All of us and none of us were psychic. Natasha in her billowy black dress. Only the prettiest girls could wear such ugly clothes. Lauren with a Nikon slung over her shoulder. She was saving up money to go to Lisbon. Her photo project was on exorcism. We all went to her opening in a tiny gallery, where there was barely room to stand. My claustrophobia wasn’t clinical, but my eye was on the escape route. There was Gail, in her sixties, older than all of us by forty years. She’d frozen her eggs and never used them. She joked we could have them if we wanted. I watched her from my post at the phones, and I thought of those chilled, hopeful cells.

The four of us worked the 9:00 p.m.-3:00 a.m. shift at Beatrice’s Psychic Call Center. It was always midnight. I wasn’t old enough to already have forgotten so much. During those slow and psychic nights, I felt I’d never been anything fixed or solid. Still, all this time later, I don’t recognize the self who appears out of the past and discredits each memory I have.

“Nothing means anything or everything means something,” Lauren said. “Which position would a psychic take?”

“Everything means something,” Gail said.

“Just because you predict something doesn’t make it meaningful,” I said.

We were quiet after that. We were hoping our phones would ring. If the phones didn’t ring, we didn’t make any money. Outside there was heavy mist on the mountains. There was drought and then spouts of El Niño that bombarded us with rain. The fish would be gone by the time my children, if I had them, were my age. I thought of little frozen children walking on dry lake beds. We were told that the world was ending. There were floods and tornadoes; one tornado sucked up a wife when she was on FaceTime with her husband. Technology doesn’t protect you. Just ask the girls who die on cliffs taking photographs of themselves.

“Keep people on the phone,” Natasha said. She’d been here a month longer than me and was fully psychic. “Tell them what they want to hear.” The pep talk was the same each night. None of us cared about manipulating our callers, but around 1:00 a.m., when the phones were silent, and my homework was complete, I started to wonder about my karmic residue, as Lauren called it.

“We’re making it all up,” Lauren said. “If we were really psychic, we’d tell people the shit they don’t want to hear. The deep, dark shit.”

“I’m not making anything up,” Gail said. Gail was a believer.

I was twenty-three. I look back on this time and don’t understand the long, sad emails I wrote to a boy whom I will give the initial C. When I wasn’t writing to him, I flipped through the psychic handbook that summarized our human problems and the human hopes we might ignite in one another with the phrase of our choice.

Suggestions included:

You will come into money. You will find love.

Someone is jealous of you. There is a trip in your future. You are in a time of transition.

You will find good luck in the future.

The best years of your life are ahead of you.

I see a man? No, you’re right . . . a woman. They are important to you.

My callers were the oddballs and outliers. I flipped through my handbook for the abused wife, the pregnant teenager, the girl with a dead mother.

