Recently, I was invited to perform a reading of The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, the book created by Pulitzer Prize-winner Nikole Hannah-Jones as an expansion of the essays presented in the New York Times Magazine. My assigned passage was the history of Celia, an enslaved girl who, at age fourteen, was purchased by a Missouri farmer for sex. After five years of enduring rape and now sick and pregnant with the enslaver’s child, Celia begged him to stop and warned that she would defend herself the next time. When the farmer attacked her yet again, she fought back and ended up killing him.

Missouri law stated that women could defend themselves against “every person who shall take any woman, unlawfully, against her will . . .” (cited by Roberts, page 541). But the court ruled that Celia was not “any woman.” She was chattel property and therefore had no legal right to defend herself. In 1855, Celia was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang. Yet her hanging was delayed until after she gave birth—the child would become part of the dead man’s estate, after all. The baby, however, was stillborn.

I was sitting with this history for months. My studies of Celia were punctuated by grief for this enslaved woman-child who lost the battle against the powers that controlled her life. She must have been terrified, but she bravely took the only action she could to protect herself and her unborn child. She suffered death as a result. Had this horror happened in the Caribbean—Jamaica—rather than Missouri, Celia could have been an ancestor of mine. I cried for her.

Reading Celia’s story exhumed a long-ago, painful experience of my own and made me consider the challenges of a mother trying to shield her child from a malevolent world.

*

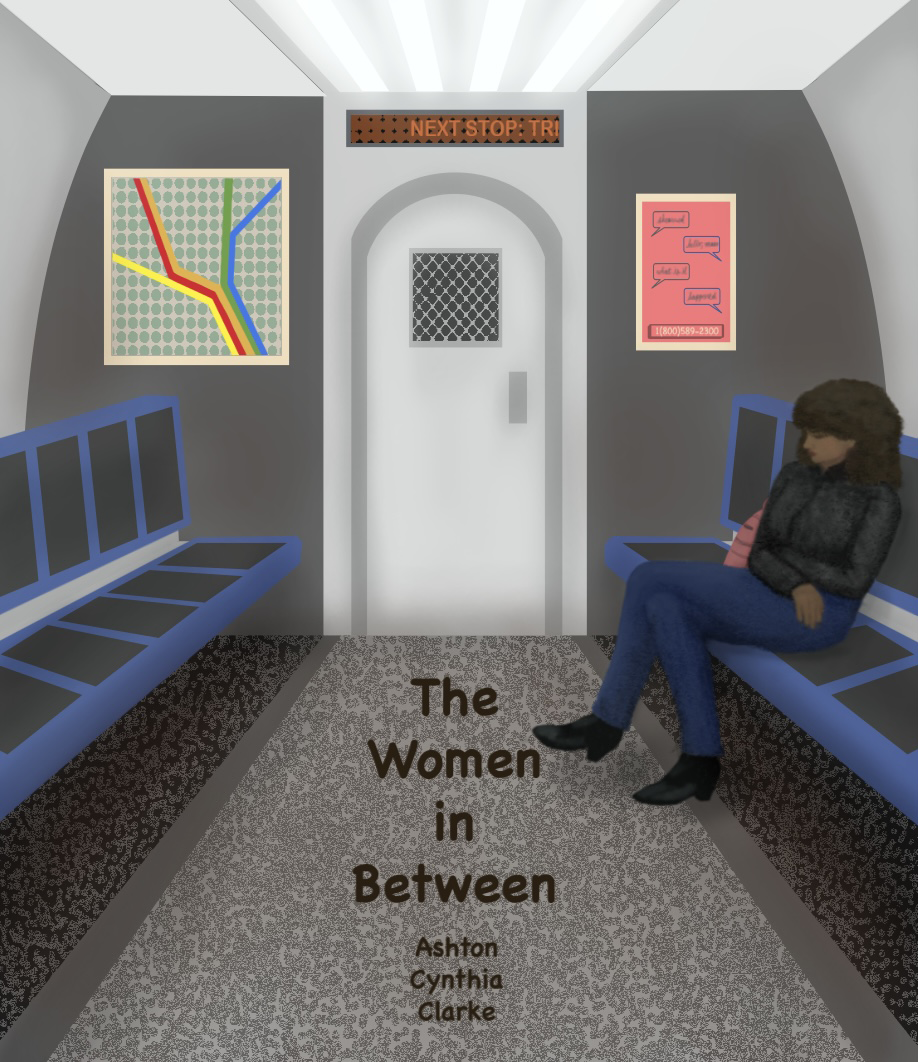

Back in the mid-1960s, when I was a young colored girl, riding the crowded New York City subway was something my mother and I endured on the regular. If whatever we needed was not sold at the local A&P Foods or Five and Dime, it meant leaving our Upper West Side neighborhood, a few miles from Harlem. We’d take a twenty-minute train ride, seven stops downtown in the underground tunnel of the Number 1 train to Korvette’s Department Store. Or, uptown thirty minutes on the 2 Express to Alexander’s. My mom decided our

route according to whichever store was having a sale.

On this latest shopping trip, Mommy and I were lucky to find spots next to each other at one of the vertical poles that went floor to ceiling in the packed subway car. The alternative, clutching cold straps dangling above seated passengers, would have been impossible for me at eleven years old.

I felt sorry for the people who were “straphanging.” They pressed knees against the person sitting in front of them in the red, fake leather seats, stained and ripped in places. Each time the train lurched to a stop or careened around a curve, I glanced around, ready to snicker if someone lost their balance and ended up nose-to-nose in the lap of a seated passenger!

