In my first semester studying creative writing, the teacher of a Fiction Writers and Publishing class asked why each of us enrolled in his course.

“To make money,” I said.

A fellow grad student, ensconced in black and with a name like a fruit, sneered, “Why does it all have to be about money?”

It didn’t and it doesn’t, Fruit Girl, unless you want to earn a living at it. And I do.

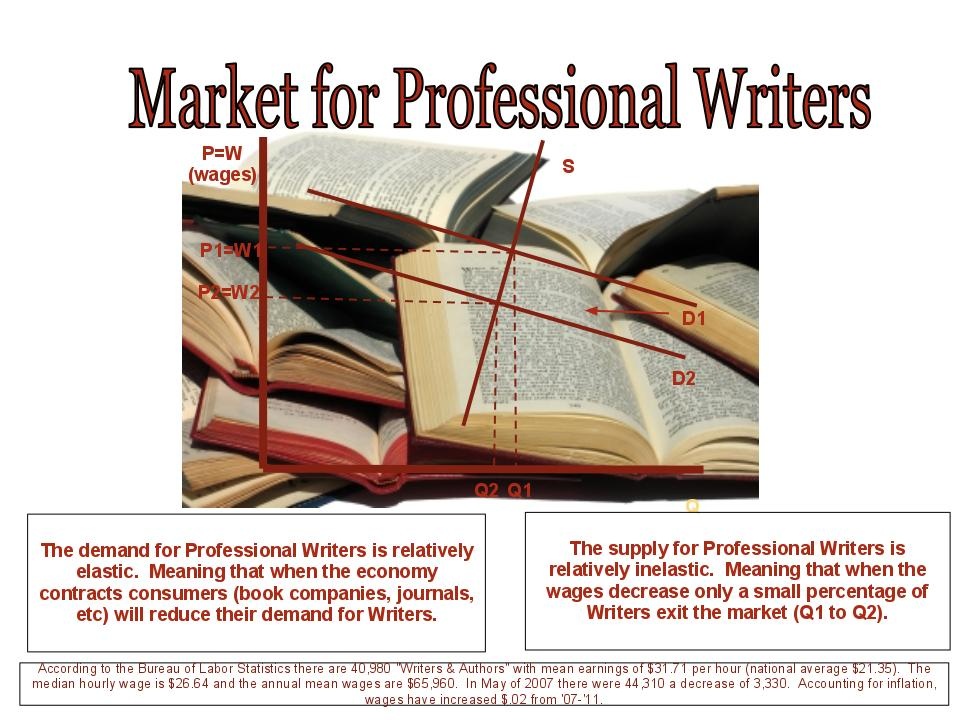

From the onset, it seems, I knew it’d be tough living as a writer. Probably why I studied business and economics in my undergrad, even as I spent more time reading and writing than charting my supply and demand curves. (Incidentally, the supply curve [# of writers] is inelastic. That’s to say we’ll write without pay. This subverts the core of economic assumptions: writers do not behave in a rationale manner. See Figure 1.1 Copyright Peter Duffer, Image courtesy of Duffka School of Economics).

***

During my undergrad studies, my mom died. On her deathbed she exhorted me to make money. Might’ve been the morphine, or it might’ve been a moment of lucidity. Little did I know at the time that I had one final, eternal act of rebellion: I would embark on a writing career.

I backpacked around our country, tried writing a novel about a college-aged guy who deals with his mom’s death by traveling around the country looking for a home, and realized unequivocally that my writing was shit. So I got my first real job at the Options Exchange. I’d been working legally since I was fifteen, mowing lawns since I was ten, and I bartended to pay for my last two years of college, and of the dozen menial jobs I had there wasn’t one that I hated more than the Options. I stuck it out for eight months before liberating myself to a Colorado ski job.

I couldn’t be a ski bum forever but I was encouraged by the promise of writing every day. I enjoyed it as much as skiing. Must’ve been the altitude. Since I always knew how to make money, and with a modest inheritance (an unusual safety net for a guy in his mid-twenties), I moved back to Chicago to enroll in an MFA Writing Program.

A decade later, I make as much money as I did that first year at the Options Exchange. That was entry level. Now I have two kids, a mortgage and a wife who works her ass off.

I hear ya loud and clear, Ma.

And every week I swing wildly between material yearning (as manifest by career accomplishment) and a forced sort of Zen contentment (ohm…I’m alive today…ohm).

I teach part time, do the freelance hustle, finish writing projects with the same time equation as projects around the house:

finish novel= hang ceiling fan

It should be done this weekend, but the wiring is fucked, there needs to a brace in the joist, and that character has too big a role to be so one-dimensional.

***

I’m home with my kids four days a week and despite the scheduling problems, I love this set up. Last night I finished a play, this morning we go to soccer (and yes, goddamnit, I will drive my minivan); the vicissitudes are exciting, enriching, and, on good days, seen as a blessing.

But every two weeks I freak out. When my wife is on call, tacking on an additional 10-15 hours of an already strenuous job, I freak out. When I look at my outward accomplishments, my career milestones covered in moss, I freak. When I look at my kids’ teeth, their appetites, their birthdays, the couch that no longer fits us, the house that will soon follow, I fucking freak.

I made a choice. It didn’t feel like much of a choice this summer when my class got cancelled, two of my freelance contracts expired, and a dozen resumes went out with zero response. If I made more money, or at least had a more consistent expectation of income, I might feel more confident in my career. Most likely, I would want more, but I wouldn’t be considering alternative careers every time the money stopped coming in. I could have a different job and write around it—I’ve done it before. But I don’t want to. This is my career, so this is my career dilemma.

***

Most people likely have a formula for career expectations like this: as skill advances, income increases. In economics, these are called “returns.” The returns for a writer cannot be graphed. Increased esteem, maybe; more realistic expectations, definitely; greater income? Get fucked.

This notion too reminds me of college. A favorite teacher, an iconoclast whose position in the business school was always threatened, lived by the maxim, “Do what you love, money will follow.” This was reinforced in that first fateful semester of my MFA, when I read an article where some guy said it takes ten years of writing before you started to figure it out. I scoffed. Now I scramble.

What is the security of other jobs now, though, especially with endangered pensions and tote-bag benefits? Given what I love about this set up and what I hated in the past, there would be a significant trade off for that security. (Here comes that forced Zen contentment.) Maybe I just lack the clarity of hindsight at this point. I’m pretty close to where I wanted to be five years ago, so maybe the current anxiety is paving the road for the next five. Ideally, my reality stops chasing my expectation and the two find a sustainable, enduring equilibrium, the point of idealistic efficiency. That balance remains elusive.

About the author…

Robert Duffer’s (www.robertduffer.com) work has appeared in MAKE Magazine, Chicago Tribune, Monkeybicycle, Time Out Chicago, Annalemma, Chicago Public Radio, Word Riot, New City, Flashquake, Chicago Artists Resource, Pindledyboz, The 2nd Hand, and other coffee-table favorites like Canadian Builders Quarterly. He writes the weekly column, Experiments in Manhood.