By Donna Miscolta

This February marks the thirtieth anniversary of the People Power Revolution that ended the Marcos regime in the Philippines in 1986. That year, from February 22-25, two million Filipino citizens, joined by political, military, and religious groups, occupied Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, a main thoroughfare in Metro Manila. It was a remarkable non-violent revolt in response to the decades of corruption and decadence of a regime that suppressed speech, took over businesses, and embezzled government funds.

It was during the Marcos regime that the Philippine government began shunting off its unemployed from a stagnant economy, most often to the oil-producing countries of the Middle East. When the people forced Marcos from the palace and the country in 1986, little changed under the new democratic leadership for the country’s ruined economy or its practice of sending its workers abroad.

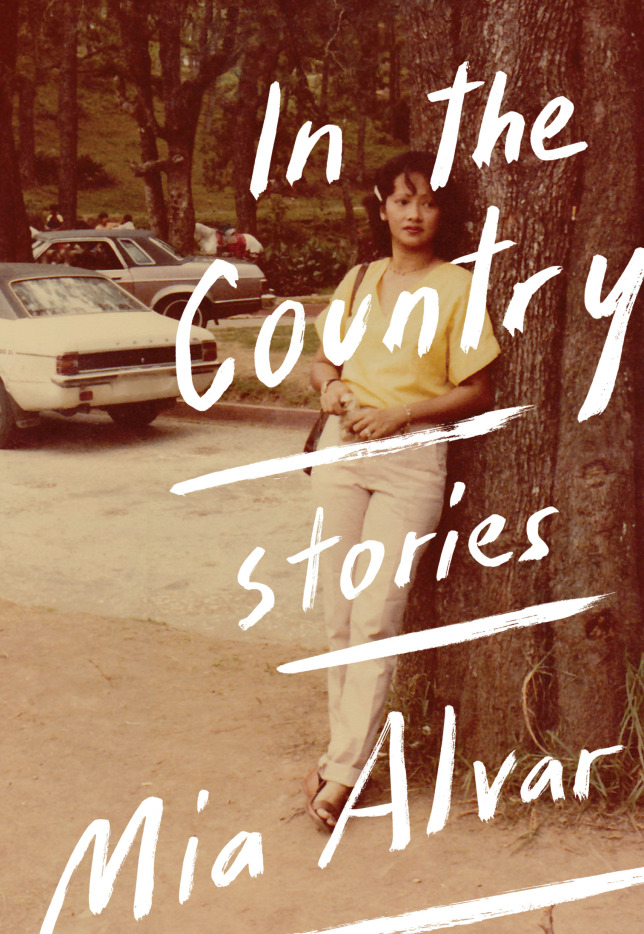

These events and issues form the backdrop of Mia Alvar’s story collection In the Country in which economic inequities and political repressions drive a diaspora of workers and asylum-seekers. In Alvar’s stories, these migrant workers and expats plot their own personal revolts. Sally Rivas in “The Miracle Worker” calls them little mutinies. They’re a repudiation of a role Alvar’s characters are relegated to or have passively assumed. In two stories of Filipinos abroad as foreign workers, Alvar explores the power plays that are, in Sally’s words, meant “to offset some imbalance in the world.”

Sally accepts the job of schooling the disabled daughter of a wealthy Bahrain family, receiving Mrs. Mansour’s gifts while abandoning any pretext of teaching the hopeless child in an attempt to even the scales of power. In her deception, she believes she is making up not only her friend Minnie’s long hours of domestic labor in the Mansour household, but also for her guilt at her own more elevated position as a professional. After her discovery of an even more treacherous little mutiny, Sally grasps where the real power lies, sees that she is after all but a guest worker in a foreign country.

Similarly, in “Shadow Families”, the difference between the professional and worker classes in the community of Filipino workers overseas is an imaginary line, easily crossed. In a foreign worker compound in Bahrain, the educated class from the cities welcome the helper class from the provinces to their homes once a week to eat and sing with them. They pray for them. Sometimes they play matchmaker. The helpers know their roles until Baby comes along. Baby, who dyes her hair and wears high heels, refuses to speak Tagalog, eat Filipino food, or sing karaoke. Baby’s indiscretion, her refusal to be bound by a role, results in her ouster from the country, but not before she permanently upsets the community, the members of which had so carefully cultivated a satellite Philippines in a desert country.

