One afternoon in Chicago during the summer of 2017, I saw a bumper sticker in the shape of a paw print and the words “rescue mom,” which I read not as a descriptor, the emphasis on rescue, like—rescue mom, but as an imperative, the emphasis on mom, like—rescue mom.

Mom had been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in June of that year, and I kept seeing signs pointing to it—specifically pointing to the fact that I couldn’t rescue her, that I’d never been able to before, and I certainly couldn’t do it now. I hadn’t seen her in a couple years—three to be exact. We have a complicated relationship; her lifelong struggle with depression and alcohol rendered her absent for much of my life.

The month after mom’s diagnosis I flew to Boston from my home in Chicago to see her. My sister, who lives in Boston, led the way to mom’s room in the nursing facility she’d been transferred to. I walked past the residents sitting in a row of chairs near the front desk. We found mom’s room, but she wasn’t there. We went back out into the hall and I watched as nurses wheeled residents from their rooms to appointments and back again. Some of the residents looked like they were doing okay—they moved under their own power, and had conversations with their caretakers. Others weren’t doing so well; one man was parked in front of a TV, his still silence punctuated by regular screams. At the far end of the hall, a nurse pushed a woman in a wheelchair; she was dressed in a hospital robe, and listing to one side. She was skinny, and as her wheelchair approached, I noticed that she was virtually bald—a faint spider web of white fuzz on her crown, and what looked like a single dreadlock on one side of her head. “Jessica,” the woman in the wheelchair said, and I was shocked into recognition. It was like seeing one of those digitized missing person images on the news where a photo of the person as they last appeared is used as a baseline, and the image morphs to what they might look like now. Only there were no calculations involved, no guesswork, just my mother in a hospital gown and a wheelchair. As the nurse wheeled Mom into her room, I saw another dreadlock, the size of a lab mouse, on the back of her head.

When I first stepped into Mom’s hospital room I couldn’t speak. My brain was stuck in the space that existed between remembering Mom the last time I’d seen her and what she looked like now. This conflicting visual information shut down my speech mechanism, and I couldn’t get it to start working again, so I sat in a chair across from her bed and tried not to stare.

“Jessica,” she said, her voice penetrating my frozen state, “what would you rather be doing right now, sitting here or watching paint dry?” She was trying to be funny, but my ability to pick up on humor lagged somewhere behind my ability to speak. I moved my jaw, tried to think of words, tried to perform the task of transmitting them from my brain into my mouth and using the power of my breath and my voice to project them out of my face and into the room. “What do you mean, watch paint dry?” I asked. “It’s an old joke,” she said. We didn’t hug, that’s never been our style. We didn’t say “I love you”—that phrase sounds like plagiarism when we exchange it—we just talked about nothing, and when it was time for me to leave, we didn’t even say goodbye in our primary language. She said “à bientôt,” which means see you soon, and I said “à la prochaine,” which means see you next time. Then I got in a cab headed to Logan Airport.

The next time I saw her she’d been transferred to home hospice in her condo and weighed in at 117 pounds. The dreadlocks were gone, having fallen out while she was being bathed; she was completely bald, save for a few tenacious strands of white hair. I’d just been to the doctor for my annual physical, where I weighed in at more than I’ve ever weighed in my life. It was as if there was a cumulative weight that Mom and I needed to maintain, and if weight came off one of us, it moved to the other to maintain equilibrium. Other things had been happening to my body too—I’d been fitted for bifocals, and my left heel hurt, so I’d been wearing orthotics. Mom was dying and I was aging, like I was being groomed to take over for her once she was gone, like there was a quota of old ladies in our family that had to be met.

She wanted to hug me; it was awkward. I leaned over from my seat and put one arm around her, the other went slack because I couldn’t fit both arms around her chair. Being this close to Mom was terrifying because I’ve always looked so much like her, and watching her deteriorate was like watching myself deteriorate. We have the same cheekbones, the same hooded eyes, and the same smile. We’re almost the same height, and have the same body type: sturdy, large breasted, big hipped—what some might call zaftig. I once showed Mom’s high school portrait to a friend who said: “You look angry in that picture.” People who know us mutually and haven’t seen me in a while sometimes call me by her name. Sometimes they look at me like they’ve seen a ghost—because they have, they’ve seen what Mom used to look like before she started destroying her body with alcohol, before she stopped taking care of herself.

When I got back home to Chicago, I called her; she sounded horribly depressed. “I love you,” she said. It was approximately the fifth time in my life that she’d said this, and it made me uncomfortable. “Aw, Mom, I love you too,” I said, partly because come on—she was dying, and partly because I thought I might mean it. Afterwards I stood in my kitchen, staring at the tiles above the stove as if they might tell me what to do next.

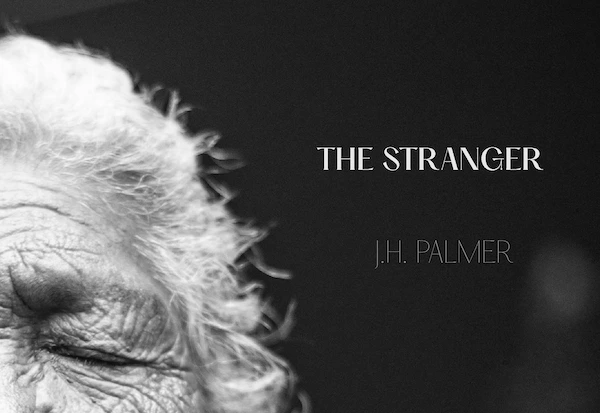

On one of my visits to Boston that fall, I found a 1957 copy of Albert Camus’ L’etranger in Mom’s condo from her freshman year in college. The text opens with: “Aujourd’hui, Maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas.” Which means: “Today, Maman died. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” The opening sentences in Mom’s copy were underlined. Above the text, in pencil, she had written: “not normal—should know when,” meaning that Meursault should have known definitively when his mother died. Above that, on the blank space before the chapter heading, she’d written “Stranger to world, to what should usually be accustomed to, would happen,” which I interpreted as her analysis of the book’s title. The word Etranger can be translated to mean “outsider,” or “foreigner,” and in British English the novel is known as The Outsider, which feels more accurate to me than The Stranger. Meursault’s disposition is outside of what is expected, which is, I believe, what Camus intended with the title. He said as much years after the book was published: “In our society any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.”

I was at home in Chicago when my sister called from Boston to say that Mom’s death was imminent. She’d been unresponsive for a number of days when Mary, Mom’s live-in hospice nurse, called my sister to say that Mom’s breathing had changed, and to come right away because the time was near. There wasn’t enough time for me to fly to Boston before she died, and I wanted to keep busy rather than sitting at home awaiting the news, so I went to work.

I made my commute to the Art Institute of Chicago as usual. It was a Friday in December, and work was wrapping up early for the staff holiday party. I didn’t tell anyone at work that Mom was dying; I’d gotten the news that Mom had terminal cancer my first week on the job in June, and the only person who knew why I was flying to Boston so much was my supervisor, because she had to approve all my requests for time off. She was amazing, my supervisor. She told me to take whatever time I needed, and she kept it confidential, per my wishes. I couldn’t stand what I anticipated the reaction would be if my new coworkers had known: the pitying glances, the refrain of “How are you doing?” The whispers of “Her mom has cancer,” and, eventually, “Her mom died of cancer” when all I wanted was one space where I could be unremarkable—not someone with a dying family member, but just another employee clocking in, completing tasks, attending meetings, chatting with coworkers, and clocking out.

When people asked me about Mom while she was sick, I had to consider my response. If I told the whole truth, they’d know that prior to her terminal illness I hadn’t seen her in three years. This is incomprehensible to most people, and I tend to evade that information, lest I be viewed as a monster, a stranger, an outsider, a foreigner in the land of familial relationships.

In the eleventh grade I read Camus’ L’etranger in French class. The narrator, Meursault, attends his mother’s funeral, where he doesn’t cry. Much is made of this detail—later in the text, when he is put on trial for murder, it becomes the clinching evidence against him. He is found guilty of the crime not because he committed it, but because he didn’t cry at his own mother’s funeral. My French 4 class acted out the courtroom scene of L’etranger for French 3, who acted as the jury. I was cast as Meursault, and was found as guilty as my textual counterpart. Even in the moment of performance I felt the weight of the hypothetical guilty verdict.

At the Art Institute that December Friday, I was distracted, but so was everyone else because of the impending holiday party. I helped decorate the office, hanging ornaments from fixtures and fixing strings of lights onto the walls. The party itself was held in the Stock Exchange room, designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler, which had been dismantled and reconstructed piece by piece in the Art Institute after the original Chicago Stock Exchange was demolished. It’s a beautiful room, with ornate wallpaper and woodwork, and two blackboards labeled “New York Stock Exchange Quotations,” and “Chicago Stock Exchange Quotations” where changes in the market were hand written in chalk by clerks who stood on wooden ladders that look perilously flimsy in archival photographs. There was a hot buffet set up for the party, free flowing wine, and a dessert station. A DJ played party music, and some people had dressed up for the occasion.

I got a plate and found a seat at a table. I looked around the room and considered what I was seeing on Mom’s last day on earth. She would have loved it: the fact that it was taking place at the Art Institute, the display of food and wine, the formality. I realized that I was eating the last meal that any of us: my mom, my sister, or I would have before she died. I thought of it as a kind of celebration—that on her last night on earth I was here in this beautiful room, with this beautiful food; that the next time I walked into the Stock Exchange room I would no longer have a mother. I raised my glass and silently made a toast to her. I didn’t talk much, but the music was too loud for all but the closest conversation, and the party was kept on a strict deadline: everyone had to be out of the building by seven.

When I left the party it had begun to snow slowly, cinematically. I stopped to take a photo of the north-facing lion on the Art Institute steps, draped in a wreath and gaining an ever thickening coat of snow. I took the train home and went to bed.

At 2:00 a.m. my sister called, and I woke up instantly. Mom was in her last hours, my sister at her bedside with Mary, who’d been living at Mom’s condo since August. I moved from the bed to the couch, where my cat splayed herself on my legs, providing more comfort than she knew. I fell asleep and a couple hours later my phone rang, waking me instantly once more. It was my sister, calling to tell me that she’d passed, it was over. “Okay,” I said. This moment had been coming for months, but I couldn’t think of anything else to say. “Okay, okay,” I repeated, until the call ended.

When my husband woke, I got off the couch to tell him, but my voice was small with sleep and he didn’t hear me the first time I tried to say it. “My mom . . .” I said in a whisper, “mom . . . mom died,” I said, the last word getting stuck in my mouth. I could tell he hadn’t heard me, and waited for a moment before trying to say it again. “Mom died,” I managed to say, my voice so small he had to stand right in front of me to catch it. He hugged me and I allowed myself to be held.

While I’d been grieving privately at work, I’d been grieving publicly on social media. It felt safer to grieve there; I could reveal as much or as little as I wanted, I never had to see the reaction in anyone’s face, and I could turn away from it at any point and get lost in work, TV, or household chores. I made regular posts on Facebook and Instagram about my travels to Boston, funny things Mom had told me during those visits, and old photos that had surfaced. I turned to social media now. I posted a photo of Mom from the mid-70s and a short message about her passing.

I am my mother’s daughter, there’s no escaping that. My body came from hers, it is elemental and undeniable. Like it or not I am a living testament to her. After she died, I was able to remember the good things she gave me, notably a love of words and language and a reverence for the magic of writing—the trick of creating something that didn’t exist before simply by writing it down.

I didn’t cry when I got the call, I didn’t cry when I told my husband, and as it turned out I didn’t cry at her memorial. But I did cry when people responded to my post about her passing on social media. I felt safe curled up under my bedsheets in the dark, the only light coming from my phone screen as I absorbed people’s messages of support and condolence. It wasn’t a big cry, no gulping heaves, no uncontrollable sobbing, but as I read people’s responses from the privacy of my bedroom, tears spilled over the corners of my eyes and made their way down my face. Then I’d turn off my phone and they’d stop, and when I checked social media again and saw more responses, they’d begin anew.

J.H. Palmer lives in Chicago. Her work has appeared in Belt Magazine, The Toast, Story Club Magazine, Thread, and Chicago Story Press.

SPOT IMAGE CREATED BY WARINGA HUNJA

HMS is an arts & culture nonprofit (Hypertext Magazine & Studio) with two programs: HMS empowers adults by teaching creative writing techniques; HMS’ independent press amplifies emerging and established writers’ work by giving their words a visible home. Buy a lit journal (or two) in our online store and/or consider donating.