 on Chicago. The audience was older, and a young woman presenter essentially attacked us for not addressing current social issues in ways she felt were completely obvious and easy. Her arguments were visceral and certainly far from cohesive. I realized that this is how we probably sounded to our parents and others back in the years depicted in my novel.

Sometimes this one-upsmanship can lead to actions that, as the characters in The Fourteenth of September experience, are far from the original goal.

CR: The times also tore families and friends apart . . . or at least cut deep divides. At one point in the story, Judy and her roommate and friend from home are discussing Judy’s newfound activism.

“I’ve had it,” Maggie said, angling her head toward the wall so she didn’t have to look at her. “It’s one thing for you to be hanging with all your hippie friends instead of me, and I have to listen to all this peace/love stuff, but now you’re crowding me. I am from a marine family, you know? Like you are from an army one, remember? Jesus, Judy, Rick is over there.”

Did that same schism pull apart your own family and friends?

RD: Oh, absolutely. I had sent gut-wrenching letters that attempted to communicate my feelings, which, contrary to intention, hurt my mother’s. My father thought I must have been drinking. I took those responses as an excuse to distance myself—after all, I tried, and they blew it!

When I went home to visit, it was tense. First off, I arrived in clothes my mother couldn’t believe I thought “did anything for me.” I was playing strange music and lying on the couch just “listening” to it and smoking—a new, filthy behavior. I was angry about my parents’ rejection of what I felt were my attempts to explain where my head was at. I took to doing things to shock my mother, just to see if I could change the set jaw of disapproval she’d adopted. I told her I’d tripped on acid. I played the Hair album relentlessly on my record player, replaying the song “Sodomy” when she was in the room. My younger siblings were angry with me because when I came home my parents got mad.

My friends from high school didn’t know what to make of me either. They didn’t want to hear about the war. I tried to distance myself from the preppy girl I’d been who hadn’t been aware of world events. I kept it up. I was maid of honor in my previous best-friend’s wedding and wore my hair bushed out and wild, like the hippie I’d become, and complained about the war to the point where I alienated the best man, who was a vet.

I have to give my friend credit. When her new husband was drafted and ended up in Vietnam, she complained to him about all my antiwar activities. He wrote back to her to “tell Rita to keep it up,” and she told me. Had I been in her shoes, I’m not sure I would have.

It was a very hard time. I resented having to explain myself to old friends and family, and they resented my attitude. I stopped going home, except for short stretches around the holidays. I went to summer school every year so I could stay on campus. I felt like an alien on my own planet, and I’m sure they all felt I was eating green cheese.

I was obviously wrestling with something I had yet to fully understand—about who I was and how closely that was or wasn’t tied to the country I was in. Those from my family and high school life didn’t understand why I was putting myself through it. And yet, look what I’d seen happen on my own campus, to my friends . . . I was typical of my times. You either were apathetic and stuck your head in the sand, or you were raging and off-putting. As my mother said much later, “You were hard to like in those years.”

CR: Why do you think that the dilemmas faced by your characters are important to understand in this particular moment in time?

RD: The parallels to today are uncanny. When Ken Burns introduced his documentary The Vietnam War at a venue in Chicago, he painted a picture—a president no one likes or trusts, an intractable and strident Congress shouting insults from different sides, a polarized, angry country. Then he said he was talking about 1968, not today, and the audience laughed uncomfortably.

It’s very frustrating. We were the generation who was going to change the world, and now we find ourselves mired in what I call the hamster wheel of history. And yet, I’m encouraged by the Never Again movement, for example, which shares a lot of “triggers” with the previous antiwar movement, in terms of young people with their lives on the line without the power of a vote, who’ve been let down by the government and others who haven’t been courageous enough to secure the political action that would protect them.

The tag line of The Fourteenth of September is A Coming of Conscience. That defines Judy’s journey in the book—where integrity trumps consequences. But it also resonates as a call to action even today.

Now more than ever since the Vietnam era, we need a collective Coming of Conscience moment to decide the character of the country and ourselves. In that spirit, I am initiating a social-giving campaign as part of the launch of The Fourteenth of September to encourage young people to engage in meaningful activism and bold personal responsibility as they continue their education.

The initial iteration of this program will fund a Coming of Conscience Scholarship for a student at Northern Illinois University, the real-life inspiration for the fictional university in The Fourteenth of September. The up-to $10,000 scholarship will be awarded to a student who best demonstrates their understanding of what a Coming of Conscience means and their plan for how they will use whatever degree they choose to help change the world in whatever way their beliefs guide them.

Rita Dragonette is a former award-winning public relations executive turned author. Her debut novel, The Fourteenth of September, is a woman’s story of Vietnam which will be published by She Writes Press on September 18 and has already been designated a finalist in two 2018 American Fiction Awards by American Book Fest, and received an honorable mention in the Hollywood Book Festival. She is currently working on two other novels and a memoir in essays, all of which are based upon her interest in the impact of war on and through women, as well as on her transformative generation. She also regularly hosts literary salons to introduce new works to avid readers. www.ritadragonette.com.

Pick up a copy of The Fourteenth of September at your favorite indie bookstore or HERE.

Christine Maul Rice’s award-winning novel, Swarm Theory, was called “a gripping work of Midwest Gothic” by Michigan Public Radio and earned an Independent Publisher Book Award, a National Indie Excellence Award, a Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year award (finalist), and was included in PANK’s Best Books of 2016 and Powell’s Books Midyear Roundup: The Best Books of 2016 So Far. In 2019, Christine was included in New City’s Lit 50: Who Really Books in Chicago and named One of 30 Writers to Watch by Chicago’s Guild Complex. Most recently, her short stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Allium, 2020: The Year of the Asterisk*, Make Literary Magazine, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Millions, Roanoke Review, The Literary Review, among others. Christine is the founder and editor of the literary nonprofit Hypertext Magazine & Studio and is an Assistant Professor of English at Valparaiso University.