We take the Subte two stops on the blue line and ascend on foot through San Telmo, the cobblestone streets. The moon reflects our footsteps on each brick. It is beautiful in the way only a picture can be. Beautiful in the way life is when viewed from afar, illumined, and sometimes even framed.

This is not a photograph.

I am here and she is here, and we are here, walking, hand-in-hand through La Manzana de las Luces. Train whistles in the distance. Her hand inside mine. She pulls me closer and I surrender: we move along, one body floating through the night.

This morning was A Walk in the Park, but I could hardly concentrate. I was thinking about her. She who is so close to me. I was thinking about Isabella. She turns her head, as if she can hear my thoughts, as if she can hear me speaking her name in silence.

She pulls me further and we descend.

“We have to go down,” she says, laughing, her voice slipping through me. “Everything is connected by a series of underground tunnels.”

“Everything, but everything,” she continues, breathless, “is connected.”

In English, her voice sounds staccato. Stopping and starting, italicized at the most unexpected moments. English with an English accent. A sense of urgency.

I am panting alongside as we pause, breathless and still trying to breathe inside each other’s mouths. The air is damp, wonderful, moist, heavy with the smell of rain, a passing storm or a storm that’s passed, but the sea is calm tonight. The sea is calm to-night. The sea is calm to-night …

I search for the first verse. The second line. When I am nervous, I recite poetry in my head. Arnold, Eliot, Cummings, Marvell, Rilke. Sometimes even Ovid. All of my favorites. But I am too nervous, too nervous to recall anything but this moment, trying to capture it before it

passes, too.

I have been here for three days. Dining on bife de chorizo and morcilla in between a billboard for Bolivia and a Deberser look-book—or maybe the other way around—Dave Goldstein following me for all of it. Except Dave Goldstein isn’t here now. And what a pity. For him, not for me. I’d rather remember Isabella from memory. I’d rather forget everything else.

What else is left?

Next week I will be doing the same thing, but in a different place. The same thing. But without her.

We move past Plaza Dorrego. A dozen vacant café tables and signs pointing nowhere. The party has been packed up, gone until next week. I know because I’ve seen pictures. Metal trinkets, leather belts, necklaces: antiquities. Remainders of the day. I feel the sweat on her palms, the heat of her skin. The earth moving under our feet.

And what would Ana say to me now, if she were here? What would my mother say if she were still alive?

“A mist all the scams and backstabbing, and all of those false promises, and no one to trust, and so many horror stories … a mist all of it, you have gotten on so well. And I am so proud …”

And maybe I would realize—or maybe I wouldn’t—that what she was saying was everything was a mist; everything and all of it, a thin film of reality, cupped and suctioned like a contact lens in each eye, and it had become impossible for me to see beyond the haze. And yet I had to try. And yet I was trying now.

I try to picture it again.

All I remembered from this morning was Isabella, her enormous eyes, her slender nose and round lips. Isabella who was not in the park, who was not in Belgrano at all. But she was there all the same, a projection in my mind, there as I stood silent, filmed or not filmed—I never know when the camera is rolling, I only know there is more than one, and if one isn’t on, another one is—there as I wondered what had happened to my life, wondered where all of it went. Except I know, at least, that answer.

All of life is misunderstanding, miscommunication. Contact cut just when the moment becomes possible. A look in the street, a handshake, sometimes even a hug. All the familiar signals, everything reduced to formalities. Like walking on eggshells. We turn away from ourselves. We turn inward. It’s as easy as putting on a pair of slippers. Going to the movies, going to the bar, holding hands, holding hands but never touching, a nod of the head, a hello, gestures of salutation or farewell, graceful contacts … contacts? Message-as-massage, well-wrought conversation … an excuse me or pardon or no problem (what ever was the problem?) or sorry, do you have … (always apologizing but for what, I never knew) please, don’t mention it … a high-five at a Mets game, a day at the races, a shrug, a wave, a seat given or taken on the R train, an outstretched hand on the cool pole. We shut up just when we should say something, just when words could have some use. As easy as putting on a pair of slippers. Two lips moving. An outstretched hand …

You came to me. Touched me. Entered me. I saw with your own eyes.

