Steven Spielberg isn’t the only guy interested in exploring the multiplicity of Abraham Lincoln’s life and death. In 2004, after President Reagan’s death, writer Kurt Kennedy became curious about one of the United States’ most despised and beloved presidents – Abraham Lincoln. He started by devouring research on Civil War embalming techniques and Lincoln’s funeral train. Laying Lincoln Down tells the story of Lincoln’s funeral train from the unexpected perspective of Lincoln’s embalmer, Henry P. Cattell, who was one of more than 300 people to accompany “The Lincoln Special” on the entire 1,654 mile funeral procession route which retraced Mr. Lincoln’s cross-country journey as president-elect in 1861. And since there is always more than one way to tell a great story, Kennedy has also created a graphic novel version of Laying Lincoln Down with artist Dan Bauer. Kennedy sat down with HYPERTEXT’s Emily Roth to discuss the research, writing and art of this incredible and complicated project.

HYPERTEXT: Can you tell me a bit about your history as a writer? How did your interest in graphic forms first start?

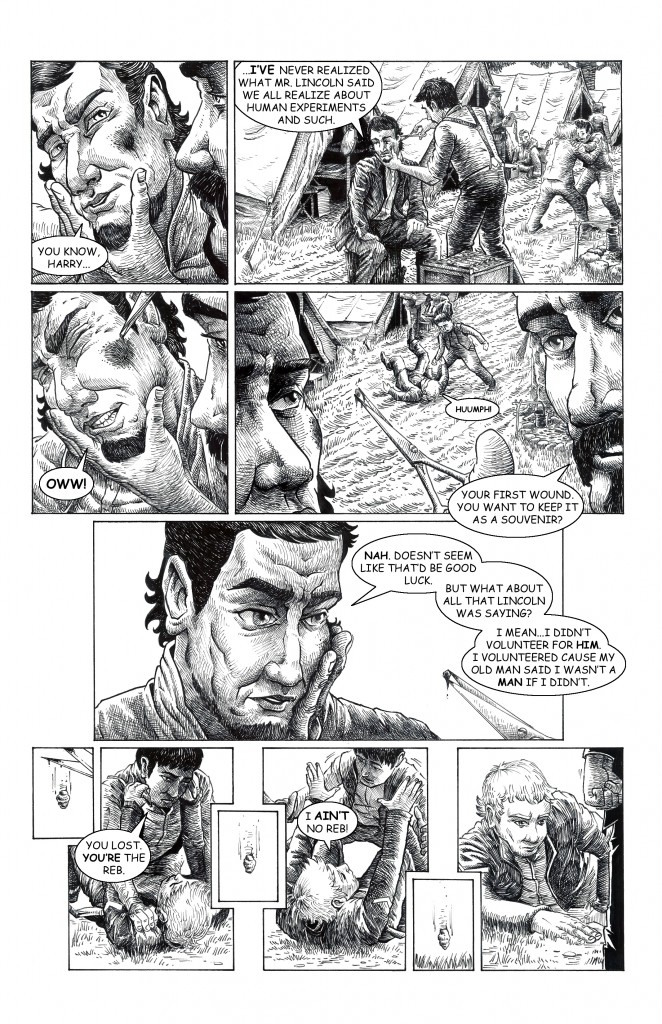

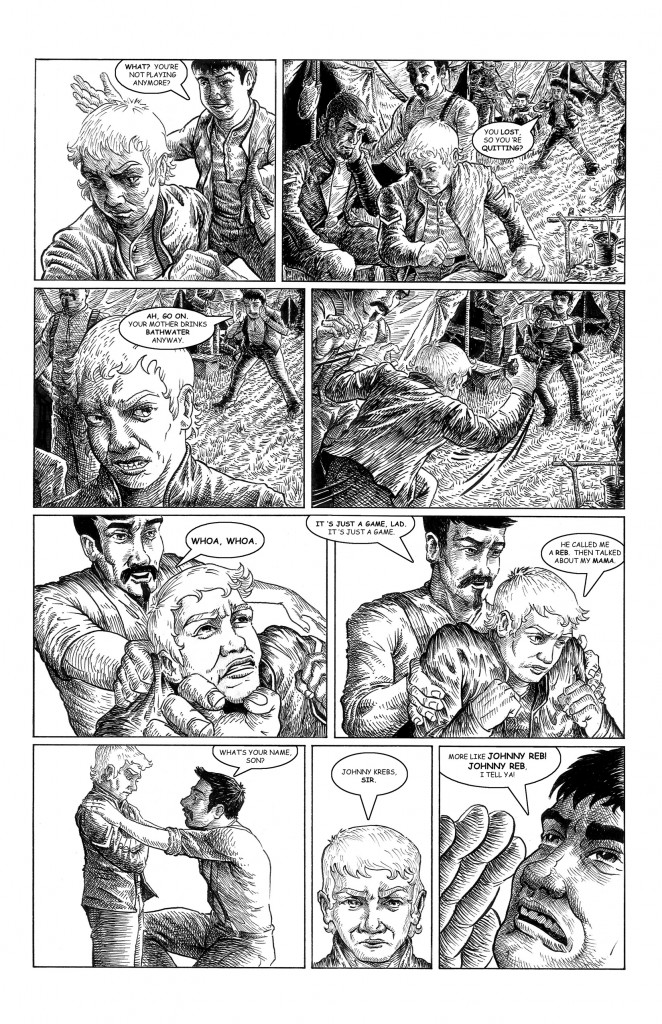

