By Anita Gill

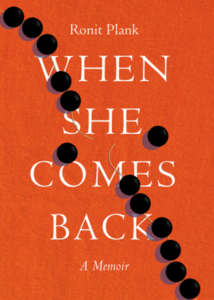

Ronit Plank’s debut memoir When She Comes Back begins with the epigraph from Mallika Rao’s “Why I Hate Gurus” in Vulture: “A soul in belief is a delicate thing—it can be exploited or liberated, depending on the circumstances.”

In this coming of age story, Plank endures a childhood where her mother was in and out of the picture. After her parents’ divorce, her mother became a sannyasin for the now-infamous Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, the self-described spiritual guru who established the Rajneeshpuram camp in Oregon. While Plank’s mother seeks a sense of personal meaning within the Rajneeshi cult, Plank herself searches for a sense of belonging within her family.

I first crossed paths with Plank while at the Pacific University low-residency program where we both completed our MFAs in Nonfiction. Thanks to social media, I have followed Ronit as her literary career has flourished. Her essays appear in notable places such as The Atlantic, The Rumpus, and Huffington Post, and she currently hosts the podcast And Then Everything Changed. Plank and I recently had a conversation where we caught up on each other’s writing journeys, talked about unraveling the uncomfortable memories, and noted how the voice of Debra Gwartney, our mutual MFA mentor, still echoes in our daily artistic practice.

Thanks so much for spending your afternoon with me. It was such a pleasure to get to read your debut memoir! As I recall, you started writing in fiction. What drove you to move into nonfiction?

I had written for the theater when I was acting in L.A. When I had my second child I went to a writing class at the University of Washington in fiction. I really liked it. It was never in my mind that I would write, and I thought short stories were great.

When I enrolled in the Pacific University low-residency program I had already published a few short stories and I wanted to write a novel. The general advice in the program was not to focus on writing one novel, and unfortunately I didn’t advocate for myself to stick to the novel project. After struggling halfway through my first semester, I thought to try nonfiction. A lot of my fiction stemmed from things I had gone through. My work was about relationships and families and not being seen.

I love memoirs about family dynamics and yours focuses on your childhood, while also including reflection as an adult looking back. What was your experience in pulling back the curtain to write this book?

There were so many phases. The book that I started off was my thesis at Pacific. There were a lot of revisions and a great deal of sifting through memories to understand their resonance. Debra Gwartney was my first teacher who really explained what it was to write a memoir. I had misunderstood the genre before and worried it might be navel-gazing. Vivian Gornick explained memoir is about looking for the role you played in what happened to you and how you perceived it. Those were the keys that unlocked what I wrote about.

There were so many phases. The book that I started off was my thesis at Pacific. There were a lot of revisions and a great deal of sifting through memories to understand their resonance. Debra Gwartney was my first teacher who really explained what it was to write a memoir. I had misunderstood the genre before and worried it might be navel-gazing. Vivian Gornick explained memoir is about looking for the role you played in what happened to you and how you perceived it. Those were the keys that unlocked what I wrote about.

My reflections on the past kept changing and unfolding. When writing memoir, you cannot be resolute in any kind of impressions you have about what happened. For me, one of the prevailing experiences of writing it was finding a lot of empathy for my parents. I think empathy drove me to write it, but it also reaffirmed my empathy for them. I never sought to throw anyone under the bus while writing it. I think that’s an important distinction when writing a memoir about other people.

When Debra asked me what part I had played in all of this, I was stumped. I had been a small child when a lot of this happened. I thought she was asking what was the blame I held or what I perpetrated. But that’s not what that means. It’s about pattern-making and reflecting on why the things that happened to you affect you the way they did and why you did what you did with them. That’s what makes the stories our stories. The way I responded was different to how another child would have responded.

I appreciate your point about the level of empathy it took to write about your parents. In the process of writing this memoir, did it allow you to see your parents differently?

I knew a lot of their story, but when I grew up hearing their story—as a kid, as a teenager, as a young adult—it was very different than looking at it again with fresh eyes. It’s really easy to vilify parents, but what created my experience was the result of what created their experience. This doesn’t let everyone off the hook for not taking care of the family, but I don’t think anyone did anything with the intention of being cruel.

I’m lucky because my parents now live very close to me. We now have Shabbat dinner every Friday together. We’ve had a lot of opportunities to talk about what happened to our family and my father is really regretful. He’s mentioned to me on more than one occasion that he’s sorry he left the family when he did. I hadn’t really heard that before.

