By Jael Montellano

I imagine entering the 1933 Century of Progress Fair felt to Chicagoans of the day like it did when I, decades later, first ascended the Grand Staircase of the Art Institute of Chicago. Over the Frank Lloyd Wright Coonley window, the sun dialed chromatic angles on the marble floor, and as I restocked visitor guides and exhibition pamphlets, then an impressionable new employee, the majestic galleries bated my breath with their luminous possibility.

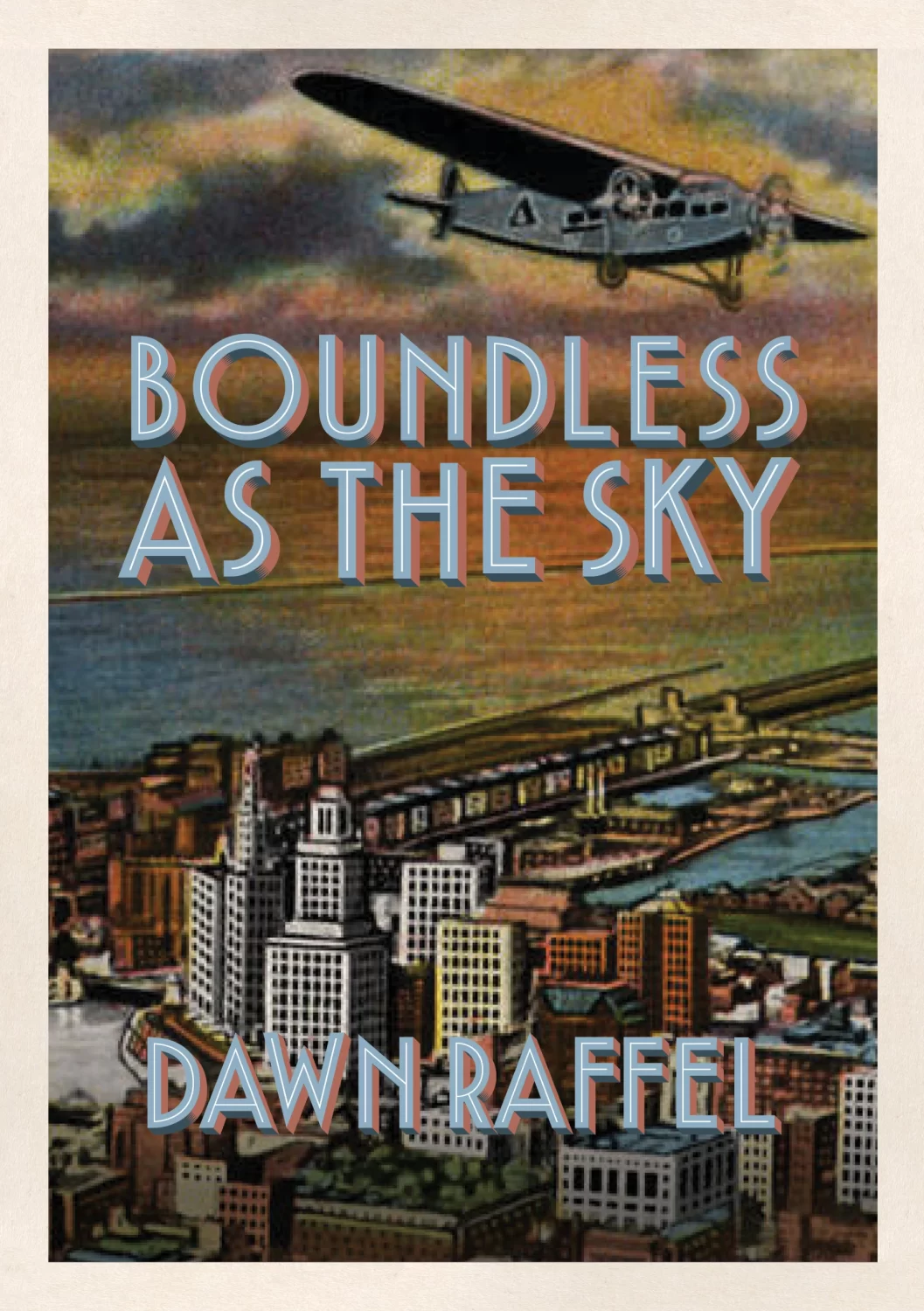

Dawn Raffel’s latest work, Boundless As the Sky, explores many visions of a city—cities past, cities imagined, but also Chicago on a day in 1933 where thousands of Chicagoans held their breath in anticipation of Italo Balbo’s 24-seaplane armada soaring over the fairgrounds. Trembling on the knife’s edge of fascism and war, plumbed in the miseries of the Great Depression, Chicagoans looked to the Century of Progress Fair as the harbinger of miracles to come.

Dawn Raffel and I conversed about her fascinating experimental novella below.

Your book is split into two parts; the first is an ode to Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, while the second follows a day of the World’s Fair of 1933. In a lecture Calvino gave to Columbia University writing graduates in 1983, he talked about the way he wrote Invisible Cities. He said he worked on it over years, “writing a piece every now and then, passing through a number of different phases” so that it became, of sorts, a “diary” recording his “moods and reflections.” What was your process in writing and shaping Boundless As the Sky, and what guidance did you take from Calvino? Is this process similar to yours?

The stories were written over a period of many years, between 2007 and 2021, so perhaps in some sense, it is a kind of diary, both of my inner life and of the world around me. The opening story, with the masked women, was written before COVID-19, and the masking that lightly pervades the book was already in place before we all covered our faces. Several of the cities were places that I visited over the years and then decontextualized. And a few, such as “The All-New Sanitary City” came as the lockdown was approaching.

With this book, as with every book I’ve written, I didn’t entirely know what I was writing toward until I’d gotten quite a bit down on paper. In other words, I don’t start with a big idea and then break it down; I start with small pieces—images, places, sometimes characters—and then work to find the connections and the larger picture. Even with The Strange Case of Dr. Couney (my most recent book before Boundless), which was historical narrative nonfiction under contract, I couldn’t have articulated the full resonance of the story until I was deep into the writing; I had to trust that it would emerge.

