By Christine Rice

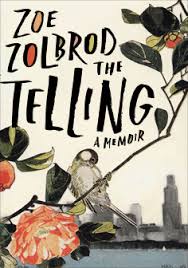

Reading Zoe Zolbrod’s The Telling felt like exhaling after holding my breath for a very long time.

I suspect that many readers will identify with the child Zoe was–one unable to rightly identify the sexual abuse she quietly endured at a young age, to put words to it. It’s nearly impossible not to identify with Zolbrod as she unflinchingly examines what her older cousin did to her. It’s a scientific approach, for sure: observation, formulation, examination, result. The journey takes us from the messiness of childhood and her young adult years, into marriage and parenting, and after extensive research, leaves the reader with a sense of how those events influenced (and continue to influence) the person–daughter, friend, spouse, parent, citizen, writer–Zolbrod has become.

Zolbrod opens the book with an epigraph from Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Living Living To Tell The Tale.

What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.

That quote suggests a disconnect between memory and reality–but then again–maybe not. That said, I trust Zolbrod’s account, her memory of events. Her memories feel reliable, even when she doubted herself. She angles to understand why the young version of herself didn’t tell (until years later when the now adult cousin, who she calls Toshi, is charged with molesting a girl) and, by the end, you have a deeper understanding of why abused children keep their mouths shut.

And that’s what really struck me. There’s a deep respect for childhood experiences throughout the book–for herself, for Toshi, and for her own children. And while Zolbrod clearly defines Toshi’s reprehensible behavior and never excuses it, she never fully demonizes him either.

Instead, she makes him flesh and blood. She writes:

And certainly my heart goes out to teenaged Toshi, banished from his home. Seen as a burden, the bearing of which had to be pleaded and compensated for. There are few takers for stray teenagers, those monsters of mood, oil, limbs, sex, and stink. What a time to be thrust out to stalk the earth. It’s even more painful to consider the plight of young Toshi and his sister. For the two young children taken from their mother, gone. To not be mother-loved.

Zolbrod’s debut novel, Currency, received an honorable mention by Friends of American Writers. Her work has appeared in Salon, The Nervous Breakdown, The Weeklings, and The Rumpus, where she serves as Sunday co-editor.

We caught up to talk The Telling, colicky babies, what we’re dissuaded from writing, the tension between parenting and writing, among a few other topics.

Christine Rice: At times in your life your anger nearly tipped you but the writing always felt clearheaded and truthful. I’m wondering how you walked that tightrope (during the writing) between anger and sympathy, how you strove to get to the truth as opposed to making the truth fit the story?

Zoe Zolbrod: I’m glad to hear you say you sensed I was striving to get to the truth as opposed to making the truth fit the story, because that was my motivation. The stories I’d absorbed about childhood sexual abuse from the dominant cultural narrative weren’t a good fit for me, and I had trouble making sense of my own experience. I came to this project with much more confusion—and just plain curiosity—than anger. In fact, one of the things I wanted to explore was why I didn’t feel angrier, why it took me so many years to. But once I started poking around inside myself—and especially when I thought about the impact on other children—I did get angry. Sometimes that came as a relief—the purity of it, the simplicity. But it was also scary. It’s my natural inclination to pull back and analyze.

CR: Throughout the book, you turn to your journals to back up memory–to reference time and event and place and emotion. How important were your journals in writing The Telling? How did they inform the writing? Did they ever throw you off? Surprise you? How have your journals functioned in your journey as a writer overall?

ZZ: I kept a journal from my late teens through the early years of parenting, and man was I glad about that when it came time to write this book. I was especially grateful for the chunk that I had typewritten on my first computer, a Mac SE, and printed out, because reading my messy handwriting in faded ink on disintegrating spiral bound notebooks got old. But I pored over every word, and I reabsorbed everything in there, to the point that it’s hard for me to remember now what surprised me, or ran counter to my memories. It did occur to me as I was reading that although we think of journals as primary sources, as a truth more reliable than fickle memory, they are themselves recreations, where we construct personas and tell stories. Sometimes I could sense my journal-writing self performing for herself, if that makes sense, or creating herself as a character. With hindsight, I can see I was honing my writing chops. I kept journals for years before I started writing fiction or essays.