I always thought adults knew what they were doing. But nobody really knows what they’re doing. I’m still making it up as I go along. I mean, how are people who had no good example of how to love and how to be vulnerable in their own lives growing up supposed to do that? And then how are you supposed to grow a family when you can’t be vulnerable with your partner? I had my own troubles trying to figure this out, so my empathy for them grew because it’s not as easy as I thought.

Your memoir takes us through different forms of faith-based communities. It starts with your childhood on the kibbutz in Israel. Not long after your parents’ divorce in the U.S., your mother develops interest in the Rajneesh group, even going to the ashram in India and later to the compound in Astoria, Oregon. Also as an adolescent, many important events happened when you were in a Jewish day camp in New York.

This is what I mean about memoir. I didn’t realize until later that the loss of my family was so painful because within it I had lost my community, too. It wasn’t just a divorce. It wasn’t just moving to a new country. It wasn’t just losing your language and your friends. It was losing your entire point of gravity. Had I understood the impact of losing this safe nest then I would have understood why I had gotten so anxious as a kid.

The safety of a community was so important to me. I loved summer camp because it had these rules. I loved doing theater and I realized later that part of the reason I loved it was because I had my community for the weeks we would do our shows. You were in a cast, practice for a few months, and then do a show. For me, it felt like my nest was back. I felt safer in a community. The same started when I would find a community of writers. It made me so happy because it was so predictable.

I didn’t realize it until writing the book how much summer camp saved me. We would go for many summers. It was a safe and comfortable place to be without a lot of surprises.

I was amazed at your adept precision in unpacking your discomfort around your father as you progressed into your teenage years. As you became more aware of your sexuality, you had an intense amount of inner anguish when spending time with your father, the parent you felt most connected to. Was it difficult to be honest on the page?

I did not want to do it and it was where I was most apprehensive in sharing my discomfort with my father. I had to ask myself if I was ready to talk about this and if I wanted to let my father know. Back then when I was growing up I didn’t realize I could be an advocate for myself and ask for more space from him.

I don’t know if my hesitancy to say anything when I was young was because I thought it was my problem or how much of it was my fear of making him angry. What do you do when you have only one parent that’s showing up for you? What happens is you really don’t want to make them mad. That was my first crisis of attachment with my father after he had left the first time. I needed more room and I didn’t have it and I didn’t ask for it.

So yes, I didn’t want to write about this because I don’t talk a lot about sex. It’s just not my area where I dwell usually. It was a little more snaggy. But I think it’s important. You have to have this piece where one parent is leaving and the other one presents a different problem.

I know that you sent your manuscript to your family before publishing it. What was the reaction?

Once I had the publishing deal, I felt strongly that they should read it. My feeling is if your manuscript deeply concerns other people, then it’s important to share it with them before you publish it. I think it’s important to let them see what is about to happen.

My sister was able to tell me things I had forgotten, which I then added into the manuscript. She was the one that pointed out certain memories I had gotten wrong. I had forgotten that she’d hyperventilated during a fight we witnessed and I’d brought her to a window to breathe. Or that when we got the news that our mother was going to Oregon, she reminded me that we got the letters while at camp. I had blocked it out. That’s really important and it shows your memory can be so fallible. It’s telling you things and yet it’s also hard to pin down. I was so grateful I had a sibling who had been a partner and witness for all of these events. I understand memory is fluid and there’s no set truth.

My father, however, gave me nine pages of single-spaced notes. He had geographical and timeline corrections and he fixed my Hebrew. And then he had some qualms with the memories. He felt I was not accurate with the memories here and there. A few times I had to go to bat when talking to him about these events. I felt I had to go and fight for my story again.

My mom had seen earlier versions in essays. She was relieved and to some extent thankful that this version of events had the empathy and perspective that it did. And we are closer now than when I finished the manuscript.

What were some of the biggest craft-level obstacles when working on this memoir?

It helps for me to have some sort of a structure. Debra told me to write the really important scenes that need to be in my memoir. What 10-12 scenes really need to be there? I narrowed them down, hoping that I had enough. A lot got left on the editing floor because it didn’t drive the action forward or did not add anything to knowing who I was.

