Shards of morning clamor echoed off the city. They reflected into George’s apartment like light or some other almost visible thing. She wished it had been light, a warm insertion as gradual as poured honey, rather than those blarings blanketed in immediacy. The howling brakes or crackle of the 161 bus door openings, all riptides of aliveness she didn’t want or need. George covered her ears and winced as the world behind the window closed in. She never imagined herself longing to be awakened by the light.

George switched her end-table lamp on, 5:17 a.m., and stared out onto the brick wall her building faced just above the dumpster hidden in the alley. She reached for her father’s old copy of Morrison’s Song of Solomon. George couldn’t shake her inability to call the book anything but his, even after her father started calling it hers long before his passing a little over a year ago. There was something about the dead still being in possession of a thing that she needed to hold onto until she couldn’t. She smelt the book’s age and savored the tiny weight of its bigness before opening it to one of the dog-eared pages she didn’t choose.

“Wanna fly, you got to give up the shit that weighs you down.”

It was the only book she’d seen her father read all the way through. As in life, he’d dabble until his attention waned, but he always came back to Song of Solomon. George didn’t know if it was the pulse or sharp resonance of the people among the pages, but the book spoke to him the way the world should have. She found herself falling into his annotations more frequently, mouthing the words he circled and dragging the long i and o sounds the way he used to. She would curl up and study his smudged notes, deep underlines, and double circles, hoping that a memory could always feel that present.

Her father presented the book to her like he was passing down a family heirloom; it was a first edition, so might have been the closest thing they had to one. George watched him cradle the edges like he cradled her when she didn’t know what cradling was, and when she took it, she held it the way she imagined she’d hold his heart.

“It’s the only thing I have to give, George,” her father explained. “The only thing that means something.”

George hugged the book, “Why do you say that like it isn’t enough?”

She watched him smile and felt the room tighten around them, every hidden piece of her father grew with the slow off-white reveal of his front teeth. It took so little to make sure someone didn’t feel small, George never understood why that reality mattered to so few people.

George peeled away from the book long enough to get dressed earlier than she normally did. She would find out if a particular grant proposal went through at work that afternoon, one of which the anticipation had been building for weeks. To call her proposal caseload inevitable was an inevitability, but George didn’t mind. She’d been grant writing for nearly a decade, and in that time she was one of the six people of color hired through what was a mid-sized revolving door NGO. She was also the only one that stayed. George was not so subtly assigned any proposals pertaining to “urban, diversity, or grassroots” initiatives seeking funding, as that language had a tendency to trigger a large majority of her co-workers. The work was rewarding though, and no matter which way the workplace minutiae tilted, George was proud of what she did. This particular proposal was for a literacy initiative centered around marginalized and low- income communities. She didn’t mind relishing in the team approval of sports or activity-based successes, but getting a win for something other than those excited her. Especially a cause for books, especially a cause for books, for Black people.