ZZ: I kept a journal from my late teens through the early years of parenting, and man was I glad about that when it came time to write this book. I was especially grateful for the chunk that I had typewritten on my first computer, a Mac SE, and printed out, because reading my messy handwriting in faded ink on disintegrating spiral bound notebooks got old. But I pored over every word, and I reabsorbed everything in there, to the point that it’s hard for me to remember now what surprised me, or ran counter to my memories. It did occur to me as I was reading that although we think of journals as primary sources, as a truth more reliable than fickle memory, they are themselves recreations, where we construct personas and tell stories. Sometimes I could sense my journal-writing self performing for herself, if that makes sense, or creating herself as a character. With hindsight, I can see I was honing my writing chops. I kept journals for years before I started writing fiction or essays.

CR: You structured The Telling in three parts and it moved elegantly through time very much like a novel. You also developed a number of characters throughout the narrative so that, by the end, the reader gets a clear emotional view of each one. Your first book, Currency, is a novel. In what ways did the experience of writing a novel influence the structure and writing of The Telling?

ZZ: You know how some writers are like: “First, I create an outline.” And others are more: “I start with an image and I have no idea where I’m going to end up.” For both the novel and the memoir, I’ve been somewhere in between, outlining as I go, usually about six or eight chapters ahead from what I’m currently writing. Both times, I did better when I had a sense of what I was writing toward but when I still left room for discovery. The novel is told in chapters that alternate points of view, so alternating between time periods in the memoir was familiar to me. And maybe writing a novel—which is all about empathizing with various characters in a scenario—helped me empathize with the people who are part of my own story.

CR: As a reader and writer, I appreciated the balance of fierceness and vulnerability that coexisted on the page–pushing yourself through the telling, forcing yourself to be as clear and honest as possible and, because of that, leading the reader to certain truths. How long did it take to write The Telling?

ZZ: I conceived of the book in 2010, but I was slow to get started. I had a lot to process emotionally and psychologically. I read all my old journals, I did a fair amount of research, but when I’d go to actually write, my hands would often remain frozen over the keyboard. It wasn’t until about 2012 that I really got cooking, and then the writing went relatively quickly, considering I have a full time job and two kids. I had a full, once-revised draft by the end of 2013 and signed with my agent in early 2014.

CR: Like your son, my first daughter was colicky, cried pretty much all day, and I distinctly remember my frustration with the parenting books of the time. I would try to find out how long this stage would last, try to find someone whose experience matched mine. But I couldn’t, of course, the baby books were useless. There were no memoirs or personal narratives about how to deal with colic. There were no touchstones.

Same with the abuse. There were clinical books but nothing about how the child might react or feel. There was no identification or validation of feelings to be found (or few…and difficult to find).

And that’s because, I suspect, like many women’s issues, we were often dissuaded from writing about those issues. After all, would Hemingway have written about this? Tolstoy? So as women writers, we were made to feel (by the industry and other writers…as you point out at the end of the book where a male writer friend dismisses your subject matter and goes on to say that he has been writing a book about his childhood baseball card collection) that our journeys were insignificant, unimportant. Or already done.

So I loved the fierceness with which you pursued the subject and those more vulnerable moments when you doubted yourself. But it’s all in the approach, isn’t it?

ZZ: Those months with a super colicky baby are something, right? Hands down the most intense period of my life—more than hitchhiking cross-country, more than being deliriously sick in Hanoi with my visa running out. But yes, there’s the sense that these stories are overdone, or that they’re small stories—I definitely internalized that. And there’s the industry inclination to package and market any book about a woman’s experience in a certain way. I received a few rejections where the editors praised the writing but said that the book didn’t fit in the recovery genre and they didn’t know how else they’d market it.

Did you read the essay “The Reluctant Memoirist” by Suki Kim that was making the rounds?

CR: No…but it is now on my list.

ZZ: I was fascinated by it. She went undercover in North Korea and did some deep investigative work about conditions there, but then, against her will, her publisher packaged her book as a memoir—a story about her feelings, rather than a source of knowledge about the subject she’s an expert in—and she was lambasted for her methods. Her book was NOT a memoir and I understand her anger, but I also notice the shame she associates with the genre, that she sees herself as reduced to it in the writing of the essay.

