By Emily Hipchen

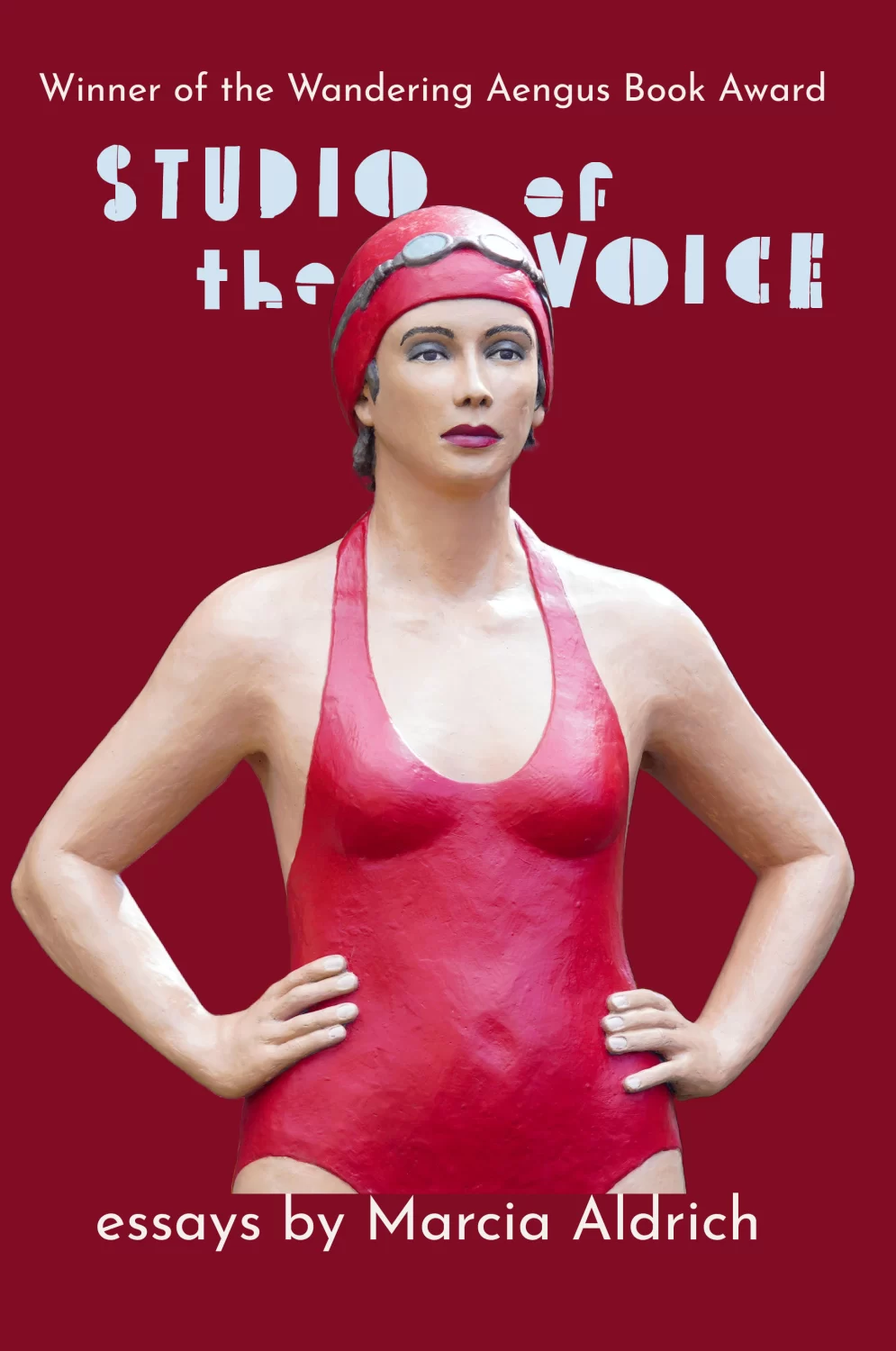

Marcia Aldrich and I met when she was the editor of Fourth Genre and published an essay I wrote about my experiences in India on my Fulbright. Afterward, I used Marcia’s award-winning Companion to an Untold Story in a course on life-writing, where students were fascinated particularly by its unusual structure, but also by its brave engagement with a difficult subject, her friend’s suicide. Marcia’s insights into the composition and content of that text were deeply helpful to students (and to me, who was just learning nonfiction myself). We connected on social media afterward, and earlier this year, she contacted me there and asked if I would be interested in talking with her about her new book, Studio of the Voice. Of course I would.

Emily Hipchen: I want to start with form, a quality of your writing that is distinctive and I think an area of play in your writing. In reading Studio of the Voice, I thought often about spaces/spacing/space—the way it manifests in setting, as with the space of the bed and between the bed, the face as a space kitted out with furniture, the space of a dress, of a pool or the lake, the space of a diagrammed sentence, that inside and outside a purse (a jail of a bag!), the space that is temporal between what was and what is (and what is to come), even the spaces in other people’s lives or between or not between other people’s lives, as with yours and your daughter’s, yours and Greta Garbo’s, your mother’s and Ingrid Bergman’s.

Marcia Aldrich: Space in my writing is not just information or backdrop or setting. For example, in my first book, Girl Rearing, the first sentence is: “I was born in an alley.” The alley is constitutive, defining, an active significant element in the puzzle of the story of girl rearing. Lyn Hejinian, who just died and was an early influence, said, “To some extent, each sentence has to be the whole story.” Many of the sentences in Studio of the Voice—including the diagrammed sentence, “When I swim the sidestroke, I become my mother”—are synecdochic for the larger story of my life. Metaphor is required to get at and convey the elusive life lived. The alley, its poetics of space, was where my story began. The sidestroke with its two words, two entities, was the conjoined space for what felt like an inevitable merging of identities.