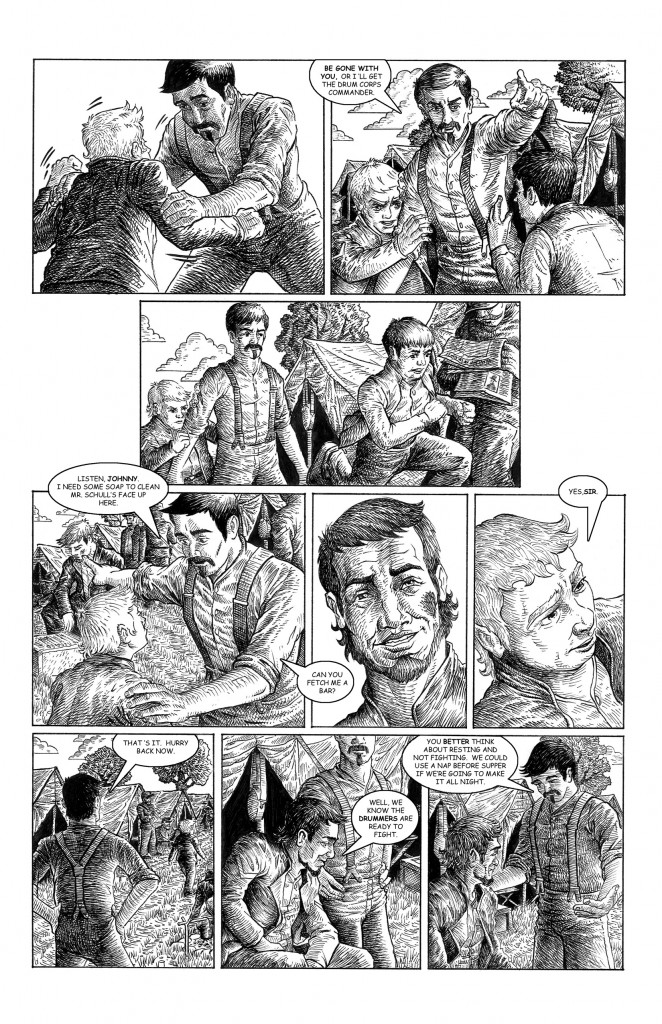

Kurt Kennedy: I started journaling in my cinderblock dorm room as a freshman in college, then attended graduate Creative Writing programs at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and Columbia College Chicago and got better. I drew a lot as a kid but never trained professionally. The awesome art in Laying Lincoln Down is the work of my friend and creative partner, Dan Bauer, which is good because I can gloat on it and not sound conceited. My interest in graphic forms started as a kid, liking comics. A lot of the Dark Horse Star Wars stuff and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns were favorites of mine. Also, I bet few people can say they have every issue of Fright Night.

HT: When did you first become fascinated with Abraham Lincoln? When was the first spark of inspiration for this project?

KK: The Civil War was my favorite part of high school history class and I’ve always been intrigued with Lincoln the demigod, like most Americans, I think. (Try taking notice sometime of how often you see an image of him in your daily life.) My fascination grew while researching for this project.

