by Jael Montellano

My journey learning Mandarin began when the pandemic was still in swing. It began with wuxia and xianxia entertainment, but given my background, it sluiced into literature. I came across Yilin Wang’s translations of poetry, saw her endure erasure from the British Museum who used her translations without permission, how it perpetrated the thousand cuts of colonialism, and cheered for her when she was victorious and received their subsequent apology and settlement.

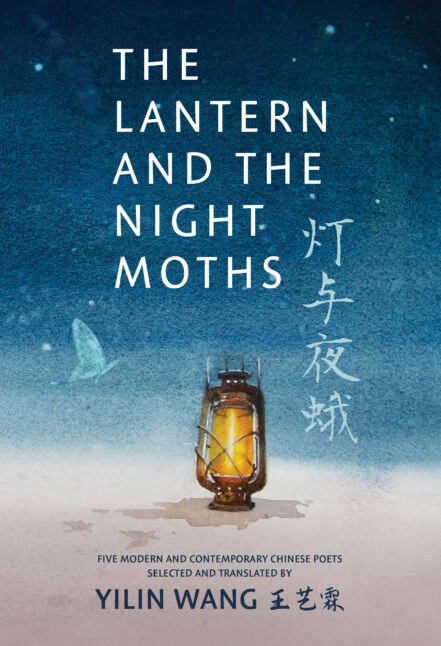

I was especially thrilled when her collection of translated poems and personal essays, The Lantern and the Night Moths (Invisible Publishing), released this year. The Lantern and the Night Moths features five modern and contemporary Chinese poets: Qiu Jin 秋瑾, Fei Ming 废名, Dai Wangshu 戴望舒, Zhang Qiaohui 张巧慧, and Xiao Xi 小西, and is interspersed with Yilin’s essays meditating on the selected poets. It alights a window into the richness of the natural world integral to Chinese poetry.

We corresponded to talk about the challenges of translation, her Sichuanese roots, and the elusive beauty of Chinese poetry.

Jael Montellano: When it comes to poetry in translation, I think the translator as much as the poet matters. I say this thinking about what is lost in translation due to a misaligned lens; I’m thinking of the recent translation of The Odyssey by Emily Wilson and what it has revealed about the characters of Penelope, Circe, Calypso, that was previously ignored because the prior texts were translated by men. In your book, I’m especially conscious and grateful for your sensitivity toward Qiu Jin, a cross-dressing feminist revolutionary, because of your background as a genderqueer feminist. Describe your experiences with Chinese texts translated by white sinologists and the importance of commonalities, not just contextual understanding, between a translator and poet’s lived experiences.

Yilin Wang: One of the reasons why I became interested in translating Chinese literature, especially poetry, is my frustration with the fact that many Chinese poets have long been and continue to be translated by white sinologists, some of whom have created very poor translations with problematic representation. Some of Qiu Jin’s poetry was mistranslated in this manner in the early 20th century, by a translator who completely disregarded the linguistic features and syntax of the Chinese text, and also neglected to consider her identity, beliefs, and the times she lived in. I’m frustrated as well by the practice of “bridge translation,” where a poet working in English (often white) is given some “literal translations” and “notes” from a so-called “native informant” who is bilingual, and then crafts a poem that they then proceed to call the translation. Often the English-speaking poet is celebrated as the translator, while the bilingual speaker aiding them is sidelined, and even more problematically, the translation that appears often ends up being more the poet’s fantasy of what the poem said rather truly reflecting an engagement with the words themselves. This practice of “bridge translation” continues with Asian poetry to this day, and it’s deeply upsetting to see poems that have been translated in this manner published, celebrated, and even occasionally winning awards. It reflects a very dismissive attitude towards the work of actual translators, especially translators of color, and shows how ignorant some people can be about the art of translation.

In your essay “On Dai Wangshu: Poetry is What Survives Translation,” you delve into Dai’s experience as a translator/poet himself. He translated French, Spanish, Italian and Russian literature into Mandarin, and you mention his immersion traveling, the ways he enriched himself to feed his translation, and the parallels you yourself have taken. As I read this, I experienced a kinship even as a fiction writer; how I approach characters in fiction and immerse myself in their interests to better slip into their skin, know their thoughts, what influences have shaped them that will lead to the decisions they’ll make. What role does this play in translation for you?

What frustrates me when I am reading certain translations of Chinese literature, especially some dated translations by white sinologists from decades ago that are still widely taught and held up as classics, is that they seem to view translation as a very academic, anthropological, and almost technical exercise, where a source language text is simply one to be studied and handled like a museum object. It’s an approach that’s quite cold and impersonal, far removed from lived experiences, the body, ethics of representation, and the actual worlds being inhabited by the original writers.

