Interview by Jael Montellano

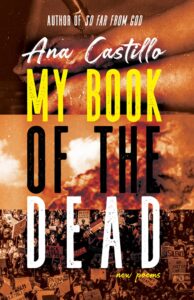

There is something about Ana Castillo’s latest poetry collection, My Book of the Dead, that has the quality of being woven. I imagine this mythic feat as elemental, threads stretched over the heddles and beams of a loom as the artist methodically works tender fingers to entwine this complex masterwork like wall tapestries of old, luxurious in detail but just as impressive in span and width, in chronicling pasts that might be lost to the excess of the endless news cycle, colonialism, capitalism, and more.

Castillo, a double-recipient of the Lambda Literary Award for Bisexual Nonfiction and Fiction each, and recipient of Columbia Foundation’s American Book Award, is known for her varied novels, poetry and essays, and is no stranger to bearing witness to history, having come of age in Chicago in the 1960s.

In My Book of the Dead, Castillo assembles the realities, liminalities, and waking nightmares of our present day. In anticipation of its release, we correspond to talk about her collection.

My Book of the Dead spans the immense events of recent years; the epidemic of gun violence, the tumult of the Trump presidency and its fascist flirtings, the catastrophes of climate change, and personal losses during our present pandemic. Tell me about the process. Did you find it challenging to organize the poems into their three-part structure, given all the turbulence of the events you were chronicling?

I decided to start a new collection of poems maybe as far back as 2012. Since poetry is a slow process for me sometimes, I projected it might take as long as a decade to have a book. In 2018, I decided to put it together. As you say, the poems cover a wide range of topics. Since I work alone, I decided how to organize poems that, yes, addressed my ‘witness’ of recent times. I remember the day I worked on the three sections, working old-school with hard copies, spreading them out on the bed in a small apartment in the Bronx. I’ve worked as both editor, writing teacher, and writer of most genres for about half a century now, so all I can say is that some of these steps come as second nature to me. I submitted the manuscript to the press for consideration the way the book is at present.

Your collection holds varied beloved artistic references; from echoes of Hieronymous Bosch’s Dutch Renaissance to Mexican artists like Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and other surrealists. What connection do you draw to these (or other) fine artists and what is meaningful about their work to you?

My bachelor’s degree is in art. While art was my first love, I left it while I was still an undergraduate to dedicate myself to writing poetry. Nevertheless, the earlier 20th century artists (and writers) remain a great influence on me. A few of my line drawings appear in this new collection.

My bachelor’s degree is in art. While art was my first love, I left it while I was still an undergraduate to dedicate myself to writing poetry. Nevertheless, the earlier 20th century artists (and writers) remain a great influence on me. A few of my line drawings appear in this new collection.

Most writers and artists don’t like to admit their influences, but of course, those we admire, read, and look at time and again are our teachers. I think My Book of the Dead in many ways reflects what I admire and seek to produce in my own work, though I wasn’t trying to emulate any particular one. But anyone who says the artists and writers they study don’t influence them, directly or unconsciously, isn’t being honest.

You are a granddaughter of immigrants. You write in English and Spanish, and sometimes Spanglish. Do you decide on a singular language for a particular poem, or do the poems come clothed? How do you make these linguistic choices?

I am identified as Chicana. My [paternal] grandparents were Mexican; my father was born in Chicago. The woman who raised him migrated with her children to Chicago around the time of the Mexican Revolution before Border Patrol was established. My mother was born in the States to Mexican parents in the 1920s. My [maternal] grandfather was a signal man with the railroads. In 1929, the family was repatriated, where my mother then grew up in Mexico City. U.S. aggression and greater power over the course of history has always used its advantage over Mexican labor, so my family history is more of a migratory ‘transnational’ one.

My generation preceded the concept of “bilingual education” and advocated for it. I was a child in public school before the Civil Rights movement. Spanish wasn’t allowed to be spoken on school grounds and within the job. At home, my mother and paternal grandmother spoke only Spanish. My father was bilingual. My older siblings, born on the border, spoke Spanish as a first language and learned English in school. Because of the prohibition and stigma of speaking Spanish, they lost much of their first language.

When I started public school, English was a second language. Later, when I decided to become a poet, I was also a grassroots activist and chose to use English because other Chicano/as (Latino/as) had been taught to read only in English, although we were bilingual. As a political strategy, I used some Spanish because that was our daily spoken ‘language.’ In the 80s, academics began to study this phenomenon in the U.S. and called it ‘code switching.’

In my daily life, I speak Spanish. I could write a poem in either language, but as I live in the United States and publish here and very significantly, am Chicana, I choose English most of the time. I included a handful of poems in Spanish and made certain I provided English translations before submitting the book to a press.

As a bilingual writer myself, I frequently struggle with deciding what (and even if) to explain to white audiences and what to reserve para nosotras. This collection is full of proud Native, Aztec, and Mayan references. How do you navigate references a white audience isn’t familiar with? How do you decide on translation, in whole or in part, with respect to a white audience?