The idea to write a story about the funeral of Abraham Lincoln actually was sparked by the death of Ronald Reagan in 2004. For the last several years of his life, most of what was said about him in the media was negative. Did he have Alzheimer’s while in the White House? Etc. But, when he died, it was like a switch flipped; nothing but comments about what a beneficent and magnanimous man, and a strong President, he was. This phenomenon of positive outpouring following a controversial, prominent person’s death interested me. I started asking myself ‘Who is the most interesting person around which to write about this situation?’ Lincoln seemed the obvious choice. (I think people are beginning to realize this again with the help of books and movies about him, but he was probably the most polarizing U.S. President ever; truly hated by many. His election prompted the secession of the Southern states, after all. I imagine our current political milieu multiplied several times.) The cool story of the funeral train journey was a bonus discovery after beginning research.

HT: How concerned were you with historical accuracy in your writing? How concerned has Dan been with the historical accuracy of the art?

KK: Laying Lincoln Down is a work of historical fiction. It’s accurate on many levels but also takes liberties for the sake of telling an engaging story. Dates, times, and things like the weather on given days are accurate based on sources: where the train was when and the associated ceremonies, battles featured in the flashbacks, etc. The events of the era very much helped determine the plot; things like Henry P. Cattell, the embalmer and main character, answering Lincoln’s 1861 call for 75,000 volunteers.

One major thing that is altered from what actually occurred is that Harry did not accompany the body on the train. His employer and stepfather, Dr. Charles Brown, did. (Cattell’s name was printed as “Harry” in one source and I adopted it as the fictionalized character’s nickname, to bring some life to this person whose recorded biography is limited.) Cattell indeed performed the embalming and, for the sake of continuity and to take optimum fictional advantage of the Harry/Charles relationship, I felt it was necessary to put him on the train and make him the main character.

It’s the same thing with the art. Dan called me a few months ago to talk about a Union-Army-issued coat Harry will be wearing in some panels. He had found a picture of a soldier in a Texas regiment wearing a coat that he liked the style of, and wanted to use it. I said “Go ahead,” even though Harry is in the Pennsylvania Infantry. Civil War buffs know their stuff and, judging from what other authors of the subject have told me, I expect we’ll probably get called on some things. But this was an opportunity to give my artist some stylistic freedom and, hopefully, a deeper sense of personal involvement in the project.

I hope folks are sympathetic to the decision to fictionalize in order to bring out the essence of this story we want to highlight from history.

HT: How much research went into the project, approximately?

KK: It’s difficult to quantify the research for this. But, as mentioned, I’ve had this idea for about eight years, and I’m just now closing in on completing the rough draft. I read and look things up all the time. I still have tidy-up, fact-checking research to do in the editing phases. One thing I can say for certain about the research is that it has been, and continues to be, fun. It’s included a lot of traveling, learning, and meeting nice, helpful people.

HT: What are some of the inherent challenges with creating a compelling narrative where images have more weight than words? Does Dan struggle with the complexity of the images themselves?

KK: To be honest, I think writing for graphic forms may be slightly “less challenging,” if you will, than prose writing. The task of captivating the audience is still there but you don’t have to explain as much in words, or have that mild-but-always-present nagging worry over the quality of your prose. (Of course, you don’t want the dialogue to be cheesy.) The images say so much in a graphic novel. If the writer and artist develop good communication and trust each other, it’s kind of liberating as the writer to describe what you want to see from panel to panel then just sit back and let the artist do their thing.

I’m in good hands with Dan concerning complexity of images. At times, he’s suggested page layouts that were much more visually engaging than what I had described. If you’re working on a collaborative project, I think it’s real important to be malleable and let each person run with their role. If not, then why collaborate?

As with all writing, you have to have a strong sense of what you want to convey to the audience, and be able to communicate it.

HT: What is the greatest challenge with the actual writing of a graphic novel?

KK: Once you get accustomed to writing in the script format, which isn’t too difficult if you think of it simply as the parameter within which you’re working, the biggest challenge of writing a graphic novel is the same as writing a prose novel or anything else: making sure you’re making the time to do it.

Laying Lincoln Down will be published by Wicker Park Press/3i Books in late 2013.

Emily Roth is a native of Kalamazoo, Michigan, and recent graduate of Columbia College Chicago’s BFA in Fiction Writing program. Her writing has appeared in the Story Week Reader, Backhand Stories, Echo Magazine, and HYPERTEXT.