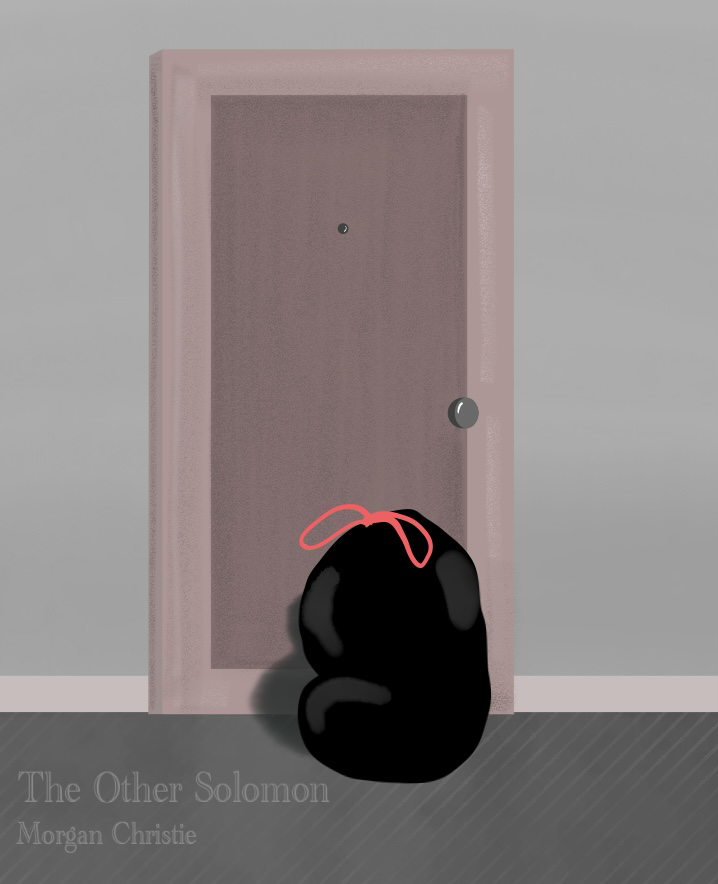

George headed out and was hit by the same rancid odor she’d been plagued with for the past three days. She covered her nose after glancing at the still full garbage bin outside her door. The trash removal service technician had apparently missed her apartment that week, and her emails to the apartment manager continued to go unanswered. George thought about drafting another email right then and there, but if she did she’d chance running into Mr. Seltzer. Mr. Seltzer had lived across the hall for the past twenty years. When she moved in almost a year prior, he was the only person to welcome her to the floor. Maybe once every couple of weeks, he’d stop by with lox or latkes and George would accept even though she was not overly fond of fish. They’d chat at the door for hours, if he had his way. He’d mostly talk about Mrs. Seltzer, about their life and about her death. He was lonely, as lonely as George felt after her father died. “When you love someone that dies,” Mr. Seltzer said to her once. “I don’t think you can ever be as happy as you were when they were alive. Happy, yes. As happy, I don’t think so.”

He was right, George thought, she hadn’t heard something so right in a long time. She wondered why she never told him that. George rushed down the hall and continued in her avoidance of Mr. Seltzer, the non-malicious neighborly kind she picked up a few months after moving in. She rushed to work even though she didn’t have to, quickly blending into the decipherable noises she loathed before the world was bright.

George would get the call about whether the literacy proposal was accepted around three or four that afternoon. It was all she could do to focus on anything that morning. She wasn’t an anxious person, but the anxiety she’d feel on proposal notification days could have fooled her into believing she was. The balance between pressure to perform for the cause and for oneself tugged on George’s conscience; would she be harder on herself for being the plug that didn’t get kids a lot like her the resources she rarely had, or for being the sole minority left in the office that failed her community. The expectation always went unspoken, but was as permanent as those inevitabilities. If someone else in the office didn’t get that grant, it would just be hard luck or stiff competition, but if George didn’t get it, she must have done something incredibly wrong.

When lunch rolled around George decided to visit a nearby variety store. She pulled the shop door open and exhaled as the double-toned sound effect chimed and reminded her she’d never lived in a home that had a doorbell. She meandered the aisle, snapshots of her childhood shelved like overstocked excess the shop owner needed to be rid of. Sour key candies and single-pack noodles lining the walkway she could barely squeeze through. George turned the last corner of the shop and stopped where the edges collided, she saw it sitting there in a place it clearly wasn’t meant to be: a jar of Solomon Gundy.

The fish paste was a favorite of her father’s and George remembered sharing bites with him on crackers or cucumbers. He’d scoop out the spread in distinctly uneven clusters, the scent of vinegar all around them. Her father would press the fish against its base and give George the bigger helping even though she was so much smaller. They’d bite down together, her father slowly savoring every chew like there wasn’t a nearly full jar next to him, and George would pretend to love it because he did. Only pretend, because she wasn’t overly fond of fish. She grabbed the jar she was sure someone purposely stored at the back of the shop and checked out before making her way back to the office. George rolled it around in her rounded palm and already knew the spot in her cabinet she’d put it in. She knew she wouldn’t eat it, but she thought it might be nice to know it was there.

Back at the office the afternoon went by much like the morning, and when three o’clock hit, the phone rang like clockwork.

“Hello,” George answered before the second ring.

“Hi,” an unfamiliar voice replied. “Can I speak with George Campbell, please?” “This is she.”

The voice hesitated, “This is George?” “Yes, it is,” George said.

“Oh, okay,” the voice still hesitated. “Is it short for Georgina?”

Awkward laughter followed the question and George maintained that she was not going to join in. Maybe earlier in her career or even on another day with another person, but not that day. She could have told them that it was her father’s name and he gave it to her like he gave her his book; that she was bullied for having a boy’s name even though her father told her there was no such thing, names were just names; that when her mother left to marry her stepfather she told George that she’d be better off with her father, that every piece of her was built from him, that that was why she let him name her George, because as soon as she saw her daughter she knew that she would always be more his than hers. On that day, George just sat silently on the line and refused for it to be her responsibility to ease someone else’s discomfort in their perception of what she should be.

“Well,” the voice finally stopped laughing. “I’m calling to inform you that your recent grant proposal has been accepted . . .”

The voice faded into memory as soon as George heard those words. Her reaction wasn’t that of elation, but relief. She knew that wasn’t good but it existed just the same, and she took that relief to her co-workers, and then to her apartment, and then to the cupboard where she displayed her little jar of Solomon Gundy. Then she took it to her father’s book where she chose another dog-eared page and fell back onto her bed.

“If you surrendered to the air, you could ride it.”

George hadn’t realized she’d fallen asleep until she was awoken by continuous knocking at her door. She jumped up and stumbled to the door, her legs taking longer to wake than the rest of her. George glanced through the keyhole and recognized the apartment manager immediately. The woman wore the same bright cherry lipstick she always did, but George could never remember her name.

George opened the door, “Hey, how’s it going?”

The manager smiled, “Good thanks. Sorry I didn’t respond to your emails, I wanted to check on your inquiries first.”

She went on about managing multiple properties and sometimes getting confused about which service belonged where and with whom.

“But there’s no valet waste service in this building,” she said.

George was taken back, “What do you mean? I’ve left my garbage out in the hall since I moved in here. It gets picked up on Tuesdays.”

The apartment manager squinted a bit, “Well, garbage does get picked up on Tuesdays, but from the dumpster. You’re probably at work when it does?”

George agreed, “I’m sure I am, but that doesn’t explain ho—” “Oh,” the manager interrupted. “Solomon takes yours out!” George was even more taken back, “Who?”

“Solomon,” the manager pointed to Mr. Seltzer’s door. “I’ve seen him grab yours when he takes his down.”

George wasn’t sure if she was more surprised by the garbage reveal, or that she’d known Mr. Seltzer for a year and didn’t know that his first name was Solomon.

“But,” George said. “This has been happening since I moved in.”

The manager nodded, “He was a nice guy.” George replied, “Yeah, I’ll have to thank him.”

Then the manager’s face went cold and she just stood there for a second before biting her bottom lip. George watched the cherry red stain the bottom of her front teeth.

“I’m sorry, but I thought you knew,” she whispered. “Solomon passed away. His son had been trying to reach him and couldn’t get through. He was found in bed a few weeks ago. Stroke, I believe.”

George looked for something to say. She glanced at Mr. Seltzer’s door and back at the stain on the manager’s teeth.

“You’ve got a little something here,” George motioned to her own front tooth. The woman covered her mouth, “Thanks.”

“No,” George said. “Thank you for letting me know.”

The manager left and George closed the door. She stood there for a moment, standing in front of the closed door the way she would to listen for footsteps. She made her way into the kitchen and opened the cupboard where the Solomon Gundy was. She didn’t have crackers or cucumbers, but she did have a spoon. George twisted the lid and heard it pop in relief before the smell jumped around the room. She scooped a smidgen from the edge of the jar and held it to her lips as she read the name on the bottle like she’d never seen it before. The thought crossed her mind, but George put the spoon down instead.

She put on her slippers and walked into the hallway without having to check to see if Mr. Seltzer was there. She grabbed hold of her garbage and walked down to the alley she’d only seen from her window. George heaved the bag higher than she needed to and hoped it would hit the bottom of the dumpster in a double- toned thud, but it only hit more bags, and sounded like it hadn’t fallen at all.

George found her way back upstairs and in her bed with little recollection of how she got there. It was dark enough for her to need to turn her lamp on, so she reached out into the darkness and flipped the switch. She grabbed Song of Solomon but didn’t turn to a random page this time. George opened the book to a page near the end and followed the trace of her father’s circles round and round as they danced through the corners of the line. Her eyes traced the one time he made three circles until she saw nothing but lead etchings hug every letter of the line he saw more clearly than anything else. George stared at the words and wondered if what lay inside the three instead of two circles would have meant something to the other Solomon, as much as they meant to the Georges.

“I wish I’d a knowed more people. I would of loved ’em all. If I’d a knowned more, I would a loved more.”

She wondered as she faded into another sleep she didn’t know she was falling into, only realizing in small bursts throughout the night as she continued to be awakened on and off, by the light.

Morgan Christie’s work has appeared in Callaloo, Room, Hawai’i Review, and elsewhere. She is the author of four poetry chapbooks and her full-length short story manuscript “These Bodies” (Tolsun Books, 2020) and was nominated for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award in fiction. She is the 2022 Arc Poetry Poem of the Year Winner and her collection People Without Wings is the winner of the 2022 Digging Chapbook Series Prize (Digging Press, 2023). Her first essay collection, “Boolean Logic” is the winner of the Howling Bird Book Prize (2023) and her novella Liddle Deaths (Stillhouse Press) is due out in 2024.