My beginnings as a ‘protest poet’ not only directed my writing to other like-minded political people, but for a very long time, my work and the work of many of my Chicano/a, Latino/a peers was only received by other Latino/as. The ‘crossover’ of my work came with my third published novel, So Far From God, and after the first edition of my poetry collection, My Father Was a Toltec.

My novel So Far From God is based in Northern New Mexico. The state was annexed in 1912. Spanish was not only a long part of its history, according to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Spanish is in fact an official language. W.W. Norton respected that and didn’t italicize any of the words that were used in speech by New Mexicans.

We think that language is only an aesthetic choice or a matter of personal expression, but for Mexicans and the people in the U.S. who share that history, suppression of our culture is political. This is the reason I choose the language/s I choose, and when.

I’ve never written for a white audience. As a woman from the margins of mainstream society, it’s critical for me to give voice to my experience. In a few instances, I’ve been accused of pandering to a white mainstream audience exactly on the basis of how Chicano/a my writing may be, like So Far From God. My outspoken politics confirm otherwise. But one would have to assume that there’s a notable white audience out there that wants to have us talk about ourselves in stereotypes. The Anglo/White literary society has long shown that they prefer to hear about minorities, including all women, from white male heteronormative writers. The value of the writing of any other is always scrutinized in this country. In the last half century, an exception has been made, I think, with men of color and POC from other countries.

With code switching, there are debates on all sides. One is the academic proposal that writing in both languages or using colloquialisms ‘degenerates’ the language. Without getting too far off the question of my own choices, I’ll say that the speech a community uses to communicate legitimizes that language.

In these times I don’t assume that mainstream audiences, to whatever degree my work may draw people outside of my immediate ethnic U.S. culture, don’t understand Spanish or any of the pre-Conquest references. One of the poems in the book was translated by Tyehimba Jess, an African American Pulitzer Prize poet studying Spanish. We can’t assume who speaks what language in these times.

Regarding Pre-Hispanic references, I can’t assume anyone is familiar with them. In school, we don’t study the contributions of the Toltecs or the people we know as the Aztecs. We are battling particularly repressive times where there is further suppression of the experiences of POC in this country.

The short answer is that I continue with the agenda I had as a girl, writing to fill in the blanks, spaces, silences and outright lies regarding POC, specifically Latino/a/Chicana/os/Chicanx when and how I am able to do so. I combined this desire with my own creative ambitions; in this book it is free-form verse.

One of your speculative poems, “By the End of the Twenty-First Century When,” imagines Evangelicals visiting Mars searching for heaven while Mexicans “stayed / (or were left behind)” on Earth. The resulting picture is of a “glistening city on swamp / one chiseled stone at a time.” Firstly, I adore this poem; secondly, I longed to ask you whether this is the vision you wish for colonized peoples. To rebuild their temples, either physically or metaphorically?

Thank you! Often, but not always, I enjoy letting “flight of fantasy,” and stream of consciousness lead into a piece of work. This, I believe, may be part of the process when we think of poets as seers and prophets.

Over a quarter of a century ago, I wrote in So Far From God about the day dead birds were falling from the sky in the context of climate change. This took place ‘mysteriously’ in 2020, in Southern Mexico, where I reside.

The poem, however, isn’t meant as my wish or prediction. As with the dead bird reference, it may be considered as a possibility. The poem does make references to many of the extraordinary contributions of people throughout the world and how they are returned and valued.

In the titular (and my favorite) poem of the collection, which appears at the end of Part III, you, the narrator, make this arduous journey to Xibalba and are returned due to unfinished labor. ‘“You have much to do,” he-she directed.’ What do you, a Rainmaker, activist, and lifelong renegade, see as this unfinished labor within your life?

2020 was a monumental year of crisis for the world. It affected every individual on the planet. For many, including myself, it also brought losses of human life, even while major leaders raped the planet and pillaged. On a positive note, the pandemic slowed down travel and some natural resources began to revive. Without being too dramatic, I think most of us that are surviving this year feel a little like the survivors of a kind of real wakeup call regarding a possible Armageddon, but we aren’t out of the woods yet.

On a personal level, somehow I have also ‘returned,’ like the tree in the forest we thought was dead—due to age, disease, appearance of inertia, isolation or abandonment—and turned out to be dormant. While my own energies may no longer be what they were, I am here and also, appreciate and admire the new generations of activists these global challenges have brought forth.

I made a commitment a half century ago to make my writing my own tool and weapon to fight injustices as I recognized them, and this continues. I am grateful to the gods for it.

Ana Castillo is a celebrated author of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and drama. Among her award winning books are So Far from God: A Novel; The Mixquiahuala Letters; Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me; The Guardians: A Novel; Peel My Love Like an Onion: A Novel; Sapogonia; and Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma. Born and raised in Chicago, Castillo resides in southern New Mexico.

Raised in Mexico City and the Midwest United States, Jael Montellano is a writer and editor based in Chicago. Her fiction, exploring horror and queer life, features or is forthcoming in The Selkie, the Columbia Journal, Hypertext Magazine, Camera Obscura Journal, among others. She holds a BA in Fiction Writing from Columbia College Chicago. Find her on Twitter @gathcreator.