EH: The idea of the sidestroke as a space of conjoining and difference (you and your mother) is lovely, especially this idea of the stroke, which is at least for British speakers a mark of punctuation that both connects and divides. Do you mean to collapse the boundaries between the spaces you describe or inhabit, or do you mean insist on them?

MA: My son once said to me, as I drifted, irresolute, along the racks of bottles in a wine shop, “Remember that you are smarter than the wine.” In this case, however, I think the book is smarter than the writer. Whatever might seem intentional usually isn’t—it doesn’t work at a conscious intentional level. I’m able to be more scholarly and interpretive of other writing, but not my own.

EH: Turning off the critical voice at the moment of creation is crucial. I think if we think too much about the process in the process of doing it, we would never do it.

MA: I began as a poet and a scholar of poetry, oriented to the objective correlative. Early on I was encouraged to find the adequate detail that would best carry the poem. It is instinctive for me to dream my essays, to see them cinematically, spatially. In “The Structure of Trouble,” I describe my mother’s retreat in the late afternoon to her bedroom, where she would often disappear to avoid her duty, making the all-important dinner: “Down the beige hall to her bedroom she’d pad, trouble incarnate, and then she’d close her door.” Later in the essay when my father comes home to find my mother lying down again, he eventually turns to me, as a female substitute to my mother, and asks: Will dinner be ready any time soon? After preparing something you’d in an act of generosity call dinner, I follow my mother in her collapse and emotional retreat: “I padded heavily down the same beige hallway as my mother, trouble incarnate, following her foot impressions in the plush pile.” These are but two examples wherein the spaces between my mother and me have collapsed and I have become my mother, whether I wish to or not. The forces of the gender identification are so great that I follow her, though in this second instance I clearly wish for another story than the one I’m in. How to feel about the merging of identities in “Sidestroke” is open ended: Is it a tragedy? A comedy? In the battle of wills between mother and daughter, who wins, and what does winning mean?

In my last example, from the first section, “The Stronger One,” a title that highlights the contested terrain of the book, I describe the drama between me and my daughter as a field of tension. “She and I are fields of force, pushing and pulling against each other across its space. The viewer’s eye is drawn first to the daughter, who strives toward the cross street at the end of the alley, her head flung back to see how she is pursued, and then to the mother, lunging out of the backyard gate in the darkening alley, her stricken face in profile, a Gothic convergence of weights and strains upon a slender pier.” Here in this instance, there is no collapse of the distance between mother and daughter, the space at the heart of their bond.

EH: The pain in that bond is so clear in that essay, and the difficulty of maintaining both closeness and the integrity of selfhood. Elsewhere you notice pain in writing about family, not just pain in recollection, but pain in the act of exposure or contemplation of someone else that the writing requires. There is a delicate balance in these essays of accusation and explanation—even forgiveness for giving pain—particularly in your portrait of your mother, sometimes of your father, almost never of yourself.

MA: Do you find it’s a hard thing to step back into what you wrote, especially if it is painful material? I think of Cheryl Strayed speaking around the world about the death of her mother and her grief. How did she do it? I don’t have those compartmentalization skills.

EH: For me, the pain of the re-reading isn’t revisiting the memory but about knowing—seeing how—it could have been done better. I don’t feel the pain of the moment I’m describing, no; I feel sometimes a longing to be back in moments I describe that were good ones or ones I didn’t know were good and I wish I had known that at the time. The painful parts seem, in writing, like they happened to someone else. Maybe that’s what I’m doing, writing them—creating necessary distance so I can remember them.

MA: Once I was on an Associated Writing Programs conference panel in Boston titled “How to Lose Friends and Alienate Loved Ones: Exploitation vs. Documentation in Creative Nonfiction.” There is an unavoidable transgression in writing about other people in nonfiction. There’s no getting around the inconvenient fact that some people won’t like being written about. They won’t understand and they’re likely to feel betrayed. It isn’t as if you’re writing about a bunch of trees or sunsets, nor making splatters of paint on a canvas or notes ascending on a musical scale. I often feel the way Gertrude Stein did. She said, “I write for strangers and myself.” My writing is not about settling scores or retaliation or cathartic expiation. It’s about making something beautiful out of the struggle with human imperfections and mystery.

After the panel I mentioned, I walked to the Museum of Fine Arts and found myself in front of Andy Warhol’s Oxidation Painting, from a series referred to as the Piss Paintings. Warhol spread the canvases on the floor, applied copper paint and, while it was still wet, invited certain intimate friends to urinate on them. The aesthetic presented was achieved through the application of bodily fluid, a waste product, urine, and this bringing the body literally to bear on paint to create art has received a divided reaction, the same reaction memoirs and personal essays sometimes receive. It saddens me to think how poorly creative nonfiction is still understood, as a lesser art, a defilement or transgression—as piss art. Maybe writers do something more than, in Joan Didion’s words, sell someone out. Sometimes writers bear witness, they honor the complexity and contradictions of living, they give of themselves, the blood and the waste. Sometimes piss art is good art.

I’ll say what other writers have often said: once you cast your memories into words on the page, those memories take on another status. Like it or not, language mediates and transforms memory. The written version writes over, dramatically so, the original, if we ever have access to something called an original. And once I realize my lived experience is being transformed, not falsified but transformed into art, the writer in me works to burnish and bloody it.

EH: There’s early on in Studio of the Voice the idea of the actually falsified thing (maybe just the artful thing or what was is being transformed as you write) set against the authentic, even static or Platonic “true” thing. Against something original or originating in sentences like “Tommy had been her true husband,” and “This, I felt, was my mother’s true family, to which I did not belong,” and “my birth was a mistake,” and “I didn’t feel like myself.” This language continues throughout, of course, in different forms, suggesting that there is something underneath that can’t be spoken, or even recognized, except through its unseating or shifting into art.

MA: I grew up in a family whose motto might have been DENY ALL. From my earliest memories I’ve been bent on penetrating the mysteries and subterfuges to get at what was really going on. Peeling back layers, getting at the truth—these never felt like decisions, more like strategies to survive. Writing has functioned as a corrective, a counterpressure.

EH: I wonder about this as a feature of this collection especially, but of your other work, too, that sets things up in categories—of course as all language does this—but then tries to efface those categories or those things. In one of these pieces, you say your father was erased in the family, but the piece (ostensibly about your mother) significantly materializes him. I wonder about the way these deflections and decategorizations work as insistences that reassure but that slide away—deny themselves—in the writing. There’s a quality of recursiveness around these slides, a revisiting or re-conception that seems like an attempt to stabilize the content or to make sure of the people you’re constructing.

MA: I wrote a scene in “The Mother Bed” that I’ve returned to several times. I’m digging around in the crawl space of the basement looking for a Halloween costume. I feel uncomfortable in this part of the house, as if it is off-limits. There I find a suitcase. Even though I know it is not mine to open, I open it. Inside the suitcase I find a cache of photographs documenting my mother’s first marriage and early life with my older half-sisters before her husband died.

I had spent so much of my early life wondering why my sisters had a different last name from me, why our mother didn’t seem happy to be my mother. There was such a difference between the mother I saw represented in those photographs and the mother I knew.

The scene was a wound I returned to over and over. The questions around this return inform much of my writing about my parents. Did I return to the scene in order to hurt myself and keep the wound open? To remind myself that there was something wrong with me? Or do I return to the scene because it refuses to be worked through once and for all?

It’s just the act of returning to my writing that revisits the pain, because I tend to just want to move on and protect myself from the experience of reading my work. Many times I wonder who wrote one of my essays. Where did it come from? It’s a mystery and a miracle.

EH: That scene is quite powerful—and your discovery later that the suitcase is missing, and eventually that its contents had been moved, presumedly by your mother, to a photo album that organizes and presents the photographs, normalizes them in that idiom of an arranged collection. It struck me strongly that Studio of the Voice as a (re)collection of past moments captured in images was itself an iteration of that scene or those scenes.

MA: I opened Pandora’s suitcase and couldn’t close it. I cast myself as a spy in the house of love. But it was more than a wound. I learned that I could trust my perceptions, my intuition, my emotional intelligence. I was right in thinking my mother had secrets and there was a troubling history in her mothering of me. I was inspired to hunt down what I’ll call the truth behind the endless deflections, denials, and secreting away of important stories. The truth is obviously a contested thing. My truth may be just that—my truth and no one else’s. Looking back, I think my opening of the suitcase was my first act as a writer.

Marcia Aldrich is the author of the free memoir Girl Rearing, published by W.W. Norton, and of Companion to an Untold Story, which won the AWP Award in Creative Nonfiction. She is the editor of Waveform: Twenty-First-Century Essays by Women, published by the University of Georgia Press. Her chapbook EDGE was published by New Michigan Press. Studio of the Voice from Wandering Aengus Press was released in 2024. Her website: marciaaldrich.com. Her essays have been included in The Best American Essays.

Emily Hipchen is a Fulbright scholar, the editor of Adoption & Culture, co-editor of the book series Formations: Adoption, Kinship, and Culture (OSUP), and an emeritus editor of a/b: Auto/Biography Studies. She is also the author of a memoir, Coming Apart Together: Fragments from an Adoption (2005). She’s an editor of Inhabiting La Patria: Identity, Agency, and Antojo in the Works of Julia Alvarez (SUNY 2013) and of The Routledge Auto|Biography Studies Reader (2015). She has edited The Routledge Critical Adoption Studies Reader (2023) as well as six journal special issues. Her essays, short stories, and poems have won multiple awards and have appeared in Fourth Genre, Northwest Review, Cincinnati Review, and elsewhere. She directs the Nonfiction Writing Program at Brown University, where she teaches nonfiction.