With Boundless, I certainly didn’t sit down and say, now I will write a response to Invisible Cities. I’d never have dared. Invisible Cities is a book that took up residence in my psyche a long time ago, and the more I wrote, the more I understood what I was responding to.

The “guidance” that I took from Calvino was to sharpen my sentences again and again. Something he said that has stayed with me and that I pass along to my students: “Everything can change, but not the language that we carry inside us, like a world more exclusive and final than one’s mother’s womb.” And yet it is a lifetime’s work to access that language and get it onto the page. I revised these stories repeatedly over the course of the years, and some are now quite different from the way they originally appeared in literary journals.

Lastly, I deliberately did not want to copy the structure of Invisible Cities, or attempt some kind of retelling. That seems like a fool’s errand. I wanted this book to be its own thing, while nodding with admiration toward Calvino.

Calvino said he believed he had written “the last love poem addressed to the city” because he felt it was becoming “increasingly difficult to live” in them due to the fragility of the environment and the overgrowth of megacities. This sounds eerily like the present day. We are seeing people priced out of city living or undergoing a deterioration in living conditions to remain within overcrowded spaces. Global warming looms and natural disasters are on the rise. What within Calvino’s work were you responding to with your real and invented cities? What within present-day life did you wish to reflect?

Natural and man-made disasters, in particular flooding, fire, and war, ripple throughout my book. Some of the stories are a reference to climate change; others reflect on the past or project the future. I’m trying to evoke the way a city’s history and the seeds of its future repose within the current city. In my lifetime alone, many cities have been renamed and in some cases now belong to a different country, which has also been renamed. Go further back, and you’ll find cities that are altogether defunct. Any city is a construct, with temporarily agreed-upon borders and names. And while you might, for instance, consider Chicago a visible city, Chicago of 1933 is an invisible city, yet still present.