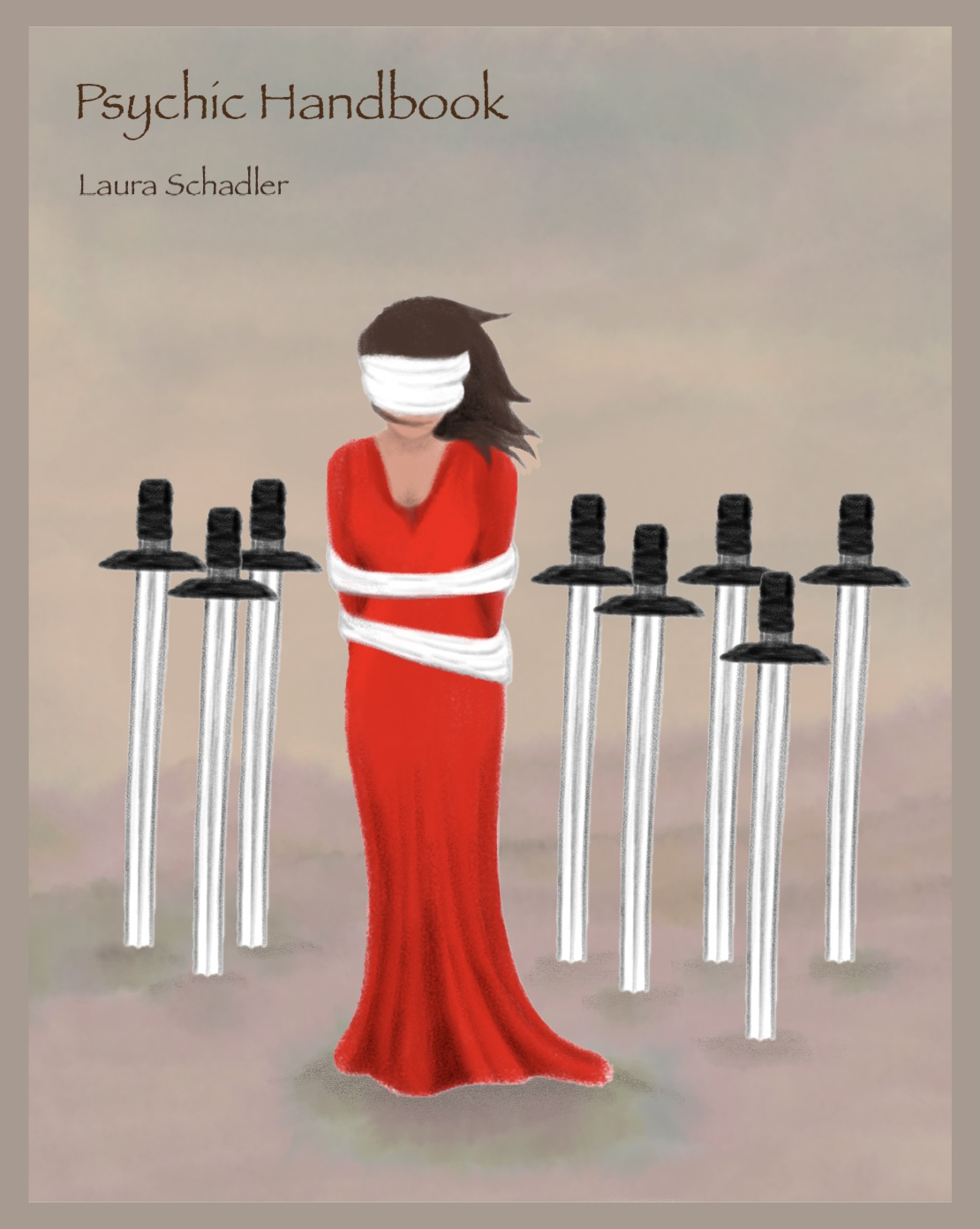

Natasha brought in her tarot deck. We pulled cards, and she told us what they meant. Gail was always getting swords, the men with all the swords stuck in their backs. I tended to pull the major arcana: The World, The Tower, and Death. I wasn’t scared of these clues. I wasn’t scared of much.

It would be a decade before I had to undergo three surgeries for a rare cancer that lived silver and invisible in the organs of my pelvis and abdomen. I would be thirty-five, an inconceivably old age to twenty-three-year-old me. At that age, I understood that bodies ended, but I didn’t really. My body was miraculous. I liked the ways I was soft and chubby. I liked every single way I smelled and every sensation I felt, even the most desperate of hangovers. At that time, I felt so beautiful I didn’t even worry about touching men because I knew they just wanted to touch me. It took a long time to realize I didn’t even know what I desired. I’ve since learned it’s nicer to touch something than it is to be touched, and that there are many ways to inhabit our body.

“Tell me a little bit more so I can get a sense of your vibe,” I said to the woman on the line. This was a stalling mechanism because in those moments people gave away the most revealing details without even knowing it.

“I am having a hysterectomy,” the woman said. “I want to know if I will be okay.”

Everyone’s mom had a hysterectomy when I was a teenager. None of us were properly concerned at the time. The big deal-ness of it dawned on me over the years, as my own organs did tangled things. We only understand other people when terrible things happen to us. The thing about any surgery, routine or rare, is that the ritual of it is something only the body recalls. The outermost parts of ourselves are actually the psychic layer; our skin, not our spirit. That’s one big mistake we make.

I didn’t want to jinx the caller by saying she’d be okay. But I could hardly curse her either. I flipped to the page about stalling for more time in believable ways.

“Something seems to be blocking my reading,” I said. “What?” the woman seemed nervous. “Something bad?”

I looked down at the tarot card I’d pulled earlier. The Page of Wands. “Creative restlessness,” Natasha had said. Gail had pulled the woman sitting at the end of a bed with her face in her hands, the swords all fallen into the mattress. “That’s just another version of freedom,” Natasha promised. I wanted her to be right.

“No!” I almost yelled. “No, being blocked doesn’t mean anything bad. It might mean this is a question better answered by your doctor.” Had this woman ever been twenty-three? Had she ever not taken her uterus for granted? I’d never given mine a second thought even though in that very moment, it might have been deciding to betray me.

“My doctor says it is routine,” the woman said. “I know that on one level, but I can’t help but be scared. There’s complications all the time.”

“There are,” I agreed.

