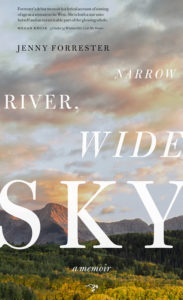

HYPERTEXT MAGAZINE ASKED JENNY FORRESTER, AUTHOR OF NARROW RIVER, WIDE SKY, “WHAT QUESTION DO YOU WISH YOU’D BEEN ASKED ABOUT YOUR WORK?”

“How could you vilify your family members and a whole small town in your book, Narrow River, Wide Sky: A Memoir?”

As a memoirist, questions like this and others rattle around when I sit down to write, when I think about writing, when I know there’s something I have to write.

Other writers have said, “I could never hurt my sister by writing about her” and “My family’s too important to me to write about them that way.”

I wrote Narrow River, Wide Sky: A Memoir with an urgency, an ambition, an amorphous goal — to explain something horrifying without vilifying single people, without pointing a finger, without blaming and yet, I wrote hard things about people I love, people who’ll be hurt that I wrote about them, people who’ve hurt other people.

When I first started writing, it was all rants. Preaching. The sermon. The directive. The Answer. Not because I had The Answer, but because I needed to write and at first, I needed to rant. There was something horribly wrong. I needed to articulate it.

I recently told another writer that I’d been writing to prevent the current political situation. She said, “We all have been.”

I wanted to tell all the city girls and liberals and progressives about the evil lurking in the emptier-of-people and vaster landscapes. They said, “Sure, we know. Like if we don’t know, who does?” They were partly right, but they also thought Sandy and Troutdale, Oregon were rural small towns.

I grew up in the mountains on the western slope of the Colorado Rockies Continental Divide where the river ran west and sometimes ran red with heavy metals. My little brother and I had the freedom of wandering two acres. We were small, so it was vast. Above us, mountains rose to glacial heights — mountains of stone and soft meadows of wildflowers and patches of glittering aspen. There were with mines, some abandoned for the gold they failed to continue to produce while others would soon be shut down for the pollution and poison. Dams were built for the sake of a handful of jobs and stopgap measures for providing water to arid landscapes that can’t sustain growing populations. The biggest town we lived in had 800 people in it and was hours from a freeway entrance.

We hunted for arrowheads and other artifacts that didn’t belong to our kin. We gathered behind mythology. We circled around ideals.

It took a long time to learn to write — from writing beautiful sentences, to creating that story arc, to allowing a lack of structure between the lines — the artistic endeavor, to show what I knew as Rural, to find and articulate the metaphors, and to live the stories — the hardest part of memoir.

I’m not a historian or a journalist and I lack an academic literary credential. But I’m compelled to write my story out again and again as reflection and retraction and resurrection, as soulful do-over, as salve and savior. I’m compelled to love the truth, to illustrate, to show not tell. I’m not compelled to vilify individuals. I’m compelled to write us all changed at once.

If, after reading, you still believe I vilified my family members then I failed. I’ll keep writing until my meaning is clear — even to you.

Jenny Forrester has been published in a number of print and online publications, including Seattle’s City Arts Magazine, Nailed Magazine, Hip Mama, The Literary Kitchen, Indiana Review, and Columbia Journal. Her work is included in the Listen to Your Mother anthology published by Putnam. She curates the Unchaste Readers Series.

Jenny Forrester has been published in a number of print and online publications, including Seattle’s City Arts Magazine, Nailed Magazine, Hip Mama, The Literary Kitchen, Indiana Review, and Columbia Journal. Her work is included in the Listen to Your Mother anthology published by Putnam. She curates the Unchaste Readers Series.

Buy the book here.