It’s evening at the end of December, in that week between holidays where the days blur together and the wonder of Christmas has faded into the overzealous hype of the new year. Adam and I are driving to Will and Claire’s for their annual party, winding through dark country roads the way city folk do at night: five miles below the speed limit, high-beams on, white-knuckled and tense, ready to slam on the brakes should a bold deer spring across the asphalt. The headlights throw long shadows across the naked trees lining the road, casting stripes of light and dark in the woods. I shouldn’t feel so anxious, on my way to visit old friends.

If a forest at night is haunted, a forest at sunrise is a resurrection. Nothing could get me out of bed in my early twenties like the promise of watching a gray forest turn golden. We’d drive out just before dawn, passing by farmland and eventually plunging into a wooded conservation area. We had rifles over our shoulders by the time it was light enough to see without a flashlight, and then we’d tromp off the trail and find a sturdy tree to settle under, and then we’d wait.

We were merely playing at squirrel hunting; we had no idea what we were doing. We’d had no seasoned hunter to show us the ropes and just took off under the tutelage of Google. We never shot a single animal, but that disappointment was nothing compared to the feeling of watching the world come alive. Bundled under layers in the January chill, our breath misting, we hardly spoke, even at a whisper. I think Will tried more than I did. I looked, sure, searching the treetops for the vertical bouncing of a limb, listening for squirrel chatter or rustling underbrush, but what I remember most is simply being. The Romanticists were onto something: a pleasure in the pathless woods; lovely, dark and deep; the tonic of the wilderness . . . Let your eyes lose focus for half a minute in a forest at sunrise and you’ll blink and find it gilded and breathing, all that life suddenly shaking awake, somehow both silent and deafening.

Inevitably, on the other side of the tree, I’d hear Will stand up. “Nothing’s happening,” he’d say. “Let’s find another spot.”

Reluctantly but faithfully, I’d follow him.

I don’t plan on drinking. It’s been too long since I’ve seen everyone and I want to be sharp, to be aware of them, to preserve every moment. I’m different. I’ve drifted away from them, and they have pushed me further out to sea. I’ve already made peace with that; this last party is just an opportunity to sever it completely, if only in my mind. I’m looking for closure.

But Will offers me a drink, and Adam is following him from the kitchen to the repurposed garage where the bar is. The kitchen is loud and filled with people I have little in common with anymore, so I go with them.

“What’ll you have?” he asks. He has a beard now, something I never expected, and I’m not sure if it’s working. Other than that, he’s the same, from his beer gut to his self-assured swagger to his bright, brilliant laugh.

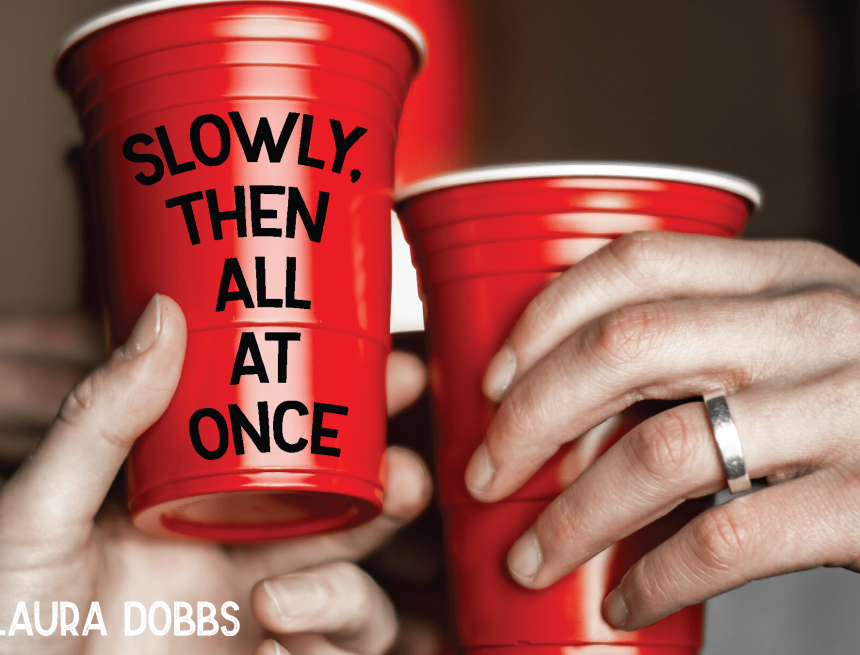

I don’t really want anything, but I ask him for a Tom Collins. He hands it to me in a Solo cup and I wonder if he remembers that he’s the one who taught me to love this drink. I wonder if that’s why I ask for it.

Adam calls for a round of shots, and I envy his ability to shut out the distance and just be present. It’s been so long since I’ve talked to Will that I’m not sure how to anymore, but Adam is carrying on as if no time has passed, and his mood is encouraging. We do a shot of Fireball. Then we do another.