It was icy winter outdoors, so I bet most people welcomed the heated subway car. Not me. It was the beginning of the dreaded 5:00 p.m. rush hour, when it seemed there were more people on board than the train could safely carry. Add to that, everyone’s bulky, cold weather clothing, briefcases, and shopping bags, and I was squished against other passengers whose coats smelled of sweat and damp wool. The hot train seemed to steam its own dirty floors, wet with melted ice from hundreds of pairs of winter boots. It felt like the windowless bathroom of my parents’ apartment, muggy after the morning baths of four family members.

I hated my year-old red, corduroy jacket with beige piping and just wanted to rip it off. It made my round body look like the bursting skin on an overripe pomegranate. That’s why we’d gone shopping in the first place. But my new coat was in one of our bags, instead of on me where it belonged.

A salty drip of sweat stung my eye, but I still managed to peer through the graffitied windows. White spray paint declared names of the creators—names like TAKI and Papo. We were riding the “Express” train, so there were only four stops between the shopping center and my neighborhood. Each time the doors slid open, I turned my face to claim any cold draft that might whoosh in from the station platform.

Music from a nearby transistor radio made its presence known. I could make out Frankie Valli’s falsetto, straining high above conversations of passengers and clack-clacking of the train against the tracks. There was a tall man right opposite me, his hand that I could see was gripping the same metal pole that secured me and Mommy. He was tall and skinny, with pale eyes and a skinny blond mustache, too. His brown hat flipped up in the front, like Yogi Bear’s in the cartoons. He swayed in time with the rocking of the train and the music; soon I did, too.

I was suddenly super-aware of my brown, double-knit leggings, which had also gotten too small, too fast. They overheated and itched every turn on my body, digging into places that I wanted to ignore.

More itchy than usual.

The train went dark for a second. It did that sometimes, the lights flashing off then on.

That’s when I noticed the man in the hat was grinning at me.

Was it shock that made me just freeze when I felt fingers creep across my inner thigh then begin to scratch at my privates over my leggings?

Was I too afraid of accusing the wrong man? It could be an easy mistake to make. People were crammed tight around me. And I didn’t have the nerve to look down to identify the snaky fingers. Or look up to challenge his eyes.

I felt sick, disgusted. No, disgusting. No, I didn’t understand what I was feeling.

And even though I was trying not to look, I could tell that he was continuing to grin nastily as he touched . . . But I just stood there, motionless and mute.

Suddenly without a word, Mommy threw her small body between me and the man’s hand. She must have just spotted his long, whitish fingers creep- creeping. Her shopping bags crackled and crunched, asserting rage to accompany Mommy’s silent action. At the same time, the train squealed to a stop and people shoved to escape through opening doors. The man in the hat was the first one out.

“Are you alright?” Mommy whispered. She looked as if she was in pain. I nodded a silent yes.

We never spoke another word about it.

*

Why would the horrid secret of that train ride have to surface then, when I was reading, studying, rehearsing for a performance?

I began hating my child self for being so stupid in that subway car, too confused to scream, too afraid to protect myself. I somehow felt as if I was responsible, like I was part of the crime.

But at times I also blamed my mother. “Mommy, why didn’t you notice the groper sooner? And why didn’t you talk with me about it later?”

As that memory on the train played in my head, I grew angry at my deceased mother and could only dwell on what I considered her failings back then. But what I realized was the more I read about Celia, the more truths I discovered about my mother, and I began to reframe how I saw her.

In her silent, deliberate action on that train, didn’t my mother also deliver her own body to protect me? She, too, was probably afraid. It was 110 years after Celia’s execution, but Mommy was also a colored woman engaged in brave battle against a white, male molester. She summoned her strength to shield me, her child, just as Celia had. I cried now for my Mommy, ashamed that I had ever blamed her. “Mommy, I love you so much for what I now understand was your bravery.”

With this realization, I closed my copy of The 1619 Project. I was ready to channel the story of Celia, which was the story of my mother and the stories of all the women who would lay down their own flesh and spirits between their children and an abusive world.

1 Roberts, Dorothy. “Race.” The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. Created by Nikole Hannah-Jones and The New York Times Magazine. First Edition, New York: One World, 2021, p. 53-54.

Ashton Cynthia Clarke is an African American/Afro-Caribbean, Los Angeles- based writer and storyteller. She has performed her true, personal stories on stages throughout the L.A. area, in her hometown New York City, and virtually. She has work published online and in print, including The Storytelling Bistro: Stories, Poems, and Reflections; The Academy of the Heart and Mind; These Black Bodies Are; and Olney Magazine. Much of her work references her Caribbean ancestry. Ashton developed an animated short based on a family member’s life in Jamaica, Titta and the Mango, which you may enjoy on her YouTube channel. In her writing, Ashton aims to present universal sentiments that will transport her audiences along with her. She dreams of connecting to ancestors and other beloveds through ties that transcend this plane.

Instagram: @ashton.c.clarke

Hypertext Magazine and Studio (HMS) publishes original, brave, and striking narratives of historically marginalized, emerging, and established writers online and in print. HMS empowers Chicago-area adults by teaching writing workshops that spark curiosity, empower creative expression, and promote self-advocacy. By welcoming a diversity of voices and communities, HMS celebrates the transformative power of story and inclusion.

We have earned a Platinum rating from Candid and are incredibly grateful to receive partial funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, Illinois Humanities, Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, and Illinois Arts Council.

If independent publishing is important to you, PLEASE DONATE.