Here’s a quote:

I recognize the irony here: Sifting through my memories, recalling again and again what happened has turned me, in this essay, into a memoirist. My book is about North Korea, but this essay is about me, and for me, there is something deeply humiliating about being so self-obsessed. Here I am telling my story to you, the reader, essentially to beg for acknowledgment: I am an investigative journalist, please take me seriously.

I’d like to push against the dichotomy—and Kim didn’t invent it, nor do I want to push against her—that says a book about our feelings can’t also contain knowledge, as well as against the dictum that writing about the self is the same as self-obsession. For me, researching child sexual abuse and pedophilia was as important as exploring my own experience—the two entwine, actually; they inform each other—and presenting the information I learned to readers was part of my project. I’m not entirely comfortable calling myself an expert on the topic, but you know what? Maybe the combination of informed layperson’s knowledge and deep thought on the issue and personal experience makes me something that’s in some cases better. Maybe a book written by such a person is what we both would have liked to find when our arms were quaking from holding a screaming baby all day and night. I probably could have used a book like that even as a teenager when I was starting to realize the nature of what my cousin had done to me.

CR: Yes. Knowledge and feelings exist beautifully and harmoniously in The Telling.

There’s always a relief when a story or book is finally out in the world but I’m curious if, with this, because of the really difficult memories and material, you felt extra relief? Or anxiety? Or a mix of both? Or neither?

ZZ: I felt extra anxiety through the last round of editing and initial publication, and now I’m feeling extra relief. My parents have read it; some relatives have read it; so many people from various walks of my life have read it and been supportive; the reviews have been good. I feel buttressed by all this and like I can take some arrows now without going down. And it’s been amazingly freeing to stand openly beside all this stuff that I felt secretive about for so very long.

Every time I told someone I’d been sexually abused, I questioned why I did it, and many times when I thought about what my cousin had done to me, I wondered why I didn’t tell anyone when the molestation was occurring. This second-guessing is common among both people who have been sexually abused and those who eventually find out about it, and the timing of telling or not telling is the cause of a lot of guilt and discomfort as well as some level of disbelief. As much as I haven’t wanted to view my life as a single-issue case study, it’s helped me to learn that there are common reasons why children tend to keep quiet about abuse, and that–although prompt disclosure can aid in kids getting the right kind of help–some of these reasons make a grim kind of sense.

CR: Wonderfully, The Telling is as much the story of what happened in the past as it is a researched path for the abused child/adult to follow, to come to some kind of peace with the past. Was that your intention all along or did you come to realize this further into the writing?

ZZ: I came to that further into the writing, as a result of my research. The more I learned, the more I realized that there are so many myths still circulating about all aspects of child sexual abuse, and the more convinced I became that information needed to be shared—for the sake of those who have been abused and those who are close to them, and also for parents of young children.

CR: In the chapter “What Should You Tell,” you recall a PTA meeting about substance abuse where the presenter, basically, encouraged ‘zero tolerance’ when it came to drugs and drinking.

If the cold, prim presenter was getting to me–and she was, well beyond the scope of the topic–it was because in its broad sense this question about the motivation for telling unsavory truth was one I was sitting with every day as I mulled over writing this book, and she was offering an institutional answer to it: yes, telling the truth was selfish when it comes to children, and if I wanted the best for mine, I might have to give it up. The conclusion I was jumping to was that she–”they,” “everyone,” even my husband at times, though he was reluctant to show it–thought that shutting up about the messy stuff was what a responsible, right-thinking person, or parent at least, does, because responsible,responsible, right-thinking, never-in-distress or too-far-off-the-path people are what we’re looking to turn out.

And, again, this whole parenting thing is so nuanced and subtle. It’s also so individual. I really appreciated those end chapters where you brought in your parenting experience. It made a wonderful sense to me as a reader and also brought the sense of wholeness full circle. I’m curious if you knew that you would write about your own family/children in this memoir or if the narrative demanded it?

