by Christine Maul Rice

I first heard Patricia Ann McNair read at Martyrs on Lincoln. Or was it the Hopleaf? Or, perhaps it was…no matter. The point here is that McNair headlined many reading series, shared many stories, wholly imagined or otherwise. Memory, we’ll all agree, is a slippery thing and these details are best debated at a later date. What’s important here, what I vividly recall, is the feeling that shook me when, at this particular reading, McNair delivered her closing line to the standing-room-only crowd and everyone gasps. It’s a punch to the gut, this ending line. We feel it viscerally—the rhythm, tone, emotion, word choice—it’s all humming. We recognize craft, yes, but it’s more than that: It’s a physical tremor that moves through the audience, fleeting but nevertheless there, the one you get when an artist performs a piece with tenderness and abandon and power and you are living it so that, even when it ends, you sit there, waiting for the next word.

You know that feeling, right?

Regardless, McNair hits that line and a beat passes while we let the tremor pass and then the place erupts. Standing room only, remember, and even McNair seems a little overwhelmed at the response because she blinks at the uproar before thanking the crowd and exiting the stage.

That’s my first memory of hearing McNair read. Maybe we were elbow to elbow waiting for the applause to end?

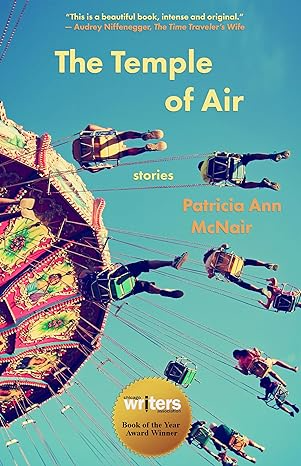

In lieu of a McNair live performance, you have the opportunity to experience the next best thing or, in truth, the first best thing: Tortoise Books’s reboot of The Temple of Air. For those of us who love the feel of a book in our hands, that is the very best thing.

Since 2010, McNair’s byline has appeared at least a dozen times in this magazine. Looking back over her work in Hypertext, I’m reminded of McNair’s range as a writer. Her essays have tackled the horrors (multiple) of the former guy, silence, beauty, boredom, her teenage years, her father’s death, her relationship with her mother and brother Roger the Dodger, among other topics. In her essay collection, And These Are the Good Times, McNair’s writing is marked by an honest vulnerability. She’s writing into the discovery instead of writing to a predetermined end. She’s on a quest, a personal journey, always a personal journey, stepping back to take in the landscape where those hard-to-pin-down universal truths reside.

Maybe that’s why her essays and fiction are among the most visited pieces on the site. McNair and I caught up to discuss power dynamics, well-drawn characters, how a collection takes shape, stories that make me weep, and (lucky for us) the re-publication of her glorious collection, The Temple of Air.

CMR: Rereading the collection and experiencing the three new stories for the first time, I kept thinking about your deft use of power dynamics. In the new story, “This and Other Miracles,” you fully explore one of the original characters, Maddie (the mother in the titular story “The Temple of Air”) as a teenager. You also flesh out the town Sheriff, Manuel, and Edith. These characters react out of their vulnerability in the face of power.

What drew you to those characters? To their stories?

PMc: I am taken with this idea of power dynamics shifting, Chris. When I first started writing, I am not certain I understood that characters I wanted to make real on the page had to be able to shift in their positions much. As a reader, though, I have always admired the nuances of well-drawn characters. How did Ann Petry make me ache for her character Johnson in “Like a Winding Sheet,” and then make me hate him, and then make me ache some more? How did Dostoevsky get me to almost understand and empathize with the very flawed thinking of Raskolnikov as he plans to murder his landlady in Crime And Punishment? It must have been the humanity these writers found in their characters, the ever-shifting good and bad we all carry with us, whether we want to admit it or not. And as our characters shift in their goodness, their badness, the way others react to them must evolve, too, the dynamics of their relationships teeter and totter.