As someone who comes to translation from the perspective of a writer, I see translation much more as a type of creative writing. As you mentioned, many writers will try to step into the characters and worlds they create, to bring it to life. Why can this not be the case for translation as well? When I write, I will listen to period music, work in coffee shops or settings related to what I am writing about, look at photos, try to immerse myself in the worlds I am building – I try to practice the same as a translator. I want to consider the writers’ perspectives, step into their shoes, honor them, think about what their intentions were, the circumstances in which they created the works.

As an immigrant who writes only in English as well, I understand the loss of history, culture, language, that comes from displacement. In fact, I recall reading a text recently that said migration is so painful, there must be extreme reasons for doing it. In your essays for Zhang Qiaohui, you note your ancestral hometown of Sìchuān, the Yíbīn dialect, your grandmother’s guidance in re-teaching you Mandarin and Sichuanese, this tether to your homeland, which has allowed you to turn to translation. What was this re-learning process like for you? Tell me about your wàipó.

As someone who moved quite frequently during my childhood, living in six cities on two continents before I reached age eleven, I am no stranger to displacement. In my essay “Faded Poems and Intimate Connections: Ten Fragments on Writing and Translation,” I write about how I was exposed to Táng dynasty poetry when I was very young and how this led me to fall in love with language. Yet, I moved to the US with my family around age 4 or 5, and after a few years, I quickly lost all my Chinese skills due to completely being immersed in an English-speaking environment. My family sent me back to live in China, where my wàipó, an elementary school teacher, re-taught me Sichuanese and Mandarin from scratch, giving me a solid foundation in the languages that I now rely on every time I pursue translation work.

It’s so much easier to lose a language than to learn or to maintain it. Even with the solid foundation offered by my wàipó’s lessons and three years of education in China, after I moved to Canada in my preteens, I once again found myself in an English-speaking environment, especially once I decided to study literature and creative writing extensively in high school and at post-secondary. It took me until I was in my BFA and MFA programs to become conscious of how extremely eurocentric my literary education was, and I started consciously seeking out more Chinese literature (in the original language and in translation) to fill the gaps. I took up literary translation in part as a creative practice to engage with Chinese literature in deep, meaningful, and personal ways that I’d never get to do otherwise.

I feel that translators are very often disregarded, especially with modern technology; we have translation apps on our phones, access to automatic sites that spit out text in seconds. There is this culture of immediacy that trickles into the literary world. I’ve had this thought reading through rushed or automated translation as I study Mandarin, that literary translation requires a writer. Even in my toddler understanding of Mandarin, I found myself reading the Mandarin text included opposite your English translations, going, Yilin is so skilled. What beautiful choices she made. May we talk about the speciality of translating Mandarin?

Mandarin Chinese and English are such different languages, as you know. Chinese does not have tense, prepositions, definite and indefinite articles, and numerous linguistic features that are often taken for granted by English speakers. It’s even more difficult if we are talking about Literary Chinese, the language used by writers and scholars for works of literature up to the early 20th century, including Qiu Jin, and which also influenced the works of poets such as Fei Ming and Dai Wangshu, who wrote in the transitional period between modern Mandarin. In Literary Chinese, nouns, verbs, or other keywords are regularly omitted from lines of poetry, leaving gaps for the reader to simply infer through context or common sense. What’s more, poets also love to fill their poems with allusions to classics and past works (which can number in the thousands, requiring poets to undergo years or even decades of study). Similarly, they rely on a large body of imagery each with set connotations-–for example, spring flowers or the autumn moon—all of which would need to be contextualized for the English readers for full understanding. All of these elements work to give Chinese poetry a lyrical, concise, and sometimes elusive quality, which I love. It also creates immense challenges for the translator.

I have familiarity with the late Táng poet Li Shangyin and felt, as I read your translations of Fei Ming’s work, a similar call to the ephemeral, to mystery, that is present in both poets’ work. To my delight, you also remarked on this in your accompanying essay “On Fei Ming: To Translate Nothing and Everything.” But you encountered difficulty translating Fei Ming’s work because of this quality. What do you do when you are handling not only language which is abstract, but which carries cultural meaning and context that simply isn’t present in Western language? I’m thinking of the example you gave of “positive emptiness.”

Fei Ming is one of my favourite modernist Chinese poets. Translating his work has been a lesson in how to handle ambiguity as a poet and translator. Through engaging with his poems, and also my deep dive into literary history to understand why he approaches his work the way he does, I have learned to embrace the elusive quality in his poetry as silences that are left intentionally for the readers to embrace, dwell in, and experience, rather than something to be explained away. There is a lot of beauty in that.

When I encounter lines or works where there is a lot of cultural context, I try to be very deliberate about word choice, going not necessarily for literal translations, but words that I think convey the tone and emotions best. I rely on a wide range of tools, like glosses, footnotes, or translator’s notes. Sometimes, I leave things unexplained, with the expectation that an engaged and curious reader could do more research by themself if they wish to. I think of the title of my essay about translating Fei Ming’s work – “To Translate Nothing and Everything” – when I translate Fei Ming’s work, I’m also honoring the gaps and the unsaid, and there can be so much richness and nuance in the inexpressible.

