By Rachel Swearingen

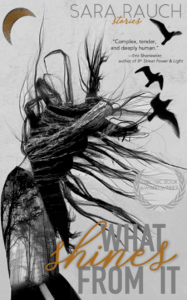

Sara Rauch’s debut short story collection, What Shines From It, released this March by Alternating Current Press, is so exquisitely spare and deceptively quiet that its power accumulates as you read. Many of the characters wound or are wounded. There are falls and accidents and surgeries, but the narrators of these eleven stories rarely fixate on their injuries. “We’ll find a way to live with this,” a character in “Kintsukoroi” says. “We’ll scar up.” The collection is littered with beautiful survivors: the “jagged tip” of Manhattan seen from a ferry years after 9/11, a feral kitten emerging from behind a dumpster, a tomato that looks like a “barbed heart.”

Sara and I talked over email about how What Shines From It came to be, about patterns of imagery, serendipitous reading, the influence of poetry, the beauty of small plots and perfect landings, as well as the difficulty of writing in the aftermath of 9/11 and the current Covid-19 pandemic. –Rachel Swearingen

Rachel Swearingen: Now that I have finished What Shines From It, your title seems even more appropriate to me. It works on so many levels. Days after reading your last sentence, I’m thinking about how some books continue to glow after they are set aside, how some leave a residue on the reader that lasts. Your title (and your epigraph) comes from Anne Carson’s The Beauty of the Husband. How did you come across her book, and what made you finally choose this phrase as your title?

Sara Rauch: I discovered Anne Carson as an undergrad, on the recommendation of a beloved professor; when The Beauty of the Husband came out (in 2002, it must have been), she put the book on my reading list, and I fell in love with it. I’ve read a lot of Carson’s work, and I think she’s brilliant, but what has stuck with me over the years about The Beauty of the Husband is how Carson turns the mundane dissolution of a marriage into high art. So much of my career as a writer has been aimed at this endeavor: elevating the everyday into art. The phrase what shines from it must have been obliquely influencing me all this time—two of the stories in the collection originally bore the title (“Slice” and “Kintsukuroi”) and it was the collection’s working title from the moment I perceived that I had a book on my hands. Even once all eleven stories came together, that phrase (and the idea that pain and beauty are so intimately connected that they cannot be pulled apart) persisted as an overarching idea, and I wanted to honor its origin.

RS: Wounds and injuries appear throughout these stories, as does the subject of healing. I find it remarkable that these moments never feel repetitive, but rather purposeful. Your characters and situations are different enough that their juxtaposition stitches a larger narrative into the book, making the stories feel both separate and cohesive. When did you realize that this was a theme in the book as a whole? What was your revision process like?

SR: Sometimes I joke that I feel bad for my characters because I know that at some point in a story they’re going to bleed! Joking aside, oftentimes I will get obsessed with a certain thing and not really realize or understand why until much later, and something like that happened when I wrote the stories in What Shines from It. Thinking on all of this now, I can recognize that while I wrote these stories I was trying to make sense of how a person heals from pain because I myself needed to know how. The stories weren’t originally written with any intention to be a collection—I was just writing them, moving from idea to character to plot—but then I wrote “Kintsukuroi” (the last story to be completed) and I realized I had something altogether cohesive. Once that clicked into place for me, I went through a few rounds of revisions with the stories ordered side by side so that I could make sure they really belonged together, and that was actually pretty fun, because it helped me gain a new perspective on what I was aiming to capture.

RS: Another thing I admire about What Shines From It are the details about physical work and domestic labor. Characters design and hand-stitch dresses, throw pots, attend conferences. They chop wood, bathe children, deal with mice and bats and stray kittens. They cook and caretake. How much do you draw from real experience, and how much do you research? Do you find particular types of situations or characters recur for you?

SR: I love this question! I grew up in a family of hardworking, hands-on, do-it-yourselfers and though I took a decidedly different course by pursuing literature and a life of the mind, my upbringing still influences so much of how I inhabit the world. Being alive is such a tactile experience, rich in physical stimulus, an onslaught of sensation. When I write, I like to give my characters something to do—something that engages them in the world—because it’s very revealing; how a person interacts with the outer world reveals something of their inner self.

Some of the things you mention—cooking, sewing, chopping wood, dealing with mice and stray kittens—I have experience with and was able to take that (sometimes limited) knowledge and delve deeply into it for the story at hand. After reading “Slice,” my best friend, who is a talented seamstress, said to me, “I had no idea you knew so much about sewing!” and that felt like such a huge compliment. I mean, I know how to stitch a basic pattern, and that was a starting point for the story, but I did a lot of research to get the more complicated details right. Most of the stories are like that—starting with an inkling of knowledge and then pushing out from there. In general, I find I am drawn to writing about working artists or craftspeople who are struggling with their desires—for connection, for success, for understanding their place in the grand scheme of things.

RS: Each of your story titles is just one word, which lends a sense of unity and musicality to the collection as a whole. Can you tell us a bit about this stylistic decision?

SR: As with many things that I only vaguely understand about my writing process and preferences, I blame this choice on poetry! I trained as a poet prior to switching over the fiction, and have carried with me a minor obsession with the potency of a single word. Two-thirds of the stories already had single world titles when I submitted the manuscript, and during the final set of edits, Leah [Angstman, Alternating Current Press’s editor] and I made the decision to make all the titles one word. Each title has multiple meanings for its story, and I like this idea of allowing the reader to find however many meanings they want to within the narrative.

RS: Can you tell us about an unexpected discovery while writing What Shines From It?