The main characters in the new stories were very small characters in the original collection; I didn’t even name some of them. Maybe that’s why I gave them space in these stories, allowed them their take on things. I don’t think I would be far off if I said that in the original stories, they were types more than people. I wanted them to be people, humans. And so I looked for their humanity and tried to plumb that. If they were ineffective in certain situations, how might that affect the story? If they were in control of things, what then? What more did these characters want, and how would getting it (or not) tilt the scales of their relationships? These kinds of questions and trying to answer them on the page through characters, their internal points of view, and their interactions with other characters excited me when I thought about writing new stories. And it excited me to ask these questions of characters I may have shortchanged in the first edition of The Temple of Air.

In his memoirs, Sherwood Anderson wrote:

The stories belonged together. I felt that, taken together, they made something like a novel, a complete story… I have even sometimes thought that the novel form does not fit an American writer… What is wanted is a new looseness; and in Winesburg I had made it my own form. There were individual tales but all about lives in some way connected… Life is a loose, flowing thing.

I love that line: “Life is a loose, flowing thing.” There are many parallels between this collection’s overall structure and Winesburg, Ohio. Can you talk about the way the stories originally came together in this collection and how the three new stories emerged and fit in?

It sometimes surprises me how few stories I ended up with in the original publication; I’d written a number of others that didn’t make it in the cut because they were not successful stories on their own; they didn’t stand up.

Why is that? Perhaps because the stories that did survive—for the most part—were written as stories first, collected later. And when I initially put a bunch of them together, I tried to write the missing parts, too, tried to be very chronological about it, tried to answer whatever questions folks might have from one story to the next.

I wasn’t up to that task, though. This isn’t a novel, not even a novel in stories. It is a collection of linked stories. Moments highlighted from a number of lives connected by place, mostly, but also by circumstance and history. What Sherwood Anderson says about life—calling it a “loose, flowing thing”—helps me understand more about this book. These are the moments that take my attention—you know this principle, Chris, from our teaching together in Story Workshop classes; we always coach our students to look for what is taking their attention most strongly.

And still, I think I needed to write the other stories to know more about the ones that survived, to know more about the collection as a whole. Like starting with a huge block of granite and chipping away until the real thing, the thing I am trying to make, (or maybe more accurately, the thing it wanted to be) appears.

When I gathered the stories together, though, I still had to make choices and changes. Most of the stories were published previously, but in the book they might have changed point-of-view or character names here and there. I wanted to get a sense of a broad range of ways of telling, and I wanted to pull some threads through from one story to the next. That was a lot of putting it all in one place, looking at the book as a single thing instead of as a bunch of parts, and working toward a certain unity of purpose.

And I had some rules for the new stories. They had to do all of those things above. I suppose I wanted them to work apart from the others, and as a part of the others. I also knew I wanted to make more use of male characters, and not just as seen through the lens of my female characters. That’s where Sheriff comes in, where Manuel does. And I looked for ways to fill in the timeline of things. Not as a way of supporting a chronology, but as a way to look at how a place can change (or not) over time, and how people’s lives and attitudes there can as well. I hope these new stories tell more about this place New Hope, and about the way things have evolved over time. And in doing so, shine new light on the stories and characters I published originally.

Anderson also said, “There are no plot stories in life.” With linked-story collections, like The Temple of Air, the “loose and flowing” narrative is, for me, wonderful to experience. As I reread each story (and read the new stories), I asked myself: Where have I met this character before? And then I would page through the book to figure it out. It was like fitting together a wonderful puzzle.

I have never really considered plot very much, and for a long time had some disdain for the idea of it. So it surprised me when Donna Seaman, in a review of the book in Booklist, said that the collection was “strongly plotted.”

The contemporary novel has become so many different things, and some of the old rules about plot and structure are being challenged. That is very exciting to me. Still, in my mind what makes a book successful in its creation is when it finds a certain wholeness. Sometimes that comes from plot. Sometimes that comes from a different sort of knowledge, like in Winesburg, Ohio. Life is plot-less even as it has structure: you know, beginning, middle and end. But plot or no plot, traditional structure or something experimental, books should bring the reader to a deeper awareness of what it is to be human, to be lonely, to grow, to despair, to exist. In thoughtful books, in well-written stories, there are questions raised and one thing causes something else to happen. Is that plot? Perhaps somewhat. At the very least, these things—the questions posed, the stakes, the physics of events and actions tumbling into one another—lure the reader along from page to page.