This passage is addressed to me, but it is written for you.

Will you find it someday, months or years later? Will you find it, read it? Will you know me?—not the apparition but the person, or rather—the soul? Can anyone?

We slip into Iglesia Nuestra Señora de Belén and I lose myself in a maze of pews, concave domes and grooves, nooks, cupolas, everything painted white except for the stained-glass windows. An opaque reflection.

I often have these fainting spells. In bars, hotel lobbies, concert halls. In the passenger seat of a cruising taxi, doing fifty, maybe sixty, hands and head out the half-held sliding translucence. Flickering black spots weave in and out of focus like cue marks in an old film. Imperfections of reality. My soul contracts until my body crumples to the floor. I never remember anything else. Is it jet lag? Is it euphoria? Is it my body, every fiber and neuron, and each cell exasperated; is my body giving up?

Either I suck in life too fast, or too much, or too often. Or life sucks me dry. A hiccup in the vacuum of eternity. I am choking.

Every time I come back, I’m a little bit less.

Every time I come back, pieces of me get chipped away.

What is left?

A child’s room: four walls devastated by time. Scotch-taped boxes. An empty valise. Things I will never remember, or never sift through, or never see. Things that have been lost for good. For good or bad, but for good.

My petrified smile.

Isabella finds me ten minutes later—maybe fifteen—neither of us wear a watch.

“What were you doing,” she asks, “staring at the window?”

“Checking myself out,” I say.

We laugh. Or rather, she does. We exit through the side doors left ajar, aged wood creaking, air rushing in as we rush out.

I don’t tell her what she doesn’t know, what she could never guess. I don’t tell her I am just checking my self out.

Making sure I am still here.

Time Again

They watched him from a park bench. From the center of Barrancas de Belgrano, the breeze coming in from the Río de la Plata—or an automated fan.

From the sun streaking through at seventy-six degrees, the angle of the moment passing.

From a reclining position, legs shifting, lips wet, cigarettes dangling from the corners of their mouths like lollipops. Sucking sounds. Smoke blowing through the trees: pines and Jacarandas, and an enormous Ombu at the center. Cars shrinking to a halt on the corner of Arribeños. Laughter. Film rolling. They watched. Time and time again.

He came closer, emerging from the dog run, and they collectively sighed. It was all very audible amid the noise of afternoon. A boom mic hanging from every branch.

“Is he giving them dégagé?”

“Is he giving them onda?”

And when they said, “them,” they meant, “us.”

They weren’t sure what he was giving, but they were taking it. They took it in three-quarters and in profile, in close-crop and in tracking shot, and from their personal mobiles too, streaming a sequence of indefinitely proceeding images that could eventually, in days or weeks—or maybe hours—form a coherent narrative.

We hear the breeze pick up from the bay, audible whistles and the shrill sound of brakes as you come into view: a look of inconsolable sadness STOP enter camera left, with a stronger gait, the sun enveloping your eyes as you enter across and STOP descend through the dog walk on foot, bending and leaning here and there, perhaps petting a pooch if time allows but always moving STOP hands in pocket, craning neck, in search of something but still smiling

STOP

A narrative copied and cut, transmitted via telegram. Piece-mail.

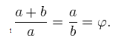

Actually, he emerged through the shade of a pine and paused mid-stride at the wrought-iron gazebo, as if uncertain, suddenly reluctant to proceed, oval eyes enlarged unnaturally, according to the law of divine proportion.[1]

He was smiling.

Standing—“con la lengua en la mejilla,” someone uttered—legs taut, as if he were ready to spring into action, sprint through the curving pathway that led to the river. As if he were ready to escape. A forearm came into view, veiny and robust in the plummeting perspective.

“Now THAT’s a figure of speech, darling.”

Voices. Passersby. An audience. The hush of silence. La Glorieta at noon.