SR: Ooh, yes! I laugh to admit this now, but in writing these stories I discovered I hadn’t been giving plot its proper due. My fiction remains fairly character driven, but by some combination of guidance and epiphany, I came to terms with the fact that I wanted to write stories in which things happen, in which something is at stake, in which characters move toward what they want, not only mentally and emotionally, but physically. I used to have this idea that plot needed to be BIG, but plots are also small, the stuff of everyday, and once that clicked, the whole concept of “story” changed for me.

RS: Your endings are often beautifully understated and yet loaded. Again, the image of a not quite healed wound comes to mind. Can you describe your process of arriving at an ending? How do you know when a story is finished?

SR: An image that I keep in mind when I’m working on an ending is that of a plane descending after a flight—you start to feel the change in air pressure and the anticipation of arrival, and then even though you can see the buildings growing larger and the runway stretching ahead, that moment when the wheels touch the tarmac reverberates through your body. I think a good ending feels like that: you know it’s coming and still it jolts you. And, in a way, you’ve only just arrived, so you know there’s more to the story, but that’s all still in the future and you’re just in the moment of taxiing toward it. That being said, I’m not sure I really ever know how I arrive at an ending! It’s a bit obscured, even to me, but I guess part of it is fully inhabiting the story as a writer so that I know where to “land” it. The rest remains a sort of alchemy.

RS: Your dialogue is so fantastic that I believed all of your characters and could hear their individual voices. This was especially true of the story “Answer,” where two unlikely strangers meet and spend the day together. I’m curious how that story came to you and evolved. Do you tend to write by ear? Or are your stories triggered in other ways?

SR: One of my favorite pastimes is eavesdropping on strangers in public places! It is somewhat embarrassing to admit, but I am often listening in on what other people are saying to each other, and also what they are not saying, and I’ve discovered that dialogue in fiction has to work on both of those levels to do its job. So I guess I do write by ear, and by intuition (to “hear” the unsaid). “Answer” in particular came to me out of a confluence of elements all circling around the idea of freedom—what that concept means to humans, what freedom means to wild animals living within urbanized spaces, what freedom means to our collective culture and the collective unconscious—but I wanted to bring those big ideas down to tangible scenes, and it made sense to me that two complete strangers would be more willing to reveal their deepest and rawest selves to each other, because what, really, do they have to lose?

RS: This might be an unfair question, but which story in the collection is your favorite? Which was your most difficult to write? Why?

SR: Not unfair at all! I mean, I do love all of the stories for different reasons, but my favorites are probably “Kintsukuroi” and “Beholden.” Both are as close to autobiography as I feel comfortable coming as a fiction writer, and though they were emotionally wrenching to write, both came out fairly whole, which always feels like some kind of grace. The hardest story to get right was “Free,” which went through close to 100 drafts before reaching its final form. Thinking back on it now, I’m amazed I stuck with it! But there was something about the two girls’ friendship, and the unlikely scenario they find themselves in, that kept haunting me.

RS: Several of the stories deal with the aftermath of unforeseen tragedies, in particular, New York after 9/11. “Beholden,” your final story, captures the inexplicable grief and confusion New Yorkers felt in the city in more immediate aftermath. The story is also your most fragmented and lyrical. When in the process of writing the collection did you finish this story. Could you tell us more about its development?

SR: “Beholden” was one of the last stories I wrote (I think only “Kintsukuroi” came after it)—though it’s written in a style I’ve long been trying to perfect. That lyric fragmentation seemed to allow the story the strangeness it needed to have to pull off its intention. As I mentioned above, the story is essentially autofiction (ghosts and all) and though on some level that kind of writing is freeing, in that I didn’t have to worry at all about inventing a plot or characters, I also found it somewhat tricky to navigate a world I once knew so intimately. I had to weigh each detail carefully, to decide what truthfully strengthened the narrative and what needed to be created to elevate it to story. It’s a harder task than it first appears!

RS: Speaking of calamity, What Shines From It was released on March 3rd, towards the beginning of an international pandemic. What has this been like for you? Have you been able to celebrate? If you’ve been able to continue your writing practice, what are you working on or thinking about now?

SR: It’s been strange! There’s just so much that’s shifting in the world, so much uncertainty and fear and loss, and it can be hard to know where to stand, as a person and as an artist. I’m blessed/cursed to be an incredibly sensitive person, and the state of the world pretty much always causes me to feel a blend of terror and hope, and now with this pandemic that tendency is very heightened. But I try to keep moving forward with an open heart and to do my best, which I’ve discovered is probably the only thing I have any control over.

Unfortunately I didn’t get to attend AWP in San Antonio [where I had a release reading and book signing scheduled] because an awful sinus infection struck me down at the exact wrong moment, but I did have a reading set up at Pinch [the shop where I worked while I wrote the book] in Northampton, MA, in early March and we went through with it. It was the same day that Trump declared a state of emergency, so it was sparsely attended, but still gratifying to see old friends and share a little bit of the book in a real-world setting.

I have been able to continue writing through all of this—I don’t know if it’s pure stubbornness, or fear that if I stop I won’t start again, or just that as a mom to two young kids I’ve had to constantly figure out a way to write through challenging times, but it does feel like a gift that I keep showing up, and definitely not one I take for granted. It might be, too, that I’m in the throes of revising what I hope will be my first published novel and it’s got me under its spell!

Sara Rauch is the author of What Shines from It: Stories, winner of the Electric Book Award. Her writing has appeared in Paper Darts, Split Lip, Hobart, apt, So to Speak, and she’s covered books and authors for Lambda Literary, Bitch Media, Bustle, Curve Magazine, Colorado Review, The Rumpus, and more. She lives with her family in Massachusetts.

Rachel Swearingen is the author of How to Walk on Water and Other Stories, winner of the 2018 New American Press Fiction Prize (forthcoming September 2020). Her stories and essays have appeared in VICE, The Missouri Review, Kenyon Review, Off Assignment, Agni, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago.