By Jael Montellano

Recently I spent time under my home country’s radiating sun. Lodged in the oven-warmth of car traffic, my aunt and I crawled past a rotisserie with the comida scent waking our unfed stomachs. Voices echoed from across the street in a mechanic’s shop where two young men called each other over the din. It was a familiar yet unrecognizable language.

“Escuchaste?” I said, children liberated from a school three blocks away filtering between cars.

My aunt replied, “Hablan Náhuatl.”

Náhuatl, the language of the Mexicas. Náhuatl, which was not taught in any school I attended, though English was. Náhuatl which these young men, my countrymen, had somehow preserved. And yet the traffic between us might well have been an ocean for our differences.

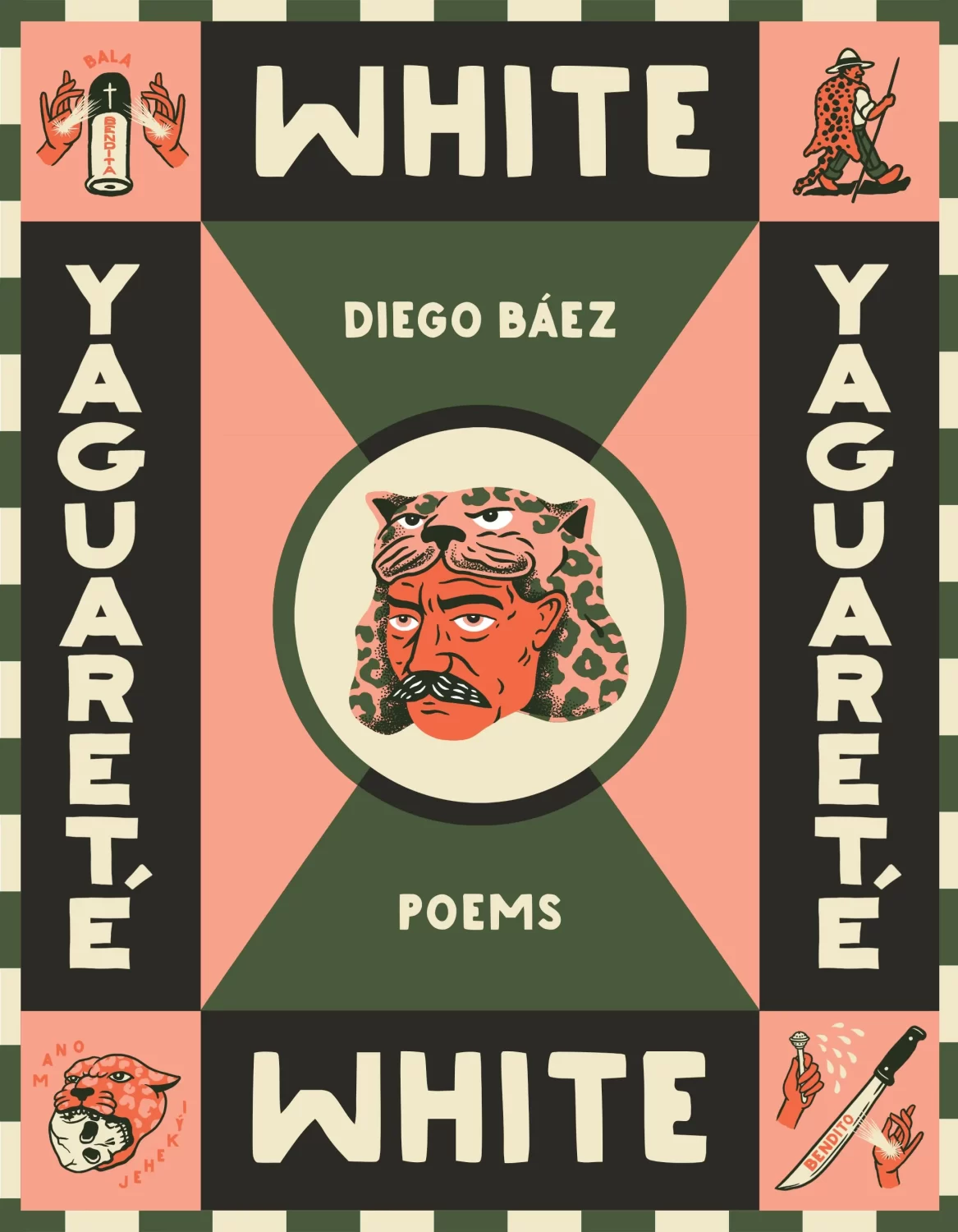

I bore this incident in mind as I read Diego Báez’s debut collection of poems Yaguareté White (University of Arizona Press). As a Paraguayan-American, Báez’s experiences overlapped some of my own Mexican-American ones, a reminder of the range and pervasive injury of colonization.

We corresponded to talk about his collection, about erasure, hyphenate identities, music and more.

Yaguareté is the word for jaguar in Guaraní, though you mention never having seen one in Paraguay. Yet it appears a personal symbol for you. Tell me about the jaguar mythology and its symbolism, what it means for you and for your collection.

There are definitely jaguars in Paraguay. I’ve never seen one because humans have driven them from much of their historical hunting range, which includes the regions I visit. Today, they prowl the alto chaco, lowland plains that span Argentina, northwestern Paraguay, and Bolivia. This region is also the ancestral homelands—and current home—to most of the country’s indigenous populations, who have likewise been decimated and displaced. Despite this, the jaguar, and their storytellers, live on.

One account I attempt to relate in the title poem of Yaguareté White goes like this: a Celestial Jaguar devours Arasy, goddess of the sky. The Celestial Jaguar goes on to raise Arasy’s children, Rupave and Sypave, until they learn the truth. The twins exact revenge by embarking on a slaughter, destroying every jaguar they can find. They kill all but one, a pregnant jaguar that represents a precarious potential, but also an attendant threat of impending annihilation. It’s a foundational myth of the Guaraní people, and so central to understanding their ordering of the world.

It’s important at this point to note that everything I know of Guaraní cosmology I’ve learned from the internet. Questionably reputable, often amateur sites that I almost always need Google to translate. More recently, I’ve sought out more meticulously composed—if not more reliable—sources of information. I stumbled across a PDF scan of “If God Were A Jaguar,” a chapter from Time and Memory in Indigenous Amazonia by Carlos Fausto, which describes the concept of the “acyguá,” a “jaguar-part of the person, representing the Other of the gods and the human desire for immortality.” Fausto introduces this idea as part of a conversation about “dejaguarization,” a process undertaken by native Guaraní at the behest of Jesuit colonizers to differentiate an immortal, divine “word-soul” from the base “word-soul,” a dichotomy which aligns nicely with themes of Yaguareté White.

What was the process of writing this collection? What have you learned about yourself as a Paraguayan-American through its journey?

In the many years it’s taken for this book to emerge, the most important thing I’ve learned about myself as a Paraguayan-American is that this hyphenate identity is indeed mine to claim.

Almost all of the Paraguayans I’ve met in the States are first-generation like my father. So I never thought to use this demographic label to name my own experiences. I’ve always called myself the son of a Paraguayan father and a Pennsylvanian mother (the etymological complement of Paraguay’s roots in “water” [y] and Pennsylvania’s in “wood” [sylva] resonates with me). Only as the final manuscript changed hands and entered the editorial process did I really begin to embrace this name for myself. This feels like a very positive development.

I will say also that what it means to be Paraguayan-American will mean many different things to many different people. I wonder how that will change in the future. I certainly hope more writers and artists emerge from our ranks. It would be wonderful to see folks follow in the footsteps of women like Claudia Casarino, Miriam Rudloph, and Faith Wilding, incredible Paraguayan-American (and -Canadian) visual artists. You should absolutely check out their work!

Some of the collection deals with the erasure of the Guaraní people. This erasure is also mirrored within your own personal loss of Spanish and Guaraní languages. Can you share some of the linguistic history you have learned for yourself about Guaraní and the effects of colonialism on the language?

Erasures of the Guaraní people have occurred in peristaltic waves. In the earliest days, many, many people perished. Many intermarried and interbred, not always in that order. Others fled. By one morbid measure, the Guaraní were lucky. Other peoples had existed who we only write about in the past perfect.

An optimistic glimmer: erasure implies memory. Otherwise, how do we know what was lost?

So we remember the 1530s, when the Spanish (and later Portuguese) crowns established outposts deep into the vast acreage that became Paraguay. Jesuits soon followed, founding and administering missions called, creepily, reducciones, or “reductions.” In a move cited by some scholars as an example of “benign colonialism” (I find “marginally less despicable” more apt phrasing), the Jesuits codified the language of the Guaraní into Latin. This act of linguistic petrification forever changed the future of the Guaraní, and Paraguay, and my ancestors, and my descendants.

In a wrinkle characteristic of Paraguay’s whiplash, pendular history, the early republic after independence sought to ban the language for a hundred years, until the 1960s skated around. In 1967, the dictatorial regime of Alfredo Stroessner declared Guaraní a national language of Paraguay (a “benign dictatorship”?). Of course, this came at the cost of another dozen or more indigenous languages still spoken in Paraguay today.

In 1992, after Stroessner’s fall, the country drafted documents to replace the 1967 constitution, and Guaraní was finally recorded as one of two official languages, together with Spanish. Meaning it is taught in schools and raised onto an international pedestal as an example of cultural conservation. I question whether the living Guaraní would call it that, those who have been relegated to intentionally impoverished communities at the outskirts of mainstream society. It’s a disturbing phenomenon, when a nation-state elevates one cultural element of a marginalized people at the expense of the actually living people. It feels like a kind of parallax, a sinister move to simultaneously preserve and downplay, that results in the diminishment of an aboriginal population. Call it the peristaltic parallax of genocide, a frightening reality in unfortunately many parts of the world.

Tell me about the musicality of Spanish and Guaraní and the role music plays within your collection. How do you revise a line for it when threading languages together that may sound incongruous?

I learned only recently about the binary and ternary rhythms of polka Paraguaya, music I grew up groaning over but now appreciate in all its quirky quickness. I’ve tried—Lord knows I’ve tried—to understand the difference, but I could not for the life of me tell you anything about binary or ternary rhythms, other than their definitions appear to include a number of fractions. But I’ve always enjoyed music with distinct basslines and complex cadences. Part of why I’m drawn to the music of Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and Phillip Glass, but also to Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson, and Ron Hardy is the way overlapping, competing rhythms interact in the ear. A few of the poems in Yaguareté White employ complicated syllabic schemes, which feels like an echo of this music. That propensity has got to come from somewhere.

As for lyrical incongruity, if a line produces meaningful dissonance as an aftereffect, I think that’s something to savor, especially since so much of the book concerns itself with mismatched knowledge, ontological uncertainty, epistemological inexplicability, linguistic contradiction, and questions of competing identities. I hope readers stumble on certain lines. I do.

I once asked a thriller writer how they wrote through grief. Stumped, they told me they hadn’t. I now know I should have asked a poet! And in particular, one that knows separation from their ancestral land. How did you write through grief in this collection? What tools and guidance did you seek to help you, particularly given that the landscape of Paraguayan-American writers is thin? And I mean any tools; books, movies, people, elements, food. (On some level, I realize the writing is the tool.)

I wouldn’t describe the foremost emotion I feel toward Paraguay as grief. (Maybe it is that, but I’m not ready to describe it as such.) It doesn’t yet feel so severe. Nostalgia is maybe more accurate, a pain that accompanies loss.

But I think you’re right: the writing is the tool, for me anyway. I don’t think about this often, but I’ve been absent from so much of the familial loss that has occurred in the time it has taken for my book to come together. Due to logistics (distance), circumstances (COVID), and personal choice (cowardice). Because I have not sat with grief, it feels like an appropriate time to confront it by naming those who have passed:

Mis abuelos: Nicasio and Hilda. Tío Arnulio before them. Tía Luci most recently.

But also my dad’s host mom, Nola Gramm, and dad, Robert. A host brother, Brad.

My uncle John.

Many of the above I name in the book, which felt important. If I can’t confront this loss in life, at least they can live on in my small contribution to American literature.

Your collection addresses a disconnectedness felt from being raised in places like Central Illinois, away from Latinx populations and with limited access to your ancestral language and land. As you launch this collection, do you think about audience, about who will come to the work and what they will or won’t understand? What kind of reader do you hope for your collection?

In a way, my ideal readers are my brothers, Armando and Miguel. They’re the only people on the planet who share experiences with the primary speakers of the poems in Yaguareté White. Back in August, we went camping overnight at Comlara Park in Central Illinois. I read from the ARC of the book to them. My first public performance of the work. It felt incredibly special to share it with them.

That said, my family has already begun to point out moments of memory consolidation, or exaggeration, or falsification. As a poet, I see truth in those maneuvers. As in, I see it as my responsibility to assemble enough moments of authenticity that it conjures or recreates a sensation for any reader, regardless of actuality or ideal. I find this to be true regardless of whether it’s factual.

You ask about audience, about what readers will or won’t understand from the poems. I think about my tía Amada, my father’s oldest sister. She likes every single one of my Facebook posts and adds animated gifs and emojis in the comments. I’ll get her a copy of the book, and she’ll be so proud. But what of it will she understand? She won’t be able to read most of it, but I’m positive she’ll wield it like a badge of pride. That’s enough for me.

Which Paraguayan and Latinx writers and poets do you believe should be more known, read and translated beyond their borders?

Recently, I read Argentinian maestra Hebe Uhart’s posthumous collection of crónicas, A Question of Belonging, in which she names Elvio Romero and Rafael Barrett (a Spaniard by birth, Barrett referred to Paraguay as, “mine only land, which I love deeply,” and it was the site of his literary production and primary impact, both as a writer and anarchist organizer). I hadn’t heard of either writer, so I’m grateful for these breadcrumbs that have led me to discover these writers the way colonizers “discovered” the Americas: they were always there, but now that I can name them, perhaps others will learn about them, as well.

Certainly C. E. Wallace, a Paraguayan-born poet who published a collection of Spanish-language poems, Juego de Palabras (Valparaíso Ediciones, 2023), whose work is rich with wordplay and spatial exploration across the page. It’s been super cool to connect with Wallace and I’m optimistic about the future of Paraguayan-American poetry!

I’ve loved Elisa Taber’s translations of Miguelangel Meza’s poems and selections from Damián Cabrera’s lyric novel Xirú, which takes its title from a “Portuguese word of Guaraní origin used by Brazilians to refer to Paraguayans at the border, which shifts from meaning “friend” to “invader” or “fool,”” according to the translator’s note that accompanies the text at Words Without Borders. WWB has put up an impressive array of South Am lit in translation, and I highly recommend supporting their projects.

Diego Báez is a writer and educator. He is the author of Yaguareté White (University of Arizona Press; February 20, 2024), a finalist for the Georgia Poetry Prize and a semifinalist for the Berkshire Prize for Poetry. A fellow at CantoMundo, the Surge Institute, and the Poetry Foundation’s Incubator for Community-Engaged Poets, Báez has served on the boards of the National Book Critics Circle, the International David Foster Wallace Society, and Families Together Co-operative Nursery School. His poems, book reviews, and essays have appeared online and in print. He lives in Chicago and teaches at the City Colleges. Connect with Diego at diegobaez.com.

Yaguareté White (University of Arizona Press; February 20, 2024)

In this debut collection, English, Spanish, and Guaraní encounter each other through the elusive yet potent figure of the jaguar.

The son of a Paraguayan father and a mother from Pennsylvania, Báez grew up in central Illinois as one of the only brown kids on the block—but that didn’t keep him from feeling like a gringo on family visits to Paraguay. Exploring this contradiction as it weaves through experiences of language, self, and place, Báez revels in showing up the absurdities of empire and chafes at the limits of patrimony, but he always reserves his most trenchant irony for the gaze he turns on himself.

Notably, this raucous collection also wrestles with Guaraní, a state-recognized Indigenous language widely spoken in Paraguay. Guaraní both structures and punctures the book, surfacing in a sequence of jokes that double as poems, and introducing but leaving unresolved ambient questions about local histories of militarism, masculine bravado, and the outlook of the campos. Cutting across borders of every kind, Báez’s poems attempt to reconcile the incomplete, contradictory, and inconsistent experiences of a speaking self that resides between languages, nations, and generations.

Yaguareté White is a lyrical exploration of Paraguayan American identity and what it means to see through a colored whiteness in all of its tangled contradictions.

Jael Montellano (she/they) is a Mexican-born writer, poet, and editor. Her work exploring otherness features in ANMLY Lit, Tint Journal, Beyond Queer Words, Fauxmoir, The Selkie, the Columbia Journal, and more. She practices a variety of visual arts and is currently learning Mandarin.