The first time I drink hard liquor, it’s just past midnight on my twenty-first birthday and Will is beside me and a handful of other friends at the bar. We do a shot of something simple and follow it with an Irish Slammer—a shot of Jameson and Baileys dropped into a Guinness and then chugged before it can curdle—and it is the greatest and most overwhelming drink of my life. After, our group snags a corner table and drinks and laughs. I don’t remember what I’m sipping, but I remember feeling the lightness of a buzz, the giddiness bubbling in my chest, and Will saying, “You’re a little drunk,” to which I reply, “I am certainly not.” He just grins.

The following evening, it’s Will who steers my drunk ass away from our dry campus to a party across the street, and who laughs so hard he can’t breathe after an acquaintance gives me a shot that’s half hot sauce and I’m chugging water as tears stream down my cheeks. Later, when the world has taken on a slow-motion haze and I’m swerving around his apartment on unsteady legs, Will gives me the last shot of the night and I throw up in a cooler. He has the decency to lend me a T-shirt so I don’t spill out of my tube top as I’m lying on his couch and calling him every curse word I can think of, because I am certainly dying and it is definitely his fault.

Claire’s roasted a pork shoulder and made vegetables. Will leads us all in a prayer. He keeps it simple and freeform, not the traditional Catholic meal prayer, and I want to believe it’s for my sake. We all make plates in the kitchen and find seats. The table is pretty full, so Will leads a few of our other college friends downstairs where there’s more space, and Adam and I follow. We’re all comfortably warm from the whiskey, and I finally start to relax. I bring up selling Will my hunting bow, which he’s been borrowing for over a year. In my head, this transaction is just another way of detaching myself from him. He says he’ll think about it. There’s five of us, and we play a game of cards, we talk about the newest Star Wars movie, we eat. Adam spills someone’s drink and we all give him shit and the conversation is easy, and yet it’s excruciating.

After a while, everyone trickles back upstairs. Adam and I linger behind. He asks if I’m okay, and I finally acknowledge the lump that’s been sitting in my throat since we arrived. “This is really hard.”

He nods. “I know.”

We’re outsiders now. We’re the couple who left the Church as soon as our wedding was over. Friends we once shared creed and covenant with are now mystified by our newfound progressive ideals. Perhaps more offensive, we are not part of the child-bearing majority. We both know the others pray for our redemption, unable to comprehend that nothing is wrong with us. Adam is not nearly as bothered by this as I am, but we were both surprised to be invited. We’ve been kept at a safe distance for so long. We thought this would be the year they finally let us go.

We rejoin the group upstairs. I alternate nibbling Christmas fudge and vegetables in turn and try to find a place for myself in the conversation. Adam is wasted; I realize I need to either sober up or give in to where this is obviously going. Will and Claire offer their couch; I’m buoyed by the alcohol and too ebullient to refuse. I have always been a happy, relaxed drunk, and tonight is no different, but this is the first time in my life I drink for reasons other than pure fun. Tonight, alcohol is a sedative to ease me through this party, and it is working.

We all naturally separate into smaller groups, and I find myself catching up with my college roommate. It’s mostly painless small talk about work and her kids, and then someone walks in with a bright yellow box: The Catholic Card Game. Yes, this not only exists, but this guy brought it to a Christmas party. Most everyone in the room sits in a circle on the floor to play. Five years ago, I might have, too, giggling in amusement. I observe for a moment as they deal out cards for what is essentially a religious, vanilla version of Cards Against Humanity and then I quietly excuse myself.

In the other room, Will, Adam, and two others are playing a board game that looks much more complicated than any of us is probably capable of in our current stage of inebriation. There are stacks of cards and monochromatic game pieces spread across a complex map. Will’s tone is lighthearted when he teases, “Did you come in here because that got too Catholic for you?”

He isn’t wrong, but I’m startled by how quickly he reads me. I’m not sure what my face does, and I feel like I need to cover for myself, but before I can explain, he reaches out: “You know I love you unconditionally.”

In my head, I answer, “I know.”

Out loud, I retort, “Do you, though?”

It comes up again later. I don’t know what prompts him to say it again— maybe it’s to remind himself. I answer the same way. He waves me off and says, “We’ll talk later.” My heart swells with hope even as I mentally recoil. After all this time, I want his approval yet am afraid of the requisite vulnerability. But I know it doesn’t matter; that conversation will never come.

We’re sitting in the lounge at the Catholic Newman Center. Will’s softly strumming a guitar. I’m typing an essay. It’s evening, and as usual we’re two of the last to leave. This place is a home to us; we spend more time here than our dorms.

I ask him, not for the first time, large, sweeping questions about the nature of God, the universe, life. He seems so much wiser than me, more knowledgeable on matters of faith and the world, and I am nineteen and fatherless and so hungry for someone to guide me. He sets the guitar down and gives me all his attention, and I feel safe and acknowledged and accepted as I hand him my doubts and my fears. He has an answer for each of them; he’s a good speaker and has a gentle strength that can put anyone at ease, and it’s so easy to forget that he’s young himself, that he doesn’t know everything, that I have no real reason to put so much trust in him. Because this is in part a performance for him. He loves to captivate an audience. I am too close to him to realize his frail ego craves adulation. It will be years before I recognize that this relationship is more parasitic than symbiotic.

