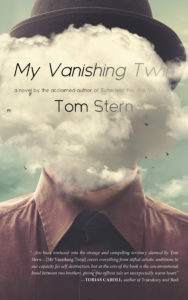

HYPERTEXT MAGAZINE ASKED TOM STERN, AUTHOR OF MY VANISHING TWIN, “WHAT QUESTION DO YOU WISH YOU’D BEEN ASKED ABOUT YOUR WORK?”

By Tom Stern

Tom Stern: Yes, you sir, in front…

Interviewer: Tom, I’d like to ask you the one question you’ve always wanted to be asked about your work.

TS: Oh, you mean, “How do you convey so much brilliance in your work when you’re using the same ol’ everyday words that we all use?”

INT: That’s not a question so much as a vain attempt at prompting flattery.

TS: But in an interrogative form, no less. . . So technically a question.

INT: Point taken, but it is still not the one question you’ve always wanted to be asked about your work.

TS: Oh, really? What do I want to be asked, then, you know-it-all prig?

INT: How does humor get articulated through the written word?

TS: Why the hell would I want to be asked that? I wouldn’t even know where to begin trying to answer such a question.

INT: Isn’t that where all of your writing begins, though? From a place of questioning? My Vanishing Twin, for example, took root when your writing began to cohere around a nebulous and, frankly, profoundly strange concept of a man who is pregnant with his own twin brother, a malformed little person obsessed with getting an MBA. And for months you found yourself perplexedly chipping away at this idea, following the pages as they unfolded in unexpected directions, revising and revising and revising until the story and characters and tone and humor began to cohere into. . .

TS: Aren’t I the one being interviewed here?

INT: Well, sure. But you’re having a conversation with yourself at the moment, so I’m fairly certain you’re splitting hairs.

TS1: I’ll take it from here, then. . . I am fascinated by the idea of humor in writing. Not so much the strand rooted in the tradition of the personal essay, or in stand-up comedians adapting their work for books — although those can be funny, too. But I’m fascinated by the Joseph Heller kind, the Kurt Vonnegut kind, the John Kennedy Toole kind. How humor gets articulated through character and detail and story and tone. I’m blown away by the very notion that we can say that a novel is hysterically funny. In many ways, I think of this type of humor as essentially invisible. It’s like it resides behind or beneath the text. And it surfaces somewhere in between the part of the mind that strings together the narrative and the part of the mind that contemplates and unpacks character motivation. It sparks in the small spaces where your expectation of the alignment of these two elements is thwarted. In the room where you have to stop and re-think for a moment because what you received isn’t what you tacitly anticipated. . .

INT/TS2: We get it, dude. You’re all deep and philosophical. But I would argue that you/I/we don’t approach writing something funny any differently than we approach writing something dramatic.

TS1: That’s because we think that humor is just as dramatic as, well. . .drama. . . But we need another word for drama here. We’re kind of equivocating definitions — if that’s a thing. Is that a thing?

TS2: I get what you mean, anyway. We’re not writing something that is intended to make someone laugh. We’re just trying to get at the essential core of what motivates these characters, rooting it in a truth.

TS1: Yes. And truth in writing is an interesting concept, too. . .

TS2: I’m going to rein you in here: humor. Focus. . .

TS1: Right. Thank you. He often does that for me when we write. Although sometimes he overdoes it, frankly, rather than just giving me the space to work.

TS2: We’re going to die some day, Tom. There’s an argument to be made for efficiency. Unless you want to write one book every 30 years.

TS1: Any more dirty laundry you’d care to air, analytical Tom?

TS2: I’d just like to make sure — in the unlikely event that it is not already retina-searingly clear to everyone — how fanciful and grandiose your philosophical escapades happen to be, intuitive Tom.

TS1: Without them our work would be little more than a helium-filled balloon. Although, I cannot help but pause for a moment to contemplate how perhaps insightful it is that this dialogue is resulting from you asking me a question about our novel in which a man gives birth to his own twin brother only to be driven to re-evaluate his life in light of the unbridled brilliance of the twin.

TS2: Which one of us is supposed to be the brilliant one?

TS1: I mean. . .the fact that you have to ask that. . .

TS2: I can say philosophical things, too!

TS1: Have at it.

TS2: The truth is that our work results from a process that is equal parts intuitive and analytical, and this submerged in a quagmire soup of all the things we are trying to disseminate about our life and our self and the people around us. And humor is just one part of that. It’s a prism, perhaps, through which irreconcilable things nevertheless refuse to be severed simply because they do not seem to sync up logically.

TS1: OK, you will concede that I’m just a lot better at that than you are. “Quagmire soup?” There’s no poetry in how you discuss these concepts. None. It’s like a chemistry textbook.

TS2: And you have never met an idea you didn’t love to obscure, asshole. Case in point, you wanted me to ask you about humor and this is what has resulted.

TS1: Another case in another point, we are precisely where we want to be in that dialogue. It’s meta, sure. But it’s also all here. Humor exists in life and in stories in ways you cannot splice and stain and put under a microscope. But that doesn’t make it any less real. And I think that’s kind of our point. Talking about sex is not the same as having sex. You can describe it all you want, but no understanding of it will ever pin down or replace the spontaneous act of having it — good or bad.

TS2: What does sex have to do with this?

TS1: All part of the “quagmire soup,” analytical Tom.

TS2: I’m never going to live that one down, am I?

TS1: Leave the poetry to me, dude. I’ll leave the crippling self-analysis and critique to you.

TS2: Which one of us gets at the humor, though?

TS1: Well. . .I guess it’s kind of. . .I mean, I like to think it’s more me than you. . .

TS2: Ha! Say it. Go ahead. . .

TS1: Say what?

TS2: Really? You’re going to play dumb with the analytical part of yourself? Like I can’t go all logic-ninja on you? I know that you know. And I know that you know that I know. And I know that. . .

TS1: Fine. If I were pressed to speculate. . . Not that one could ever really know such a thing, but if I were to honestly articulate what feels like a true answer to such a broadly speculative question. . . Not that it necessarily means anything because. . .

TS2: Say it!

TS1: The humor probably arises from the tension between us.

TS2: Ha! You need me, Tom! And you know you need me. In fact, I’m going to go ahead and say it. . . You love me, Tom!

TS1: Well, you love me, too, Tom, so don’t go getting cocky! And, honestly, if you didn’t make me laugh, well. . .

TS2: . . .we would lose our fucking mind.

Tom Stern is the author of the novels My Vanishing Twin and Sutterfeld, You Are Not A Hero, both published by Rare Bird Books. He is also the writer/director of the feature films Half-Dragon Sanchez and This Is A Business. Tom‘s films have played festivals across the United States and in Europe. He holds a BA in Philosophy from Eckerd College and an MFA in Film Production from Chapman University. Tom lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Cheryl, and his daughter, Ramona.

Tom Stern is the author of the novels My Vanishing Twin and Sutterfeld, You Are Not A Hero, both published by Rare Bird Books. He is also the writer/director of the feature films Half-Dragon Sanchez and This Is A Business. Tom‘s films have played festivals across the United States and in Europe. He holds a BA in Philosophy from Eckerd College and an MFA in Film Production from Chapman University. Tom lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Cheryl, and his daughter, Ramona.

Buy the book here.