As difficult as it is to live in a city, I suspect people will continue to love and live in them—at least I hope so. It seems to be in our nature to want to be together, no matter how messy it gets.

Centered within the book is your photo series titled “The Lost City.” It is mentioned, in the contents, that you lost most of the collection in a flood. What was the collection originally like? What had been your intent in its gathering, and how did this change after the flood? What directed you to include its remnants within this book?

When I first came to New York, I was living on an assistant editor’s salary (i.e. something close to nothing), but I bought a little Nikon camera and walked all over lower Manhattan with it. Having grown up in Wisconsin, I wandered around the city in a perpetual state of amazement. At the time, circa 1980, New York was dirty and dangerous, buzzing with nervy energy, and still cheap enough for the artists, eccentrics, and elderly immigrants to live in Greenwich Village. The city never slept, yet you could find unexpected pockets of quiet and stillness. I photographed in black-and-white Fuji film because it was cheaper than color.

For me, photography was less about documentation than it was a way of seeing more deeply through the act of composition—which, I suppose, is the same thing I try to do as a writer. I had never thought of these photos as a “collection.” At a certain point, I put them away, and I have no idea what happened to the camera. Early in 2012, it occurred to me that the city I had photographed in 1980 was lost. From over a hundred fading photos, I put together 13 to make a visual story for a pamphlet series published by Ravenna Press. If I had not taken those 13 out of storage in my basement, they would have been destroyed in Hurricane Sandy, along with the rest of the images, when five feet of water rushed into my basement. As Boundless began to take shape, I culled a smaller number of those surviving photos in order to create a story more proportionate to the collection and its themes. Perhaps it is fitting that most of the photos were destroyed in a flood.

Why was it important that the series of real and invented cities precede the second-act of Chicago’s “Century of Progress” World’s Fair? Why Chicago’s second world’s fair at all? What links did you discover juxtaposing these sections within your editing process?

In the “The Lost City,” there is an image of graffiti that reads: “Everything happens all over, all the time at once.” An unknown person wrote this on a wall in Soho long before there was a movie called “Everything Everywhere All At Once”—but of course, it wasn’t a new idea then, either. I happen to believe it’s true—things that occur in one place and time affect everything else, and any city we can imagine has roots in reality.

To my mind, the two parts of the book are in conversation with one another: the invisible and the visible, the grounded/subterranean and the airborne, the non-chronological and the hyper-chronological. In terms of technique, there are references to feathers and flight throughout the book, beginning with the opening “The Author.” And there are also definitions and questions of storytelling and authorship in each section.

As for my obsession with the world’s fair: In 1933, the bottom of the Depression and the year Hitler came to power, Chicago hosted The Century of Progress, predicated on the idea that technology would solve our problems. The official program guide stated: “Individuals, groups, entire races of man fall into step with the slow or swift movement of the march of science and industry,” a sentiment that was presented in an entirely positive light. Millions of people who really couldn’t “spare a dime,” somehow scraped together 25 cents for the price of admission. They came for a vision of hope, for a glimpse of a beautiful future that, as we know, never came to fruition. Yes, technology did change our lives, but not in the way people expected. Instead, technology serves as a tool to amplify our human impulses, both good and evil.

When you look at photos from the day of the arrival of Italo Balbo’s fascist seaplanes (“the roaring armada of goodwill”), you’ll see thousands of people waiting expectantly. From our perspective, we realize the young boys anticipating this show, enthralled by aviation, will be drafted to fight in WWII. And it’s hard not to wonder whether, in 1933, Hitler could have been stopped, if only we’d been looking at the right things in the right way.

The decisions people made in 1933 are with us now, even if the fair and the people who attended are gone. We feel the repercussions of their actions and inactions, just as they felt the repercussions of the past, in particular WWI. And it also begs the question: What are we failing to recognize and act upon now?