I have read across languages and cultures for as long as I can remember, so I’m endlessly fascinated by translation and the translation process. Could you take me through your process? Let’s take a beloved line in Mandarin and journey through it together step by step to discover how you reach your endpoint.

My process varies a lot depending on the poem I am translating. In general, I began by close reading a poem in full multiple times, annotating as I read it aloud, identifying its various emotional turns, use of literary devices, and stylistic features. Once I finish that, I complete a rough draft of the poem, line by line, starting with a close, more literal translation of the words on the page.

I’m going to use the opening line of “the floating dust of the mortal realm” 《飞尘》by Fei Ming, which I discuss in my corresponding essay, as an example. The line as written in Chinese is “不是说着空山灵雨”. “不是说着” is fairly straightforward, meaning “to not say” or “to not speak of.”“空” is often translated as emptiness. “山” is a mountain or mountains. “灵” is a very difficult-to-translate adjective describing people or things that possess a light, airy, and transcendental quality and keen spiritual awareness. “雨” means rain.

Read together, “空山灵雨” paints a mythical scene of empty mountains and mythical rain. However, English words like “emptiness,” “void,” “vacant,” and “deserted” tend to all suggest a lack, and fail to capture the airy, meditative, and ephemeral quality of 空, which is also the Chinese word for the Buddhist word śūnyatā. “灵” isn’t simply just about being spiritual or magical; it implies the rain is falling in an elegant and moving way, almost as if it were a living being, coming just at the right time.

After coming up with a rough translation, I did more research on the phrase, tried out many different word combinations, consulted the thesaurus to explore synonyms I never considered, and even talked to a scholar of Buddhism to clarify my understanding of “空” and its fit with the rest of the poem and Fei Ming’s other poems, and I eventually settled on the translation “not to speak of timely and wondrous rain falling upon ephemeral mountains.”

There is a quote in your book from your essay “Faded Poems and Intimate Connections: Ten Fragments on Writing and Translation,” in which you write “[b]eing an immigrant in the diaspora can often feel like drifting in a vast ocean with no shorelines in sight…poetry…[is] the closest that I have ever felt to belonging.” I was, and continue to be, so moved by that quote and consider the whole volume of five poets and your essays as a kind of conversation, a conversation across time, both with the poets, but also with ourselves, the child selves that were left on the shores of our homelands, and our adult selves seeking our bearing, and across distance, with other diaspora members. Can you talk to me about the concept of the zhīyīn and the intimacy you feel with these poets you’ve selected?

Thank you so much for your kind words. In my book, I explain that a zhīyīn 知音, which literally means “someone who truly understands your songs,” is a word for a kindred spirit or close friend. As someone who identifies as aromantic and asexual, I really resonate with the word, which can be used to describe a queerplatonic soulmate with whom you share deep connections and ideals.

I absolutely think of translation as a conversation–across time, place, and the page–with the poets I translate, whether living or deceased, with myself as a poet and translator, and with the readers who encounter my work, especially those in the Sino diaspora. It’s such an intimate process grounded in reading, reflection, and engagement. So for me, the word zhīyīn really helps to encapsulate the kinship I feel with the poets I selected and whom I am collaborating with. Qiu Jin, in particular, wrote frequently about her longing for a zhīyīn, and her poems inspired my approach to thinking about this concept as well.

Yilin Wang 王艺霖 (she/they) is a writer, a poet, and Chinese-English translator. Her writing has appeared in Clarkesworld, Fantasy Magazine, The Malahat Review, Grain, CV2, The Ex-Puritan, The Toronto Star, The Tyee, Words Without Borders, and elsewhere. She is the editor and translator of The Lantern and Night Moths (Invisible Publishing, 2024). Her translations have also appeared in POETRY, Guernica, Room, Asymptote, Samovar, The Common, LA Review of Books’ “China Channel,” and the anthology The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories (TorDotCom 2022). She has won the Foster Poetry Prize, received an Honorable Mention in the poetry category of Canada’s National Magazine Award, been longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize, and been a finalist for an Aurora Award. Yilin has an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC and is a graduate of the 2021 Clarion West Writers Workshop. Find out more at www.yilinwang.com.

Jael Montellano (she/they) is a Mexican-born writer, poet, and editor. Her work exploring otherness features in La Piccioletta Barca, ANMLY Lit, Tint Journal, Beyond Queer Words, Fauxmoir, The Selkie, the Columbia Journal, and more. She is the interviews editor at Hypertext Magazine, practices a variety of visual arts, and is currently learning Mandarin. Find her at jaelmontellano.com.