Prior to Dwarf: A Memoir, the only book I ever bothered to read (and finish) about “little people” was The Hobbit. Unlike The Hobbit, Dwarf is not epic medieval fantasy, nor is it about hobbits or “actual” dwarves, neither of which exist I think. For the sake of political correctness, it’s rather a biography of a “little person”: one in whom we observe the sort of dwarfism—more or less obvious signs of slowed, stunted, or otherwise abnormal growth—that can result from any one of 200 to 300 or more distinct medical conditions.

Prior to Dwarf: A Memoir, the only book I ever bothered to read (and finish) about “little people” was The Hobbit. Unlike The Hobbit, Dwarf is not epic medieval fantasy, nor is it about hobbits or “actual” dwarves, neither of which exist I think. For the sake of political correctness, it’s rather a biography of a “little person”: one in whom we observe the sort of dwarfism—more or less obvious signs of slowed, stunted, or otherwise abnormal growth—that can result from any one of 200 to 300 or more distinct medical conditions.

To put politically incorrectly, I’ve read a book about a “midget.”

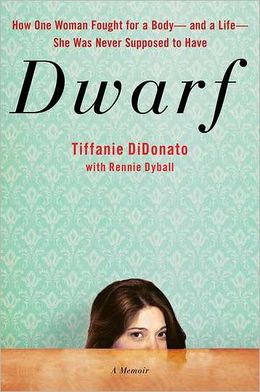

Co-written by People.com editor and author Rennie Dyball, Dwarf is the autobiography of Tiffanie DiDonato, who at birth was diagnosed with diastrophic dysplasia. For readers unsure of what that is exactly, DiDonato goes through the trouble to “save you the trip to Wikipedia”, explaining it as “a very rare type of dwarfism that results in short stature, joint deformities, and very short arms and legs.”

“From birth to the age of twelve,” she writes, “my arms were so short that I couldn’t reach my own ears, or other parts of my body for that matter.”

Starting at the age of 12, Tiffanie underwent a series of then-controversial bone-lengthening procedures, which essentially involved breaking/sawing the bones in her arms and legs into segments, using external metal pins and braces to align them, and regularly separating the bones a millimeter at a time (by turning a screw)so that the bones regenerate in the negative space between them and fill in the gaps—effectively lengthening the limbs.

According to Little People of America (which apparently frowns upon the aforementioned procedure), one is considered a “little person” if he or she is four feet, ten inches tall or shorter. Today, DiDonato is 4’10”; in childhood, however, prior to her life-changing surgeries (not to mention her decision to go well beyond the typical two to three inches people typically expected to gain from them), she stood at only 3’8”—and apparently “wasn’t expected to grow any more” at that point.

In other words, she wasn’t expected to live beyond a state of perpetual dependence. “Undergoing bone-lengthening surgery,” DiDonato insists, “was about becoming independent and being able to get from point A to point B in a timely manner, perhaps while carrying some belongings with me at the same time.”

“The body I was born with wouldn’t allow me that simple exercise in freedom.”

Had she not undergone the radical Ilizarov apparatus, suffered all the excruciating complications and pains of every variety (muscle, bone, nerve, and vascular) that came with it, and endured her brutal post-operation therapies (over several years), she wouldn’t be enjoying the freedom she has now. Were it not for abundant reservoirs of fortitude and tenacity (which she inherits from her strong, supportive, and above all loving military mother), she wouldn’t be much better than a poor victim of a rare, misfortunate handicap.

Instead, she’s more than that. She’s Tiffanie DiDonato, a beautiful woman, a mother, a wife to a very handsome Marine, and all-in-all an awesome human being.

♦ ♦ ♦

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

—Emerson

Tiffanie DiDonato is not a “remarkable” person—and I mean that as a compliment.

All too often it’s the case that we consider something or someone “remarkable” because he, she, or it was once perceived to be somehow “unremarkable”, or incapable of going beyond its unremarkable state—or both. In America, we like to lower our expectations of others; reader, more often than not, you’re someone who charges another insignificant until proven noteworthy—and you do it for the same reason you’d charge someone guilty until proven innocent (if you’re somewhat fair-minded), guilty until distracted by new news (if you’re of the sort that value trends), or guilty until…well…until you die, really (if you’re the begrudging, irrational type—like many if not most people I fear).

It seems that there will always be people who hate LeBron strictly because they’re Kobe fans; and there will always be people who hate Kobe simply because they’ve made up their minds that he’s a rapist (in the same way five-year-olds insist on believing in Santa Claus). It’s no different when it comes to the rubric of remarkability: one’s perceived social value is often a consequence of a sticky sort of ignorance.

It would seem that it’s impossible for one to stubbornly adhere to ideals that make sense to him without being stubbornly dismissive of ideals that don’t make sense to him. Truths can’t exist without their corresponding lies for the same reason you can’t believe in the Judeo-Christian devil without believing in the almighty Judeo-Christian nincompoop responsible for his existence. If you have a perspective on what ought to be or what is, you likely have a corresponding perspective on what ought not to be or what is not as well.

And since we’re (for the most part) all entitled to our beliefs and (again, for the most part) encouraged to hold onto them dearly, it’s fair to say that everyone is a stubborn and dismissive disbeliever of something at some point. It’s as if we’re hardwired to be judgers; worse yet, we overestimate ourselves in our simultaneous underestimation of others—and history doesn’t lie.

My first reaction to the story of DiDonato was that she’s a “remarkable” person…only because she’d been born with “third-degree dwarfism” (I’m quoting her doctor—apparently there’s no such condition). Would she still be “remarkable” if she weren’t born like that? Honestly, before even reading the book, I pitied her because I knew she was “disabled”—and aren’t we all taught by our parents (who mean well) to “feel bad” for “disabled” people? Aren’t we all taught to see “little people” as victims? True, there are parents who refuse to instruct us in that way at all; instead, they coat their prejudices with a thicker veil, encouraging their children to treat “them” with respect, or as they themselves would prefer to be treated—to “do unto others as you would have others do unto you” (a truly meaningless maxim which has proven to be about as useful in adulthood as training wheels and nursery rhymes).

Even in that respect, the prejudice still persists, for what else rouses within those parents the need to instruct their children as such in the first place? Assuming an eight-year-old doesn’t know what the word “midget” is yet, much less understands the negative connotations attached to it, when he or she happens to spot a little person approaching, pushing his shopping cart down the frozen food section towards you and your watchful kid, what it is it that motivates you to drop the last box of hot pockets, shut the freezer door, and desperately rush to whisper into this child’s ear to do this or don’t think that at all? Why do we even bother? (We might as well just tell the kid, “Stop staring, leave him alone, he’s sub-par, he’s a midget, now look here and tell me which one you want: ham & cheese or beef taco.”)

The answer is pity.

We reduce people to the sum of their purported “disadvantages”—and I daresay we do it because it allows us feel better about ourselves. After all, no “midget” could ever be expected to pummel through the lane like a freight train and finish a fiery fast break with a thunderous foul-line dunk in the NBA. No “midget” could model for American Apparel, or become a Victoria Secret Angel for that matter. No “midget” could ever star as one of the leads of an acclaimed television series, become everyone’s favorite character in it, win an Emmy and a Golden Globe for his performance, and marry a hot, full-sized, liberal theatre chick (you know, the dark and freaky kind)…right?

If you clicked on that link, or if you already knew who Peter Dinklage was, you might realize that you’d be wrong in some cases. Will a little person ever hit a game 7-winning walk-off homerun? Probably not—but I sure as hell won’t either, even if I have the so-called “advantage” of being a normal, full-sized adult.

If there’s anything remarkable about DiDonato, she gives you the distinct impression that she’d rather you not feel sorry for her. Much of the accounts she shares in Dwarf encompass parts of her life that are as commonplace as any in any normal American girl’s life (e.g., crushes; making friends with new classmates after moving to San Antonio; seeing her old friends move on upon returning to Massachusetts; mediating her girlfriends’ love triangles; talking to her best friend, Mike, on the phone for hours, etc.). Her tone and indeed much of how she presents herself don’t strike me as belonging to a girl who hated her life, or nowadays a woman who seeks sympathy. The little woman in that Nightline interview certainly doesn’t strike me as bitter.