Then I got a note from one of my editors Jason Allen, a fellow graduate from Pacific, who urged me to start with more scenes. Not all of my chapters started in scene. Most fiction writers know to get the action cooking right away and I had to really try hard to put the scene before the more general information. By starting with the action I could earn my way into talking about day-to-day life and then get to the heart of what was going to happen in that chapter.

Another issue for me is just writing a scene. It feels like I’ve entered a room and I have to unpack my bag and hang up all of my clothes, metaphorically, because I have to dig in. It’s so much easier to tell—I don’t want to show it. I’m writing fiction right now and I enjoy writing scenes there.

Sometimes readers don’t need a whole lot in the scene. You don’t need to spend pages and pages making your scene. You just need enough to ground us in space and give us a little bit of sensory. It goes a long way.

Yes! Writing scenes mean I have to slow down and I struggle with that, too. Speaking of fiction, could you tell us about the novel you are working on?

I’m working on two projects. The first is a nonfiction project that will be an interview-based and history-based nonfiction book, peppered with some personal anecdotes.

The fiction is a novel I had begun before Pacific. I had written a flash piece that’s recently gotten honorable mention in the Craft literary journal contest. My sister read it and loved it so much that she told me she’s dying to know more about the characters. My sister is the one who encouraged me to start writing years ago. She knows me better than I know myself. I’m writing this for my sister!

I am now returning to this story from before the MFA. What was blocking me before was that I was too critical of myself. I thought no one was going to want to read this. I just kept thinking that no one would believe my writing. Now, I have made a goal to write 1,000 words a day on it.

It’s shaping into a young adult novel. I was shying away from naming that because it initially wasn’t what I wanted to write. But after my sister told me her thoughts and I started writing on it every day I realized I needed to stop caring about what I wanted it to be and allow it to unfold. Now I’m excited! I want to know what happens to these characters. I’m thinking about them all the time, which is different from my experience when I was writing in memoir. I enjoy writing the scenes and I can’t wait to see what they do next.

After I finished writing the memoir, I thought I’d never be able to write in fiction again. But then, this collection of short stories I’d written at the beginning of my writing journey, Home is a Made-Up Place, recently won the Eludia Award from Hidden Rivers Arts and is set to be published in 2022. That’s when I remembered that I really love writing fiction and I should try it again.

What are some memoirs you are reading right now that you recommend?

There are a couple of memoirs I’m reading right now: Emma’s Laugh by Diana Kupershmit about giving up and reclaiming a differently-abled child and Inside Passage by Keema Waterfield about parental abandonment, addiction, poverty, and the pursuit of art.

When I think about memoirs that really guided me I think of Live through This by Debra Gwartney, The Iceberg by Marion Coutts, Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward, This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff, and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby to name a few.

Could you tell us a little about your podcast?

I love to hear about people’s lives and stories. I want to understand how people have lived through events. I’m also really fascinated by relationships. I love family origin stories. As I started writing my memoir, I realized that so many people have stories about resilience. I started this podcast a year ago and I interview all kinds of people: authors, survivors, people in recovery, social justice leaders, people willing to share their story with vulnerability. We talk about the pivotal moments in their life and the decisions they feel have defined them. The podcast is called And Then Everything Changed because I center the interview around what was your reality like before, what happened to change your life, and how is living this way better.

Our lives are a lot messier than a book or a movie, but the writer in me loves to find the thread in a life and make a story out of it.

Buy When She Comes Back from your favorite indie bookstore or find it HERE.

Photo courtesy Mandee Rae

Ronit is a writer, teacher, & podcaster with work in the The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Rumpus, The Iowa Review, and American Literary Review among others. She is host & producer of the award-winning podcast And Then Everything Changed featuring interviews with survivors, authors, thought leaders, and people in recovery about pivotal moments in their lives & decisions that have defined them. When She Comes Back, her memoir about the loss of her mother to the guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh is her first book. Her short story collection Home Is A Made-Up Place won Hidden River Arts’ 2020 Eludia Award and will be published in 2022. For more about Ronit and a complete list of work visit: https://ronitplank.com/

Anita Gill is a writer, editor, and recent Fulbright fellow in Spain. Her essays, memoir, and satire have appeared in The Iowa Review, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Prairie Schooner, The Offing, The Baltimore Sun, and elsewhere. Her writing has been listed as Notable in Best American Essays and has won The Iowa Review Award in Nonfiction. She holds an MA in Literature from American University and an MFA in Writing from Pacific University. Follow her on Twitter @anitamgill.