When I first read the collection, back in 2011, I remember mourning when I’d finished the last page. I felt that hollowness I get after closing a book I thoroughly enjoyed. The stories are crafted so beautifully.

For the original collection, the writing took over a decade. Can you talk about that process? And how did it feel to let go of characters you’d held on to for that length of time?

I think one reason why these stories took so long was because I kept revisiting the characters: Nova and Sky, Michael and Annie, Hoof, Christie, and some of the others. Once they appeared in a couple of the stories, I wanted to learn more about them, write them out. In some cases the stories weren’t originally meant to be recurring characters, but it started to become clear to me that they had to be—the man in “Running” was too similar to the man in “The Things That’ll Keep You Alive” not to be the same guy. They even looked the same to me when I imagined them. The same with Sky. I kept creating this type of character, a sort of dangerously charming, long-haired blond guy with green-blue eyes that my girl and women characters were attracted to. So of course he had to be just one guy: Sky.

But you asked something else—about how it felt to let go of the characters. Frankly, I haven’t entirely. That’s why I was so pleased when Tortoise Books wanted to reissue the collection. It gave me the opportunity to revisit some of the characters again. Not just in rereading and preparing the manuscript for publication, but by writing some brand new stories with some of that recurring cast. One thing that is interesting to me about the new stories is how my focus has shifted in the years since the original publication. I always thought I would tell more about the young characters—particularly about the teen-aged girl characters. (I love that time of life—we are young enough to not know everything, yet guileless enough to think we might.) But as new stories opened up for me, it was the older characters who wanted my attention. Perhaps that has something to do with my own advancing age.

Also, I had been working on a novel set in New Hope, the same fictional small town, and despite not being able to get the novel quite right, I found myself exploring some of those “old” characters’ lives once again, particularly as they rubbed up against new ones. I mined that material some for the new content of this edition. There are small-town issues I grappled with in the failed novel that weren’t in the original stories. Migrant workers and bigotry for example. Even though I was willing to let the novel go (for now? forever?) I wasn’t willing to let go of those topics. The new stories let me dig in again.

These stories never turn away from the moment of dramatic tension—no matter how difficult. No cliché endings here. Were you ever tempted to let your characters off the hook?

I am not sure I could do that even if I wanted to. Why is that, do you suppose? I am not an unkind person; I like folks to be happy. But I am drawn to stories that are bittersweet at best, or the ones that make you ache. I remember reading Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love when I was an undergraduate, and it blew my mind. Not so much the minimalism—exaggerated by his editor at the time—but by the fact these stories did not end happily. I don’t think I fully understood that was possible before that. And while I have had a happy, lucky life for the most part, the moments that probably shape me most as a writer are the small heartbreaks: my brother’s face when we were told my dad died; being picked on by the neighborhood bully; being lonely in a relationship. And I don’t know if this is going to make any sense, but when I remember those experiences I feel honored to have witnessed them. As a reader, I feel some of the same privilege to be trusted with these moments and to be able to read them on the page.

All of that said, I was eager to find moments of hope in the town called New Hope. I hope I’ve done that.

In the opening story, a baby falls out of a carnival ride. It’s a wrenching event that touches the entire town of New Hope. Here’s our first taste of tragedy—not buildings blowing up or car chases ending in mangled steel. The tragedies aren’t only in the physical world. Tragedy scrambles your characters’ internal worlds too.

While I was pulled to an event that the whole town would be able to witness and be stunned by as my opening, it was important to me to make that thing (and some of the other tragedies) horrifying, yet believable. Dare I say familiar? Or at least not too far out of the scope of everyday, ordinary life. But the worst of what folks experienced had to be internal, you know? Like loneliness and crises of faith and culpability and grief. To me, those personal devastations and quiet desperations are more interesting than the fictionalizing of blowing up buildings. I wanted the feeling a reader might carry away from my stories—the loss she might feel from what happens in the first story; the sadness instilled on a small town in a time of war; the disappointment a teenager feels when betrayed by the adults around her; those sorts of things—I wanted those emotions to stick with a reader. Not the manufactured pyrotechnics of destruction.