When she relates an important conversation with her father over ice cream in which she asked about boys, wondering what they found “beautiful” (to which he sweetly responded by making an hourglass shape with his hands and reassuring her that she had that), I see a warm father and a typical tweenaged girl—not a dwarf (or a man who had at one point actually considered giving her up for adoption). When she swoons in the book over her husband Eric, her real-life knight in shining armor, I can’t help but visualize a woman in love—no more, no less. When she says things like “let’s be perfectly clear: I am not a midget, I am not a dwarf—please, just call me Tiffanie,” I’m mostly left quite satisfied with doing just that, and seeing her not as a “little person”, but rather as “a woman with ideas, talent, and a sharp tongue” (emphasis mine).

There is nothing “special” about her. To say that there is seems inherently pejorative.

♦ ♦ ♦

“Players playing that well don’t usually come out of nowhere. It seems like they come out of nowhere, but if you can go back and take a look, his skill level was probably there from the beginning. It probably just went unnoticed.”

—Kobe Bryant on Jeremy Lin

I guess if one insisted on considering people like DiDonato or Dinklage “special”, then he or she is more than welcome to, especially if it’s on the basis that they’ve fought for and earned their happiness and peace of mind; many these days, disabled or otherwise, fight very little for anything and earn very little in return. But there is something shady about appreciating a little person’s achievement as such that it comes as a shock—that he or she is “remarkable” insofar as he or she was never supposed to surpass “unremarkable”.

Read the excerpt below. Read what DiDonato said to her orthopedic surgeon in order to strip him of his reluctance to push the conventional boundaries of the procedure, to convince him she was ready to take on the pain of conquering her life-limiting debilitations—

—because she was barely a teenager when she said all that.

You know the second you read about the early, elementary pride she once felt as child when she’d use salad spoons to turn on light switches without the help of her parents that she always had it in her to be more than just a hopeless casualty of diastrophic dysplasia. When you see the kind of mother she has, one who time and again rebuffed the idea that someone would “follow [Tiffanie] around until she’s an old lady,” or that she’d have to “suck up to a caregiver all her life because she can’t do something herself,” you know the girl was never meant for a life of unchallenged weakness or subservience.

DiDonato was never “unremarkable” to begin with. Her successes were never surprises (at least to the people who mattered to her most).

That said, I’m not saying you’re wrong to have doubts, or that you should shed yourself entirely of your reservations. Just as you’d have good cause for believing that there won’t be a black Julia Roberts or a black Meryl Streep any time soon, or that someone who doesn’t speak English could ever be elected to congress, you’d have equally good cause for expecting little people not to grow larger than life. Many would rather settle with being bitter and pitied and given handouts anyway (and they’d deserve it because they don’t know any better—and it’s never entirely one’s fault for not knowing any better).

But thanks to books like Dwarf,we’re routinely—and healthily—reminded that we should also expect the unexpected. You just really never know—especially with those who believe in themselves.

Allow me to close on this:

Around this time a year ago, some bitter Knick fan in Jersey was considering dumping his allegiance to the boys in blue and orange and becoming just another Laker fan living in New York, for he’d grown weary after a long decade of basketball mediocrity. He didn’t know what 2012 would bring him and his entire city, that in less than a month’s time, some no-name, Harvard-educated Asian dude from the D-League sitting at the end of the bench would mean all the difference between another losing season and the revitalization of a once storied franchise—that he’d singlehandedly put his team back on the map in one of the greatest, most uplifting sports stories ever.

Ask Derek Fisher. Really, you just never know what’ll hit you.

♦ ♦ ♦

EXCERPT from Dwarf:

‘Do you know what four inches feels like?’ I asked. I wanted him to know I was a veteran and not going into all of this blindly.

He shook his head no.

‘Four inches was more pain than I ever thought possible the first time I had surgery. Every night, I felt the muscles in my legs twitch and jolt and bang against me from the inside out. It was horrible, and while I was doing it, I swore I never wanted to feel that much pain again. But now I know that I need to do this again. I also need it to be worth all that pain.’

A version of this was published on PolicyMic (01/03/13) and on The Salem Thinker Post (01/19/13).

Emen William Garcia graduated from NYU in 2010. Afterwards, he found his calling during an editorial internship at The Overlook Press, where he realized how much he loves books. He hasn’t looked back ever since. He’s a proud, American, hybrid-hipster journalist from New York who fancies himself a “future important person”. He prefers MSNBC, watches Real Time with Bill Maher, reads Christopher Hitchens, reads a lot, dreams a lot, eats a lot, and hates libertarianism (a lot). Pray that his life goes somewhere good.