But he did nothing, but nothing. He stood there, smiled, one hand in his jeans pocket, the other running through his wavy hair, blond strands flowing in and out of his eyes; in and out and in and out of focus, standing expertly and absently, like a mannequin. A bust at the Barrancas de Belgrano scaled to size, a statue of limitations. And a few yards away, the Statue of Liberty in miniature.

The Director entered along that nine-foot replica, camera right, under the unwavering torch, shaking his head, pursing his lips, running his hand over his head (he was bald), muttering stage directions, spitting into the wind, asking Chris Selden if he could be more natural. And lose the shirt completely. Please—

Give me something masculine … Details which said more about the Director than they did about the subject.

“Is this the breathing version?”

“Is this the real thing?”

He could feel the words crawling all around him and under him and past his unblinking eyes like ants.

A voice-over drowned out the rest.[2] The agents, the publicists, the journalists. Squawking in the background, hawking their wares: each part partitioned to meet the current need, and then redistributed. Taking a cue from Satan, their greatest strategy was to make the world believe Chris Selden didn’t exist.

Humility is a trait that can only come from its root word, or origin: Humiliation. And such is the case in this book and the one following, and especially, in the one that came before. Chris often felt that he was traversing a world that had as its soundtrack “A Dancing Shell” by Wild Nothing—only one song, played without pause until it began again—walking along the streets while the verse “I sold myself for a shot at the moon … I sold myself so I could be a big star … And I’ll be your monkey, every night, if it makes you love me, watch me now. Watch me, watch me …” rang through his ears.

He’d do everything they’d ask him to. Within reason, but reason was another word that has its origins elsewhere. Underneath it all, the power of comprehending, the rational ground or motive, the exercise of the mind … all of these definitions can best be explained by a treatment that affords satisfaction.

Walking along the streets with his camera eye and his mask in place, with the secret knowledge that he was not who he was to the world, or rather, that he was more than what the role called for, more, even, than what comprised the whole play; this was a satisfaction in itself.

It was the greatest one.

A few extras pushed a piano across the dirt. Violin, double bass, a bandoneón. Tango sounds. A cloud appeared, expanded across the sky.

The lighting changed.

They watched it all unfold, simultaneously seeing and shooting, and dreaming, too, dreaming until they couldn’t stand it any longer, couldn’t stand, couldn’t sit. Their hands fumbled for an opening between buttons, ran down their navels, found their way to their crotches, clasping their inner thighs until they cupped their groins, rubbing vigorously through their jeans, unzipped in fleeting moments, fingertips reaching back toward each vent, opening up and unfolding, feeling the heat, and the flow, and especially, the longing. Beating around the bush.

They took turns until the scene faded out.

Una Vez Más

“Repita eso, por favor.”

I start. Stop. Sputter out more Spanish mixed with English. I only want to order another Malbec. Malbec from Mendoza. I try pointing to a photo of a llama hanging from the wall behind the bar, a llama that looks like the one on the cylinder’s seal, smiling with its big, buck teeth, inflated further to reach around the bottle, but I mispronounce that, too. Yame? Lama? All I get is raised eyebrows and curled lips.

My parents never taught me Spanish when I was a child. Instead they each spoke English with indelible accents. I got fucked. I can’t speak Spanish right, I can’t speak English right. My parents’ accents ruined any chance I had of speaking properly.

So instead I just speak.

Outside, the earth changes color, from royal blue to purple. Three clouds in their slow procession across time. The moribund sun.

When I finally receive my glass of wine, it’s white, from Mendoza. A Torrontés. I smile and take a sip anyway, turning my attention to my notebook.

What is left?

I had been writing. Writing and re-writing. I try to write Going Down again, this time in eight pages. It takes me nine minutes. I make a note to play it during intermission.

Why always this desire to repeat?

My thoughts drift to last night. To yesterday morning. They drift until I am thinking about my past life. I rewind.

There were no Cubans in Oradell. Hardly any Latinos at all. My popularity in high school depended on it. I was a novelty. The blond-haired Cuban who turned brown in summer. I had the feeling friends invited me over just to show me off.

Look! And he speaks English!

But please, Mom—can we KEEP him? At least till dinner?