Your writing is lush. Can I use that word?

Lush is a good word if you mean lush like thick and fertile and dense and green. If you mean drunken, well…but maybe that’s okay, too. Sort of swirling and rambling. I think the writing swirls and rambles, too. But—I hope—in a good way.

In a very good way. Even “dickhead” and “motherfucker” sound amazing wrapped in your prose. It all seems to work together. How is that possible?

Wow. That’s about the nicest thing anyone has ever said about my writing. I’m going to take this question seriously, because I think you mean it seriously. Those places where words like “dickhead” and “motherfucker” hit the page are entirely in a character’s voice, and I like to think that maybe readers have developed some sort of affinity for the character, even if she or he isn’t all that likable at first. So if there’s compassion, there can be acceptance—or tolerance, at least. Beyond that, though, I am really interested in the rhythms of language, and I think that helps those words fit, too. Are you a fan at all of David Mamet’s plays? I am, and I think his dialogue is very poetic. Complete with all the bad language. It’s a rhythm thing there, too, partly. Some anti-swearing folks think that “creative cursing”—you know, highly euphemistic, indirect, and highly elevated language—is more cerebral, more artful than plain cuss words. Not me. And I love to let sentences wind out and out; love to catch the precise metaphors, too. So maybe that is part of what you are referring to when you say such nice things about the language.

There are a few motifs running through the book: hands, air, faith. Those things that can slip and morph. How do those connect the stories?

PMc: Some of those motifs are part of my own everyday makeup. For some reason I am fascinated by hands. I still remember what my dad’s hands looked like, what they felt like. He had these sort of paws. He patted us like we were his cubs. My mom was a fidgeter. Her hands were like mine. Sort of bony and veiny and always moving. We had a baby-sitter when I was a little girl who had the softest hands in the world. I can still feel her fingers on the back of my neck when she put my hair in a ponytail. So hands are a detail I notice, make note of, often put in my writing. In this case, they became even more important, what we hold onto, what we drop, etc.

Faith—the religious kind—is the same for me. I don’t understand it in any way. I come from a very non-faith-based upbringing, despite my parents having been the children of churchgoers, my mom a missionaries’ kid. So why we believe what we believe or don’t is fascinating to me. It all became a big puzzle for me when I was the age of some of my characters and when my father—an atheist—died.

Air turned out to be a good connection to faith for me here. What we need, what moves things, what we can’t see around us, what howls, what caresses.

This answer so far makes my choices sound far more deliberate than they actually were. I think the writer’s mind does a lot of this work on its own, in the subconscious. And eventually, if we work at it enough, listen to what the story is saying, what the words might mean, we can start to see the connections, the repetitions, the patterns of meaning and motif and discovery. I wrote some stories that had similar things I attended to—hands, air, faith, my own current concerns and obsessions—and the patterns presented themselves after a while, and then I pushed the patterns.

If I had started to push before the patterns revealed themselves, if I’d had a plan for the connections I wanted to exploit, it would have been a disaster. So intentional. So manipulated. I am not smart or talented enough to execute such a deliberate plan.

“The Way It Really Went” made me weep. It reminded me how we think we know what’s going on with another person but, most of the time, we’re just completely off and how people grow distant right under the same roof. And forgiveness. It’s mostly first-person from the wife but, for some reason, I think of the narrative coming right from Jim. How did you get that sense of Jim so strongly on the page in a first-person telling from Annie’s POV?

Thanks for crying, Chris. My goal is to make everyone cry at some point. It is a very cathartic thing, crying. (I might be kidding here. Might be.)

But your question is about point of view. The story began as Jim’s story in early drafts. I spent most of my time close to him. It wasn’t until I wanted to see what Annie had to say for herself that it switched to first person. So maybe that is part of why Jim still seems present even when he isn’t telling the whole story.