ZZ: I knew from the beginning that my parenting was part of the story. The book is structured around my changing interpretation of the events of my early childhood, and nothing shifted them—and continues to—more than raising my children. For one thing, there’s the sense of responsibility towards the younger generation that dropped on my head like a grand piano once I had my firstborn. Almost simultaneously, I learned that the guy who abused me had recently been caught doing the same thing to another little girl the same age I had been, and so the two things seemed bound up: the responsibilities of a parent, and figuring out why I had reacted to my abuse the way I did. For another thing, I quickly realized that my work on the book was affecting my parenting, and vice versa. I wanted to capture that in the real-time strand. Also, I wanted to reflect on parenting itself, maybe in part to defend my own parents for any mistakes they might be accused of. Raising kids is hard. We want to both protect them and ready them for independence, and we need to live our lives, too. Most of us are doing the best we can.

CR: It struck me, throughout, how you emphasized your middle-class upbringing. It is important to the narrative, to your own story, but also it is important to point out that this kind of abuse happens everywhere, to all kinds of kids–wealthy, middle class, poor. And while you were often frustrated by and railed against middle-class sensibilities, you were/are proud of them. I found this tension compelling because I often write about the middle class. These values, in the end, are part and parcel of your character.

ZZ: I came to feel fortunate about the stability in my childhood and the values of my parents—their essential kindness and open-mindedness, their hard work, their love of books, their respectful rather than authoritarian parenting style. I don’t necessarily equate all those values with the middle class, exactly, but basic economic security is so important to a secure childhood, and not everyone I knew had that. Realizing how lucky I was made me loath to speak in any way that could be construed as whining about my childhood experiences. I wanted to acknowledge all the good but also move away from considering my own molestation as something that was “not that bad.” It’s always been a sticky wicket for me.

CR: There have been more and more interesting (some infuriating, some wonderful) essays about the tension that exists between parenting and writing. Without discounting the struggle, this book (and countless others…especially in the past few decades) are testaments to just how silly it is to suggest that a woman writer should only have one child, for example, or that we shouldn’t write at all.

You are incredibly loving and generous to your parents in The Telling–their hopes and dreams, their faults, their triumphs. Can you trace your ambition to write?

ZZ: My dad has published a number of books, most notably Dine Bahane, a translation of the Navajo creation story that’s been translated into German and French and that remains in print. He worked on it all through my childhood, and the racket of his manual typewriter clacking away in his basement study is the soundtrack of my youth. He had a couple sabbaticals in there, but he did most of the writing while teaching a heavy load at a liberal arts college and actively parenting me and my brother, so the example he provided was that it can be done. Before that—before I was born—he took time out from graduate school to write a novel inspired by his experience in the Korean War, called Battle Songs. He came close to getting it published in the 1960s, but the editor that acquired it left the publisher when they merged with another, if I’m recalling correctly, and it never came out. In the 2000s, he unpacked the manuscript and dusted it off and revised it and had it copyedited and published it himself. It’s really good! So the other example he provided is that you can keep believing in a project over the long haul, even when the gatekeepers aren’t paving your way. And he always encouraged me to find some work outside the home that would give me satisfaction, something that neither my grandmother or my mother were able to do, for various reasons including those of era and gender.

As for me, I wrote a novel and a couple plays as a kid, but it wasn’t until I was a few years out from undergraduate school that I made any adult attempt to write seriously. I did try to squelch the desire after my novel got rejected all over the place and I was working full time and parenting a toddler and just couldn’t figure it out. But as you see, I was drawn back to the attempt. I have another novel in the works, and I’m excited about that. Which isn’t to say it’s not really hard. My excitement is tempered by exhaustion, I’ll admit. My own self-serving opinion is that writing a book is difficult under any circumstance, but that the need to earn a living for those of us who do is as big a factor as parenting when it comes to obstacles to doing our best creative work. But they’re obstacles that can be overcome.

Christine Maul Rice’s award-winning novel, Swarm Theory, was called “a gripping work of Midwest Gothic” by Michigan Public Radio and earned an Independent Publisher Book Award, a National Indie Excellence Award, a Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year award (finalist), and was included in PANK’s Best Books of 2016 and Powell’s Books Midyear Roundup: The Best Books of 2016 So Far. In 2019, Christine was included in New City’s Lit 50: Who Really Books in Chicago and named One of 30 Writers to Watch by Chicago’s Guild Complex. Most recently, her short stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Allium, 2020: The Year of the Asterisk*, Make Literary Magazine, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Millions, Roanoke Review, The Literary Review, among others. Christine is the founder and editor of the literary nonprofit Hypertext Magazine & Studio and is an Assistant Professor of English at Valparaiso University.