I often wondered why my parents moved there in the first place; was it, after all, a performance? Were we masquerading as The Whites—the new Genet being staged in Bergen County?—and if we were, I never got the script.

I picked up comedy instead. I played Class Clown. For a while, I forgot I was any different from anyone else.

For a while.

I think of numbers. Situations. The arrangement of events that form a life. It has been one year and ten months. That’s 670 days since I walked into J&P Talent, into its dilapidated office: the lobby and everything else. I never walked back out.

I have traveled the world.

I’d like to think I learned things, soaked them up like a sponge—an old nickname at OPS—discovered something about life. If I learned anything, it is that I don’t know a damn thing. I am here to be taught.

Everything is passing. And everything passes me by.

I caress a shiny, copper lighter: two figures locked in a thrilling tango stare-off. A parting gift from Isabella. Something to remember her by.

A memory.

I’ll caress it again, and again. Finger it. Watch the flame flicker. Maybe I’ll remember her each time. And maybe each time it will be different.

“Drone On” by Physical Therapy begins to blare on the bar’s speakers.

“What do you see when you see me?”

Glasses clink. People I’ve never seen before sing along.

“You’re alive, you’re alive … You’re alive now … I see you again …”

It’s my last night in Buenos Aires, I murmur, sipping slowly, tasting the saccharine at the back of my throat. And I am alone. I look around. Maybe I look like a mannequin. So used to people looking that if they stopped, if they shut their eyes, if they didn’t look, I’d feel as if I wasn’t there. As if I am not here.

I glance at a watch that isn’t there and wonder when Dave will arrive; one final ride, cruising along the Río de la Plata until the first light of dawn, and for a second, everyone and everything freezes mid-frame, lips open, eyes half-shut, and everything is silent except for the drizzle, the pitter-patter of rain against windowpanes—a sound effect played on a loop—and then the second comes to an end. Another one begins.

I see you again

Repeated indefinitely.

I like music so much because it is liminal. Temporal. Three minutes. Four? Sudden illumination, I think. And with a countdown. I like music so much I let it bleed across the pages, too. I look at the camera. I look right at you.

“I know you want, I know you want. I know you want, I know …”

“I am listening to the same song you are,” I say.

I have a habit of breaking the fourth wall, and now the whole structure collapses. Outside, the pale light illumines each brick. A puddle reflects the shimmering sky

and then dissolves.

Dave appears outside, motions to me, dangles a set of keys. I leave four pesos on the counter.

“How do I look?” I ask as I slide in, recline the seat.

The convertible turns. The panorama of Puerto Madero opens up, unfolds, surrounds me.

“Same as ever,” Dave says.

“Same as ever?”

He nods, shifts the stick into sixth-gear. I want to ask where he learned to drive like that. I want to ask, from which movie. Instead I ask him how I look. A third time. Staring at my darting reflection at fifty, maybe sixty miles per hour. And repeating, repeating …

Fast-forward through warehouses and high-rises, the hum of the engine. Ripping wind. Boats at anchor in a freeze-frame: River of Silver. Something like torque shoots through me. The dimensions expand until they explode.

“Same as ever.”

But I only realize later.

He means it as a compliment.

[1]  Also called: the golden ratio.

Also called: the golden ratio.

[2] He was unable to create that true sense of identity and livelihood that must go hand in hand in order not merely to exist, but to survive. That love every artist feels for his work was absent, because the artist himself could not identify with his creation, which was himself. He hadn’t yet realized that he would have to destroy the portrait and begin again, not by using blood or pastel, but words, the beautiful range of sound and sensation available to us no matter our language.

Chris Campanioni’s new book is Death of Art (C&R Press). His “Billboards” poem responding to Latino stereotypes and mutable—and often muted—identity in the fashion world was awarded an Academy of American Poets Prize and his novel Going Down was selected as Best First Book at the 2014 International Latino Book Awards. He edits PANK, At Large and Tupelo Quarterly and lives in Brooklyn, where he teaches literature and creative writing at Pace University and Baruch College.