The Filipino community in Bahrain eventually disperses to all parts of the United States, and the narrator laments “… we lay awake in single beds, sensing that we’d snipped a cord not just from home but from the law of gravity itself, and if we tumbled off the planet altogether no one, for a while, might know. Now we were all outcasts, of a certain sort, as well.”

Economic necessity or opportunity is not the only reason behind the diaspora of Filipinos in this collection. In two of the last stories, Alvar’s characters grapple with the political tyranny of their homeland. Just as the characters in the above stories exercise deception or self-deception to tolerate ill-fitting or untenable circumstances, so too do these characters.

In “Old Girl” a politician once imprisoned for his opposition to the Philippine government, is now a lecturer living in the “Manilachusetts” section of Boston. His pet name for his wife is Mommy, though she refers to herself as the old girl, a remnant from her schoolgirl days when the nuns prepared their students to be wives and mothers. The old girl manages her husband’s life, supporting him even in his deluded goal of running a marathon, something for which he has no physical or mental temperament. In his exile he has become inept at the smallest things. On the other hand, the old girl’s management skill is portended on her wedding day.

Speaking of omens, in Manila, at the wedding, they released a dove from its gold cage. It thought better of flying away, alighting on the old girl’s head instead. “Loko mo, that’s a good sign, said her father, as the old girl tried to shoo it off, grateful to have a veil and gloves on. “It means power, victory.”

“Just like we thought,” her mother said. “The groom’s going to be President one day.”

“It landed on the bride’s head,” a niece said. “Doesn’t that mean she’ll be President?”

Everyone laughed, and no one harder than the old girl herself—the quiet, simple bride who’d just dropped out of law school for her MRS degree.

Even though the old girl loves her life in Manilachusetts, her husband insists, “I don’t want to be another sad, ranting, exiled old-timer.” And so they pack their bags, the husband who can no longer deceive himself that giving speeches and pretending to train for a marathon is a life worth living and the wife who can no longer live with the deception that she is merely the old girl. The characters, though never named as such, are fictionalized versions of Corazon and Ninoy Aquino, the latter of whom was assassinated on the tarmac of the Manila airport, the former elected to the presidency in 1986.

The year 1986 is one of the two timeframes in which the final story in the collection unfolds. The other timeframe begins in 1971 and advances through the years of martial law to intersect with the events leading to the ouster of Marcos.

While many of the preceding stories involve characters that have emigrated from the Philippines, the young, strike-leading nurse Milagros makes her stance clear when a young reporter asks whether “given the chance all those nurses would leave City in a heartbeat, for a land of milk and honey? Sidewalks paved with gold or diamonds, depending on whom you ask? The chubby envelopes they could send home?”

Milagros replies, “Your mother gets sick, you don’t leave her for a healthier mother. She’s your mother!”

This leads to a life with Jim Reyes in support of his underground journalistic activities, which she continues after he’s imprisoned by the corrupt, repressive government and for which she pays a spirit-shattering price. The dictator and his wife are never referred to by name, but by the ironic euphemisms Papa and Mama. Euphemisms abound in the country – safe house for prison, disappeared for dead. But finally, the Reyes are done with euphemisms, especially Milagros who surrenders her faith in the country, because it is “still the country that took everything away.”

This last story is easily the most powerful, though each exercises its own muscle in the collection. Whether set in the suburbs of Manila, a small town in the provinces, a foreign worker’s compound in Bahrain, or the Boston enclave of Manilachusetts, Alvar’s stories deliver insight into the issues of immigration, family, community, and country, of how the past intersects with the present, and how the political is often at the root of our little mutinies. How sometimes those little mutinies can result in a larger revolution. How sometimes that larger revolution just spawns more little mutinies.

_______________________________________________________________

Donna Miscolta is the author of the novel When the de la Cruz Family Danced (Signal 8 Press, 2011). Her short story collection Hola and Goodbye won the Doris Bakwin Award for Writing by a Woman and will be published by Carolina Wren Press in November 2016. Find her at donnamiscolta.com.

Donna Miscolta is the author of the novel When the de la Cruz Family Danced (Signal 8 Press, 2011). Her short story collection Hola and Goodbye won the Doris Bakwin Award for Writing by a Woman and will be published by Carolina Wren Press in November 2016. Find her at donnamiscolta.com.