“Do you see one?” the woman asked, alarmed again. I was uncomfortable with my power, so unearned. I never felt so listened to, taken so seriously, as on these evenings when I deserved it least.

“Surgery is nothing to fear,” I said. “It’s the first step toward healing, right?” This line was not in the handbook, just a premonition for her and for myself.

My own advice returned to me years later when I awoke from my surgery with the handsome resident beside my bed in the dim room. His blue scrubs were so pale and yet so bright. We don’t owe ourselves anything, but I was grateful.

That night, after the hysterectomy call, Natasha, Lauren, and I went out for drinks. There was a bar down the street from the call center that stayed open until 4:00 a.m. We drank quickly and quietly for forty-five minutes, tired of talking. People so unconsciously mention love, sadness, hope. We all want the same things, really, and can be so easily convinced of what we deserve.

While I was at the bar, C returned my long, sad email with a short one. Usually I can get over people, he wrote, among some other things. It was a romantic letter, in a way, and I liked it. Imagine being someone that a person could get over. The thing we all forget about romance when we are lost deep inside it is that we will look back perplexed, emerged, as if stumbling from a wood, unable to explain how we got so turned around.

So many of our troubles are so obvious. It’s why the handbook works, the phrases, it’s why they apply to almost anything, to everything, to everyone.

I wrote him back:

You will come into money. You will find love.

Someone is jealous of you. There is a trip in your future. You are in a time of transition.

You will find good luck in the future.

The best years of your life are ahead of you.

I see a man? No, you’re right . . . a woman. They are important to you. Love, B

I thought about the woman’s surgery. What was her surgeon doing tonight? Was he sleeping well? Calling psychic hotlines of his own, wondering about an outcome only mostly in his control? I imagined her uterus, where they would put it once they took it from her. There was something unceremonious about it, taking someone’s insides away from them like that. We are all towers, flames, the swords, and the dark black hood of death himself. I believe it, though, when I say it is all unbearably good.

“What the fuck are you talking about?” C wrote back. “Why are you telling me things like good luck?” I felt psychic looking at his email, maybe for the very first time. We’d know each other for a little bit longer and, after that, not at all. I knew he’d have two sons and I’d have none. He’d live near where he grew up, build houses for a living, and I’d go far away and write books, slim volumes with titles in all-caps black font.

“Most of you are keeping people on the line for an average of fifteen minutes,” Natasha said the next night during her pep talk. “Utilize your handbooks more. There are responses for nearly every single situation. Fifteen should be your minimum amount of time.”

Lauren was out sick. I tried making predictions about what I thought was wrong with her. I imagined her in flames. I saw her on an airplane. I saw her, that camera over her shoulder, on cobblestone streets, by green seawater. I saw her holding the hand of a little ice child walking beside the fish-less sea. I saw C by her side. It turned out that Lauren didn’t come back. She went to Lisbon with what she’d saved so far and a credit card.

Natasha left soon after to start her own divination business. She had people pull tarot cards, and then she told them what they already knew: they had to leave their husband; the decision they faced was difficult; grief splits you open and lets you feel the light; heartbreak is how you feel love; even if it doesn’t get better, it will change.

People rarely called back to tell us if we were right or wrong. I wondered about the caller with the hysterectomy and how it all turned out, as if the way one thing turns out is the true last thing, and nothing else comes after. The last thing that happens isn’t the truest thing. Each part of our life, moment after

moment, was truest truest truest. Long after my own surgeries, I dreamed of her. I dreamed she told me that I was going to be okay. But no one is going to be okay.

You are in a time of transition.

You will find good luck in the future.

The best years of your life are ahead of you.

Six months after my third surgery, at age thirty-eight, I was cured, they said. I tried putting my hands over my stomach and predicting if they were right. I tried being psychic. It didn’t work. Still, I was wiser now than I’d been when I was professionally so. There was a frozen and flamed space where my right ovary had been. My wisdom had no psychic power; it was a wisdom that had no language at all.

Those long, boring nights at the psychic call center comprised so many nights of my young life, the ringing of the phone, that silence on the other end as the person made up their mind to speak, and then the story I listened to, the clues I sought so that I might say something in return. What was the same about this story I was being told, and how was it like all the others I’d heard before?

I listened and I tried to decide whether I could say it to them in a voice they would believe: “You will find good luck in the future. The best years of your life are ahead of you.”

Laura Schadler grew up in the mountains of Virginia and now lives and writes in California. Her fiction has appeared in the Southern Review, the Gettysburg Review, Denver Quarterly, and Slice, among many others. Laura was a MacDowell Fellow and her short story collection was a finalist for the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. She is currently at work on a collection of ghost stories.