That said, the opening is in second person, a thinly veiled first person POV of Jim. We start the story nearest to his perspective, are lured in by his dawning awareness that his life is not what it seems, that he may be in some real trouble health-wise. And then we find out from Annie how the rest of his life has become something other than great.

If you read the book in order, starting with the first story and moving forward, you also get to know Jim’s despair in “Something Like Faith.” He is actively involved in the events of the book from the beginning, so I hope readers will come to care for him, understand him, recognize him in the stories that follow. (And an aside: you don’t have to read the book in order…I mean for the stories to stand alone, too.)

I have one more question: Two of the new stories investigate original characters as older adults. In “Gracias,” for example, we see Edith as an elderly woman, a woman struggling to navigate the world in a body she barely recognizes, a woman coming to terms with the harsh realities of her life, memories she can’t quite square. Why did Edith take your attention on the page?

Edith is the mother of two of my younger characters, Nova and Sky. When I first wrote her, she was absolutely in service to them, to their stories. Frankly, she was a little flat. She was unquestioningly religious, abandoned (but uncomplainingly) by her children’s father. Nova, the character who holds the first story’s point of view, would say Edith was small-minded. Perhaps because she could not see the full complexity of Edith, her mother. Perhaps she wasn’t looking for it.

I, however, found myself looking for it. She was religious, but what if she were an obvious sinner? Edith is a shoplifter. A liar. She holds her son Sky on a pedestal, ignores his solipsism, his dishonesty, his acts of violence. This imagined son helps her fill the holes in her soul.

An aunt of mine was a very faithful person for most of her life. However, in her last decades, her faith was challenged by everyday things—loss, loneliness, disappointment—and so she gave up on God. What if this were Edith’s story, too?

I also wanted to explore how people might come to recognize someone different from them, someone they might perceive as threatening, as a stereotype, as a human worthy of friendship, consideration, and care. The connection in “Gracias” between Edith and Manuel helped me to do that, from—as the current cliché goes—both sides.

Finally, the aging Edith was interesting to me because I am aging. The creaks and pains in her body, the slippery memory, the need for company and kindness, these concerns (my concerns) have made her real to me. And I hope they make her real to the readers of this new edition of The Temple of Air.

Patricia Ann McNair has lived 95 percent of her life in the Midwest. She’s managed a gas station, served as a medical volunteer in Honduras, sold pots and pans door to door, tended bar and breaded mushrooms, worked on the trading floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and taught aerobics. McNair’s work has appeared in various anthologies, magazines, and journals including American Fiction: Best Unpublished Short Stories by Emerging Writers, The Rumpus, Barrelhouse, The Nervous Breakdown, Superstition Review, LitHub, Hypertext, River Teeth, Fourth Genre, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, and others. She’s received numerous Illinois Arts Council Awards, the Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year, Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award, and a Finalist Award for Prose from the Society of Midland Authors. An Associate Professor Emerita of Creative Writing at Columbia College Chicago, McNair facilitates adult writing workshops and is the Artistic Director of Interlochen College of Creative Arts’ Writers Retreat. She lives in Tucson with her husband, visual artist Philip Hartigan, and a yard visited by feral cats.

Christine Maul Rice’s award-winning novel, Swarm Theory, was called “a gripping work of Midwest Gothic” by Michigan Public Radio and earned an Independent Publisher Book Award, a National Indie Excellence Award, a Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year award (finalist), and was included in PANK’s Best Books of 2016 and Powell’s Books Midyear Roundup: The Best Books of 2016 So Far. In 2019, Christine was included in New City’s Lit 50: Who Really Books in Chicago and named One of 30 Writers to Watch by Chicago’s Guild Complex. Most recently, her short stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Allium, 2020: The Year of the Asterisk*, Make Literary Magazine, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, The Millions, Roanoke Review, The Literary Review, among others. Christine is the founder and editor of the literary nonprofit Hypertext Magazine & Studio and is an Assistant Professor of English at Valparaiso University.