But then, at nineteen, our friendship feels like destiny. We’re inseparable for the better part of a decade. It’s rare to see one of us without the other. Our friendship is late-night Taco Bell runs and early-morning workouts. It’s road trips to catch a rugby game, it’s summers spent driving around listening to the same 10 CDs, it’s college town bars and church retreats and playing guitar and video games and going to MMA fights. It’s deep conversations and inside jokes and being in each other’s weddings, and at the heart of it is laughter and a deep, abiding fraternal love.

The evening’s events begin to run together. Adam wins the game and falls in a heap on the floor in victory. We pull out another one and my team loses miserably, though I’m too drunk and giggly to care. At some point, Will must make a comment about fighting because I boldly declare, “I could take any one of you, no contest.” He rolls his eyes and tells me I’m wrong. I challenge him. Neither of us is in any condition to fight and I have never felt the need to prove myself in this way, especially to him. But there is a hurt that is buried beneath so many years of denial, and even with the alcohol softening the sting, I realize I want to hit him.

We go outside. He’s saying something, and I think, Is this really happening? and when I step my right leg back into a fighter stance and raise my fists, he mirrors me. Then he drops his hands and says, as if it should be obvious: “No, Laura, I’m not going to fight you, come here,” and embraces me, laughing.

I think a physical fight would be simpler.

Will is the first person to punch me in the face. Of course he is. It’s open mat at our MMA club and I ask to try boxing. I’m cautiously circling him, barely moving forward at all, when the leather of his glove connects solidly with my jaw. I stagger backward, stunned, but then a switch flips; I throw myself at him with a mad determination and manage to land a blow before someone calls time. He beams, proud behind a fat lip. I am hooked, instantly.

Later, bruised and aching yet tingling with an electric aliveness, I say, “That was the most invigorating thing I’ve ever done. I’ve never played a sport before. Where did this come from?”

He answers, “It was probably always there. You just never had a chance to find out before. And now it’s like you’re finally awake.”

The rest of the night is a blur. Another game, more drinks, me drunkenly leaning on Will’s shoulder and him shaking me off in brotherly annoyance. At one point, I tell him, “You know what? You can just keep the bow.” He agrees to give me some of whatever he ultimately kills with it. I call it a deal. It feels like letting go.

Our other friends depart until it’s just the four of us—Will and Claire and Adam and me. We’re sitting at the kitchen table and we’re just talking. My entire face is numb, my vision is blurry. It’s past midnight and we should be going to bed; Adam is subtly trying to suggest this, but I’m fighting it. Everything will be different in the morning and I’m not ready to say goodbye. But eventually Claire sets up the pull-out couch in the basement for us, Will gives me a T-shirt to sleep in, and the night comes to a close.

It happens slowly, by degrees, and then all at once.

We graduate college, get married, settle down. No longer surrounded by a like-minded community, I realize my mind is not so alike. I wake up and find my own beliefs. I make a conscious choice to break away and I’m met with no resistance. No one tries to re-evangelize me. No one tries to coax me back into the flock.

In fact, there is nothing at all. I’m kept at arm’s length. Birthdays pass without acknowledgment, the usual traditions come and go without invitation, people come back in town and forget to stop by.

For a while, we still have the gym, and hunting, and music and games. As long as we can share hobbies, we have something to talk about, even if our souls no longer strain for the same sort of freedom. Then the children come, time portioned out more carefully in an ever-shrinking ration.

And then, suddenly, I’m an afterthought, reserved for an annual gathering of which I am a shameful minority. We never talk about it. We never fight about it. What’s left is a scattershot collection of reunions and piecemeal attempts to break through the fog of what we can’t say.

In the morning, Adam and I silently gather our things, leave a note, and are gone before seven. I’m so hungover I want to be dead.

A dense fog hangs over the property. We drive even more cautiously than we did on our way in; what we’d expected to be easier in daylight is trickier now, as we can’t see more than two or three feet beyond the windshield. My brain is muddled through the haze of too much booze and too little sleep and I’m not sad, not yet, though there will be moments in the days and weeks and years to come when I will be.

There’s no ritual to mark when a friendship ends. It isn’t a death or divorce: there’s no funeral to attend, no documents to sign. It’s simply the slow fading of a photograph in the sunlight, the progressive erosion of a once resplendent monument, the undetectable evolution of one form into another. After, there is only a lifetime of crucial moments that appear painfully and unexpectedly as if to say: That was how we were. Why couldn’t it have been enough?

Laura Dobbs is a high school English teacher in St. Louis. Her poetry has appeared in Snapdragon: A Journal of Art and Healing and has won second place in The Wednesday Club of St. Louis’ Original Poetry Contest. She studied English with an emphasis in creative writing at Truman State University and later earned an MA in English at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.