Invisible Cities is told in the frame narrative of Marco Polo speaking with Kublai Khan about his vast empire and its many cities; Boundless As the Sky does not have this frame narrative, however, both situate the reader as spectator; your collection has the reader experience the hours leading up to the arrival of Balbo’s seaplane armada through the eyes of various attendees. Why did you focus on the hours preceding the flight? Why was the reader’s role as spectator important?

I am fascinated by spectacle and our collective thrill-seeking gene, and I wanted the reader to feel the anticipation of the crowd. More universally, a reader is always both a spectator and a participant in a story. Reading is an act of voyeurism, is it not?

Invisible Cities breaks with traditional chronological narratives; there is a continual blurring of time and space within his book–Calvino himself posed a reader could experience the cities in any order they chose. What do you find most exciting about reading and writing nonlinear, nontraditional forms and why?

Nonlinear, nontraditional forms are closer to our interior experiences—our memories and emotions. When I read and when I write, I am looking for a ticket to someplace new—by which I mean a new vantage point from which to see and understand the world. I feel I’m more likely to find it with nontraditional forms, which hold more space for the unknown.

While the first half of Boundless blurs time and space, the second half is geographically contained and strictly chronological. During my research, I noticed that the Tribune repeatedly stated that all times listed for this event were “Chicago time,” occasionally specifying “Chicago daylight savings time.” So I became hyper-precise about the exact time in Chicago, sometimes down to the second, to the point where I hope the reader sees that this way of marking time is another manmade construct, ultimately a fiction.

I know that readers sometimes proceed in any order they chose, perhaps cherry-picking the shortest pieces to read first, but I believe the best experience of the book is sequential, in part because of its deliberate repetitions and recursions. Even in a nonlinear work there is a considered unspooling, and I’m guessing that most of Calvino’s devoted readers approached the book front to back.

The world’s fair section is peopled with individual characters such as Balbo himself, Madame Amalie Louise Recht, a Tribune reporter, a pickpocket, Melinda the Bearded Lady, Dodo the Bird Girl (inspired by real-life Koo Koo the Bird Girl), and others. Which point of view held the most personal significance for you to write and why?

I was most interested in the kaleidoscopic perspective of multiple points of view. The more time I spend researching history, the more I become aware of how fractured our understanding is. So much of our history has slipped through the gaps, so many voices have been left unrecorded, and no two people will view or remember an event in exactly the same way. In fact, no one person will remember an event in the same way over time. Perceptions and memories are shaped by knowledge and experience, by fears and desires. Each of my characters has a personal agenda for the day, whether it’s sneakily meeting a lover or picking a record number of pockets or finally getting a byline in the Chicago Tribune, yet they all come together for a moment as “a single living organism, each soul distinct and indistinguishable.” That said, if I have to choose just one to answer your question, I would pick Dessie, the future writer, constantly writing new versions of herself as she tries to discover who she is. I wanted to create a flicker of possibility that Dessie herself might be the author of the novella.

Dawn Raffel is the author of five previous books, most recently The Strange Case of Dr. Couney: How a Mysterious European Showman Saved Thousands of American Babies. Other books include two critically-acclaimed short story collections, a novel, and a memoir. Her stories have appeared in many magazines and anthologies, including NOON, BOMB, Conjunctions, Exquisite Pandemic, New American Writing, The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, Best Small Fictions, and more. Visit her website at www.dawnraffel.com.

Raised in Mexico City and the Midwest United States, Jael Montellano is a writer and editor based in Chicago. Her work, which explores horror and queer life, features in Tint Journal, Beyond Queer Words, Fauxmoir, The Selkie, the Columbia Journal, Hypertext Magazine, Camera Obscura Journal, among others. She dabbles in photography, travel, and is currently learning Mandarin. Find her on Twitter @gathcreator.